Do businesses fully understand the level of threat from modern terrorist groups or insurgents?

Certain sectors of business understand it, like the oil companies. They’ve been at the sharp end of this for a long, long time. In places like Algeria, Libya, even in Saudi Arabia, oil installations and oil platforms have been attacked. Every time there is an attack, these companies employ more security. In Iraq, where I worked for many years, there’s heavy security on the oil fields. And it costs big money, hundreds of millions of dollars per year per firm. And that gets absorbed by the end user, the consumer. In Africa, the mines, like in the Congo, there’s always a level of security that needs to be maintained. The people in charge are normally security specialists, like myself, and we get paid a fair amount of money. It does depend on the threat level in a particular country as well, but whatever happens, where there’s security involved, the consumer carries the costs.

What’s the role of a PMC in this kind of environment?

The role of the PMC in a conflict or war zone is to free up soldiers to fight the war, and that’s what happened in Iraq and Afghanistan. A lot of people say we were just hunting the money. Yes, you get remunerated well, but bear in mind you don’t have a pension fund, you don’t have a medical aid, you don’t have a housing allowance like a soldier, and governments have done calculations which show that it’s cheaper to use PMCs than to enlarge the army, because a standing army costs you money. PMCs only get used per contract, and then we go home and we don’t have work. But if you enlarge your army and you bring more battalions and divisions you have to pay those soldiers, you can’t send them home afterwards, and that’s costly. PMCs don’t need mess halls or hospitals, nor do we have pension funds, so in reality we earn much more money than soldiers, but it costs the companies and the governments involved much less than to use a regular army.

Why are so many governments so scared of PMCs? Is it because you call yourself a PMC, but, in reality, you’re a mercenary?

There’s a very fine line between mercenary and PMC. An individual could be either and it’s the job description that defines which. A mercenary is classed by the UN and certain world powers as someone who partakes in active combat. And some support organisations are also blacklisted or embargoed by the UN. So, you need to choose your sides very well. Make sure you don’t get involved in offensive operations, make sure you go as a protector, trainer or mentor because if you go out with the military and you’re involved in operations, that’s classed as mercenary work. If you go to protect and you only shoot back when your life or your client’s life is threatened, that’s not mercenary activity. That’s self-defence. But you use your soldiering skills. So, me, as a soldier, I could go and fight a war in a country somewhere for a rebel group that’s on a blacklist or that’s anti-government, and I would be classed as a mercenary. Or I could go to the same country to protect people working on oil installations or mines or that are supported by the government or the UN, and I’d be a PMC. Choose your jobs very carefully is what I always tell the guys!

...whatever happens, where there’s security involved, the consumer carries the costs.

Would it be fair to say that a lot of governments, including South Africa’s, are very scared of the PMC concept?

Yes. And I understand why, because remember we are all guys with ex-military skills, we have been in combat zones, we know how to fire firearms, we know how to conduct combat, and I think governments are scared of them because of the potential for power. There are large corporations in the world at the moment, American, British, and so on, which employ upwards of 20 000-30 000 private soldiers on their security teams. These are guys with experience, ex-military, ex-special forces, they’ve been all over the world, and they could very easily become a force to be reckoned with. Governments, especially in Africa, with its history of coups d’état, are scared that such people could get contracted to overthrow them. History supports that view: remember the mercenaries of the old days like Bob Denard, David Stirling and “Mad Mike” Hoare? Those guys, yes, they did things that the world frowned upon and there are still things going on at the moment.

But if you look at the ratio between the good work that private military contractors do and the number of coups or wrongdoings, it’s a very low percentage. I think 97%-98% of our work is legitimate. We’re not a threat to anybody, and I hope the world realises that, not only from a support point of view against terrorism and protection but from a financial point of view, too. PMCs can really help people safeguard their assets and companies; just make sure you recruit the right companies, the right people and make sure the job descriptions and missions are of a nature that is not blacklisted, sanctioned or criminally orientated. There’s a big role for PMCs to assist business in safeguarding their assets.

The Americans seem to understand the PMC concept better than most. You end Blood Money by suggesting that more and more South Africans with your kind of background are being employed by American firms?

Yes, the Americans did not sign the 1989 UN Convention that classes PMCs as mercenaries if you partake in certain missions. They refuse to sign it. So, in their eyes, there is a big role for PMCs. They took the lead on this in the 90s in Kosovo and Bosnia – even after the ’90-91 Gulf War, they started using PMCs in a limited capacity. But it was really with the advent of Iraq and Afghanistan that it came to the fore. The American government…well, it depends who’s in power, too, because the Republicans see PMCs as an asset and the Democrats see them as a threat. But the Bush government spent vast amounts of money on private military contracting.

I’ve worked mainly for American firms in my career and they’re professional and they look after their private military contractors.

South Africans like you – ex-Recces, ex-special forces, are particularly, highly regarded?

I must say the British, and specifically the Americans, really like the South Africans. They see our value. We don’t complain, we just put our ears back and we work. Some of them that I’ve worked with, Americans and Brits, and so on, European nations like the French, you know, if the air conditioner is not working and it’s hot they complain. If they’re in Africa and the mosquitoes and the goggas bite them, they complain. They want to live in a way that they grew up. But we, for some reason, seem to absorb hardship a little bit better. And there’s the old saying: ’n boer maak ’n plan. I’ve seen that, because in scenarios where things go out of the ordinary, we box on our feet a little bit faster than most.

Business takeaways:

So, you think your business may need to hire Private Military Contractors to beef up security? If so, you need to:

1. Investigate and fully understand the level and nature of the threat the company is facing.

2. Discuss your concerns and options with professionals, including local police officials and other companies operating in the same environment.

3. Make sure you thoroughly understand local laws and regulations about what you can and can’t do: a PMC in Country A may be considered a mercenary in Country B, with severe consequences.

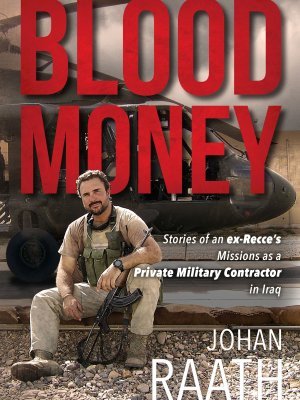

Blood Money – Stories of an ex-Recce's Missions as a Private Military Contractor in Iraq by Johan Raath is published by Jonathan Ball at R260.