South Africa’s ‘Black Diamonds’, or as we term this group nowadays: the black middle class, are far more complex than existing marketing endeavours would lead us to believe. New research tells us they straddle African collectivism and Western individuality, effectively throwing marketers a strategic curve ball. This valuable insight into a group which has been written about extensively as a market of untapped potential for brands across Africa - particularly high-end products and services - confirms what many in the world of marketing have been saying for some time: that understanding the black middle class requires getting closer to understanding the drivers and social motivations of this group.

The UCT Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing has, of course, been studying the black middle class for years; in fact, they and TNS Research gave the world the term ‘Black Diamonds’ back in 2007. Using UCT Unilever’s definition, the black middle class is seen as any black African older than 18, either living in a household with an income between R16 000 and R50 000 a month or owning a car, having a tertiary qualification or currently studying, working in a professional job or living in a city and paying rental of R4 000 or more a month.

That’s a pretty wide definition so, when MBA student Zanele Mdlekeza came to me with a research proposal which aimed to explore the black middle class and how they consume luxury motor vehicles, we knew we were working at the top end of this definition. While the entire group is highly aspirational, the visible consumer impact of having ‘made it’ is most noticeable in those who are already avidly and frequently consuming high-end brands.

Building on a 2011 study by Minas Kastanakis and George Balabanis from ESCP Europe and Cass Business School, London, respectively, Mdlekeza hoped to test their conceptual model in the South African market, specifically with respect to the psychological factors driving black middle-class consumers.

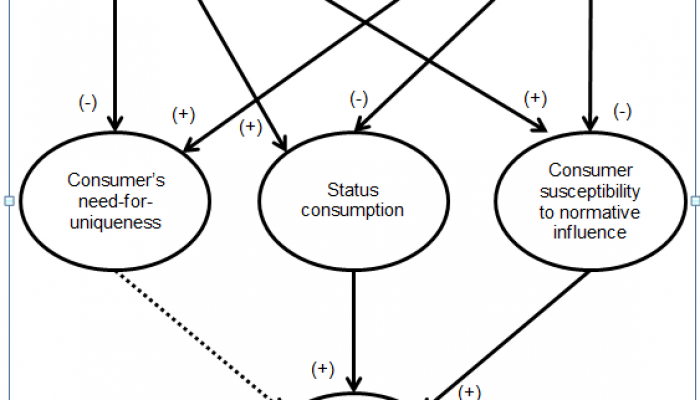

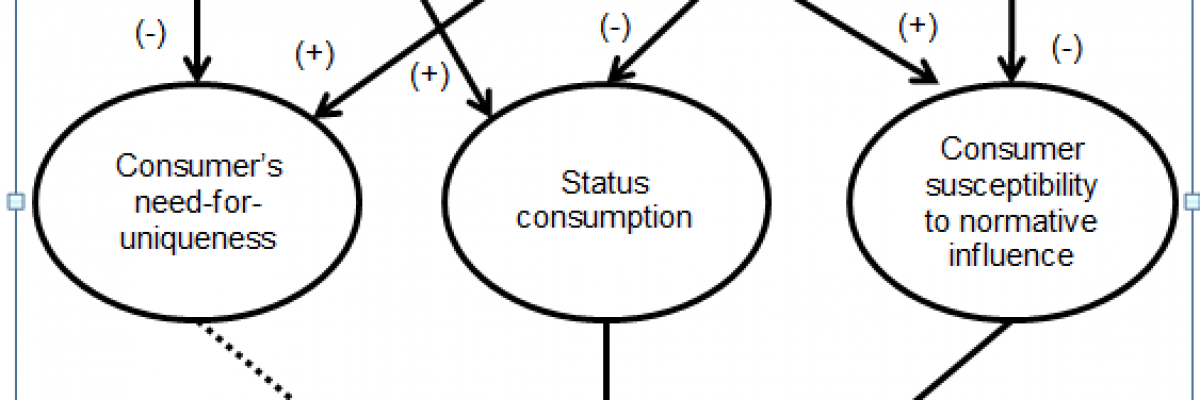

Figure 1: Psychological factors associated with bandwagon luxury consumption behaviour (Kastanakis, Balabanis)

What the arrows and assumptions represented in the accompanying illustration of the Kastanakis & Balabanis model hold is that a consumer’s desire to fit in (their susceptibility to normative influence), coupled with the status of the purchase, would lead to ‘bandwagon’ buying behaviour.

Bandwagon consumption, according to Ukrainian-born American economist Harvey Leibenstein, refers to a phenomenon whereby “the utility derived from the commodity is enhanced or decreased owing to the fact that others are purchasing and consuming the same commodity”. In other words, consumers ‘hop on the bandwagon’ and seek to own products or follow trends and fads which are prized by others. This makes followers, almost automatically, part of an informal society of sorts.

What would override this bandwagon tendency would be a consumer’s need for uniqueness. In the western application of the model, which was originally investigated in individualistic London, the influence of the uniqueness factor put a halt to bandwagon behaviour; with these consumers prizing being ‘different’ and, therefore, distinguishable from the crowd.

In the South African context, it was not surprising that Mdlekeza chose to focus on the luxury car market since these glossy marques are the ultimate sign of upward mobility. The assumption was that the overriding need to be seen as different by those in individualistic communities (in other words, the western setting) would put the brakes on bandwagon buying. But for interdependent-type personalities – like those in collectivist African cultures – uniqueness, it was surmised, would be overridden. So, in the middle class, black South African setting, Mdlekeza and I equally expected this point to have a negative impact. Interestingly, this was not the case. And the big difference came down to the notion of interdependence.

Interdependence meets independence

Mdlekeza conducted an online survey of 184 individuals identified as being black middle class and found that while interdependence certainly did exist, it also came with an element of ‘I have achieved something, so now I want to be different’. Influencing psychological factors weren’t solidly collectivist, as you might imagine. Similarly, we found that black middle-class individuals were also fiercely independent. Somehow they managed to create a strong balance between the two: independence and individualism on the one hand, and interdependence and community influence on the other.

On deeper reflection, this balance is widely characteristic of those moving into a new social class; individuals who know they have achieved something, are proud of their hard work and want to stand out from the crowd due to their achievements. However, they are still linked to their past and their roots. What Mdlekeza unearthed was a sort of watered down version of what one might expect; and it showed some western influence impacting traditional African culture.

In his book, Kasinomics: African Informal Economies and the People Who Inhabit Them, author and marketer GG Alcock made this revealing comment: “In South Africa, black Africans appear to be modern Western sophisticates. The reality, however, is that it is their traditions, not their culture, they are moving away from. Culture remains with us, an evolving living part of our make-up. Traditional is static and ritualistic. It is a mistake to see an African who on the surface is wearing western accoutrements and to believe they are now western. Africans, like many other strong cultures, modernise, not westernise.”

He goes on to say: “A major misconception in brand marketing has been that the emerging black middle class is westernising and abandoning their culture. There’s a big difference between modernising and westernising. The success of marketing lies in understanding that culture evolves, yet is retained.”

As Alcock notes, many marketers – be they in academics or on the ground – have chosen to assume, because it is easier to do so, that African cultures are more collectivist, and that the individuals who inhabit this world are too. But no. This research confirms observations, like those made by Alcock above, that South African brands need to consider and appreciate that these prized consumers are multi-layered and multifaceted and should be approached and communicated with the same degree of dynamism.

Purely independent people don’t need external validation, whereas black middle-class consumers do; and marketers need to be very clear on that fact. Take luxury vehicle advertising. With this information at hand, a luxury vehicle manufacturer in South Africa would be ill-advised to only highlight a successful young executive in a marketing campaign. Certainly, it is advisable to focus on a successful black professional in an expensive suit driving a shiny car, but do add in a girlfriend or a wife and possibly kids, because family is important to the black middle class. Once you’ve done that, then you need to offer an indication of the pride and approval such a purchase will engender from the broader community. Yes, these consumers want to show that they have made it as ‘ME’, but they also want an indication that they now belong to this ‘CLUB’ and are deserving of all the kudos that goes with that.

In her thesis, Mdlekeza arrived at the conclusion that marketers should spend time understanding the psychology of this group, adapting to their western-focused international approach to African norms, just as these consumers have done. This calls for less prescriptive communication and advertising, the skilful use of celebrity endorsements mixed with opportunities to customise products to create uniqueness.

This goes as far as the workshop floor, Mdlekeza observed. “Marketers should make their luxury motor vehicles customisable so that consumers can choose a combination of features that give uniqueness to the motor vehicle. Extending product lines to create exclusive ranges, e.g. limited editions and concept models could address the need for uniqueness through creative choice or avoidance of similarity,” she wrote.

In practice, unravelling the best approach for talking to and understanding the black middle class consumer is far more complicated that one might initially think, and it is a topic which both Mdlekeza and I believe warrants further qualitative and quantitative study. This work opens up additional questions as to how the same model might play out in the Indian, coloured and white populations in South Africa. Are they equally influenced by their exposure to African culture? Other questions which have been posed to me include whether black middle-class buyers factor in whether cars were manufactured in South Africa, and how deep the international model pull is.

While Mdlekeza’s thesis examined luxury car brands as a whole, the BMW brand features highly in the study. For a dominant marque like BMW, inclusion in such a study also holds another important gem: South Africa’s black middle-class consumers are deep and critical thinkers, they want to know why they react to luxury brands in the way they do. For any brand, such inquisitiveness is both a blessing and a curse. You have to stay on your toes, live up to your brand promises and ensure that you nurture your consumers and their perception and experience of your brand. The pay-offs, from a luxury, brand-savvy, group perspective, of fostering this level of understanding are significant and long term.

they straddle African collectivism and western individuality...

...black middle class individuals were also fiercely independent...

South Africa’s black middle class consumers are deep and critical thinkers...