Small and medium-sized business owners in South Africa see themselves as ambitious, capable, honest, responsible and broad-minded. They expect their people to work as hard as they do; they value fairness and prefer to keep their heads down and complaints to a minimum. But these essential cogs in the economic machine are not always treated well by their bigger counterparts. In fact, many small business owners surveyed by GIBS believe there is a worrying ethical gulf between small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs) on one side and big business on the other.

Gideon Pogrund, director of the Centre for Business Ethics, explains that in association with E Squared, the empowerment company of investment company Allan Gray, GIBS set out to better understand the broader business environment in South Africa by focusing on the SMME sector. The telling report of the SMME survey, which forms part of the broader GIBS Ethics Barometer study, will be released in the coming months.

A worrying abuse of power

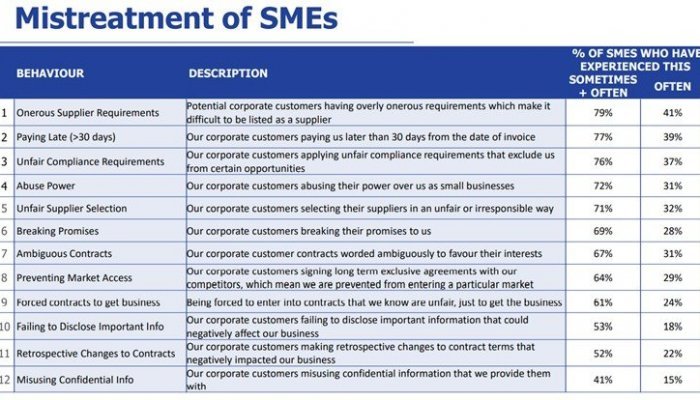

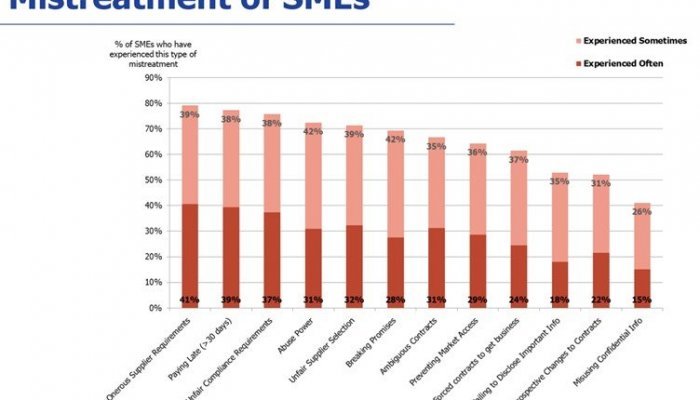

“The results are rich, and there is a lot to talk about, but I think what’s most striking is the reported treatment of SMMEs by big business,” says Pogrund. “There are some really shocking, even horrific, findings.”

These include:

- Onerous supplier requirements - “SMMEs certainly don’t get the best price or terms; however, they are expected to pay cash for goods,” commented one respondent.

- Paying late (more than 30 days) – “Our business closed as a result of corporates taking more than six months before paying us,” was one comment. Another respondent shared, “Most of the corporate companies did not pay us. To date, we are still trying to get paid for work done in January and February 2020. We spend much time and money trying to get paid for services already rendered. It is really frustrating.”

- Unfair compliance requirements – “We’ve, in instances, spent hundreds of thousands, employed optimally skilled and expensive experts, obtained the requisite vendor status and still not received any orders.”

- Abuse of power – “Their market dominance allows them to force discounts and lopsided contracts. They are bullies,” was one comment. Another SMME respondent said, “There is a complete lack of understanding that SMEs do not have deep resource pools and contracts are frequently abused. Scope creepage, reports, research, etc., all squeezing margins.”

- Unfair supplier selection – “Big corporates give other big corporates business (based on superficial data based to BBBEE and skills) knowing full well the business will be outsourced. Unnecessary third-party disintermediation. Small businesses are forced to do associate work at lower rates (third-party temp/casual worker in another guise).”

The following comment stood out for the finality of its views of working with big business: “I actively avoid doing business with corporates if I am able. While corporate clients allow for a scale and cost of a project not comparable to other SMEs, my experience is that the stress, politics, delays and challenges often negate the perceived benefits of working with a large organisation.”

Other notable insights

Another interesting finding to emerge around the perceived mistreatment of SMMEs was that this treatment generally increases with the age of the business, specifically up to 10 years, but then decreases somewhat for SMMEs older than 10 years, explains Professor Kerrin Myres, lead researcher on the study. “This may be due to the likelihood of older SMMEs having more established relationships with corporates, and therefore being less vulnerable to corporate abuse of power.”

Other themes to emerge included concerns that SMME owners often worked employees extremely hard and could be unreasonably demanding, often putting clients' needs above those of staff.

However, when it came to making ethical decisions, it was encouraging that SMMEs generally did not have to compromise their personal values or do business – although the reluctance to report attempted corruption was low. Furthermore, notes Myres, “Perceptions of how ethically small business engages with broader society are below the ideal range for most behaviours – with the exception of creating employment, active in developing South African society, and complying with regulations.”

What was also an interesting finding was that many founders “felt entitled to make use of the business’ assets and resources for a personal purpose”.

“There are a wealth of takeaways in this research,” says Myres, all of which should be debated. This is currently particularly relevant given the extreme pressures on SMMEs, from having to bear the brunt of the 2021 looting across the country to feeling the effects of Covid-19. The Small Enterprise Development Agency recently released information that 90% of all jobs lost up to the third quarter of 2020 (largely as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and the impact of lockdowns) came from the SMME sector, a sector government has long touted as the key to rescuing South Africa’s economy and spurring on growth.

Next steps

While it is hoped that the SMME Ethics Report will spark a national discussion about the treatment of SMMEs, the focus of the Centre for Business Ethics is on ensuring the research is interrogated, and solutions applied.

“We are about to start a process with E Squared and Business Leadership South Africa, the association representing big business in the country, convening various stakeholders to co-create ethical solutions to the problems identified in the survey,” says Pogrund. “Using our respective platforms, we will then disseminate the findings and recommendations, and this, we hope, will influence attitudes and behaviours.”

Who completed the survey?

Working with impact investment fund, E Squared, as well as GIBS’ Entrepreneurship Development Academy, the specifics of the survey can be broken down as follows:

- In total, 312 respondents fully completed the survey.

- Of the respondents, 91% were founders or owners of SMMEs. Managers made up 7% and shareholders or investors 2% of those surveyed.

- Regarding business focus, 41% of companies had a business-to-business approach, with 39% focusing on B2B and business-to-consumer offerings, compared with 20% in the B2C category.

- For the most part (85%), the businesses were small-scale, with up to 30 employees, and 47% were businesses with more than 10 years in operation, while 32% were between one and five years old and 16% had been in business for between six and 10 years. Only a sliver of the businesses assessed (5%) had been in business for less than one year.

- Demographically, Generation X (41-56 years old) dominated at 39% of respondents, just ahead of Baby Boomers (57-75) at 35% and Millennials (25-40) at 24%. Only 2% of respondents were in the Generation Z (six-24) cohort.

- Men made up the bulk of the responses at 57%.

- The majority (48%) of those surveyed were white, compared with 41% African, 5% for both coloured and Indian respondents, respectively, and 1% identified as other.