The 2019 novel coronavirus was not the first shot across the bow. That came in 2009, but we didn’t listen. Now South Africa is at war in the global vaccine battle and longing for a home-grown solution.

One year before the Soccer World Cup kicked off in South Africa, the H1N1 novel influenza virus was surging. The World Health Organisation (WHO) was on the verge of declaring a pandemic when the virus largely waned, with mercifully few casualties here.

At the time, vaccine manufacturer and distributor, The Biovac Institute, had no manufacturing capabilities and was in the process of building its facility. “The only thing we could do was to talk to the global suppliers and try to import any flu vaccine,” recalls Biovac CEO, Dr. Morena Makhoana. “That was May 2009. We only got the vaccines in March the following year.”

What 2009 highlighted was the skew that exists between the northern and southern hemispheres in terms of vaccine manufacturing capability. Through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, the US government responded by trying to initiate some capability enhancement through the WHO, says Makhoana. However, when the H1N1 outbreak fizzled out, so did the impetus to change.

“It’s quite sad that it is getting attention now because of the wrath of the pandemic. If we had similar hype or some sensitivity at the time, you probably could be talking a different thing,” says Makhoana.

Between 2009 and 2020, the world also contended with the Zika virus and Ebola, but it took Covid-19 to tip the scales. The question now is: where do we go from here?

A two-horse race

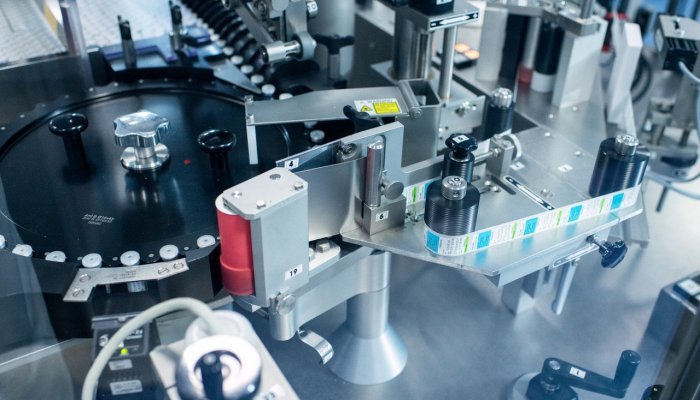

Currently, South African generics producer, Aspen Pharmacare, is contracted to do full-finish manufacturing for the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) Covid-19 vaccine. This involves filling and packaging. Aspen did not respond to questions regarding its vaccine production capabilities but is on record as saying it could produce as many as 300 million doses of the J&J vaccine annually.

Biovac is going a different route and is looking to work with an international partner to become the ‘local market authorisation holder’. “We want to be the ones directly negotiating with the government,” says Makhoana. “At the moment, J&J owns the product, and Aspen is just manufacturing for them. Biovac is seeking to work with an international partner, which gives it the rights for South Africa. So, we own the environment. That takes time due to licencing agreements and royalties.”

In mid-March, Biovac announced such a partnership with US biopharmaceutical company, ImmunityBio. At the time, ImmunityBio’s Covid-19 vaccine was undergoing clinical trials in both South Africa and the US. The partnership, as hoped, will result in knowledge transfer. Biovac is also collaborating with the University of the Witwatersrand’s AntiViral Gene Therapy Unit.

The economics at play

Partnerships of this nature are critical to building production capacity, skills and capabilities. But there is another issue to consider if South Africa’s ambition to create a home-grown vaccine is to become a reality: business fundamentals.

“There is an economic issue, which, I think, eludes everyone in vaccine manufacturing,” explains Professor David Walwyn, professor of technology management at the University of Pretoria and the former CEO of Arvir Technologies, who played a role in Biovac’s establishment. “You really need to be making 100 million doses a year to be competitive, and you can’t [in a normal year] sell 100 million doses in South Africa. So, the market is sub-competitive. It doesn’t have critical mass.”

To overcome this demand insufficiency, any local manufacturer would need to serve an international market. But this also runs into problems, explains Walwyn, since these are controlled by the global vaccine alliance, Gavi, and donor agencies, which purchase vaccines for the very countries in which South African manufacturers could be competing.

Breaking into this preferred suppliers’ ‘club’ would be challenging, from the accreditation required to the fact that any new manufacturer would find themselves competing against the originators of the vaccines. “I wouldn’t say it’s an anti-competitive club, but to be part of it, you’d have to pay very high school fees,” says Walwyn.

Not surprisingly, for an institution with ambitions to manufacture, Africa is firmly on the radar to provide the scale needed to ramp up exports. But, Makhoana explains that this would put South Africa into the COVAX facility mix, a global initiative designed to provide equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines for all countries. Of the 190 eligible countries, the 92 classed as low and middle-income (including 44 from Africa) will receive vaccines for free.

“There’s a saying we have in the vaccine world that if you want to supply vaccines in Africa, go to Copenhagen in Denmark because that’s where the UNICEF supply division is. That’s where the tender is administered,” explains Makhoana. “So, our definition of exports is being able to supply into the likes of COVAX, so that volume gets into African countries. That’s how you supply Africa, through supplying donors.”

Makhoana expects Copenhagen would be extremely happy to have a vaccine supplier that comes from the African continent, as it would “tick quite a big political box”, but the short-term dilemma is whether technology transfer partners who already supply COVAX would be willing to give Biovac volumes to supply the facility.

This, he believes, highlights one cardinal lesson: “The need to develop and have our own [vaccine], so we don’t have anybody telling us you can’t supply this market or that… You don’t want to have the shackles and limitations.”

A perfect storm

Right now, South Africa finds itself with the right combination of demand and supply. “You’ve got the Department of Science and Innovation saying we will support the technology development. Then, on the demand side, we’ve got this pandemic,” says Walwyn. “Maybe out of all of this, we will end up with a competitive global vaccine manufacturer.”

To date, South Africa has missed three key opportunities along the road to vaccine manufacturing:

- Lack of investment – Long before the dawn of democracy, the apartheid government stopped investing in vaccine production, allowing the now-defunct State Vaccine Institute and South African Vaccine Producer to erode in commercial value to the tune of R3 - R5 million[C1] .

- Lost legacy – The break in manufacturing since the mid-1990s meant that when Biovac was founded in 2003, it had to start from scratch with no licences and no infrastructure.

- Lack of urgency – Even with the H1N1, Ebola and Zika warnings, the government failed to financially prioritise the Biovac public-private project.

Now the political will seems to be in place, with President Cyril Ramaphosa saying in February, “It is urgent that we develop our own capability and not be running around the world, scouring the whole globe looking for vaccines. We must develop them here and now.”

But will this enthusiasm persist once Covid-19 starts to wane?

Here, the final word belongs to Makhoana. “My fear – and hopefully this time it won’t be true, that the enthusiasm wanes as the pandemic wanes – is that we don’t lose the momentum…because we need to be ready for the next one.”

A brief history

When it comes to vaccine production in South Africa, there are two names you need to know: Aspen and Biovac.

JSE-listed generics leader, Aspen, was founded in 1997 by Stephen Saad and Gus Attridge and is now in 21 countries. In 2018, Aspen built a new R1 billion manufacturing facility in Gqeberha (formerly Port Elizabeth), with the capacity to produce about 3.6 billion tablets annually and package around three million bottles a month.

Formed as a public-private partnership (PPP) in 2003, Biovac was unshackled from these restrictions in June 2020, although the government retains a 47.5% shareholding administered through the Department of Science and Technology. Biovac completed its manufacturing facility in Cape Town in 2012 and calculates it has invested more than R800 million in infrastructure and skills to date.

Biovac’s legacy builds on two now-defunct bodies: the State Vaccine Institute and South African Vaccine Producer (SAVP). Both closed in the mid-1990s, having received a poor assessment from the WHO over the redundancy of the technology used to create intravenous BCG vaccines. In addition, the global trend at the time was towards procurement and distribution rather than local manufacture.

Professor David Walwyn was a strong voice at the time, advocating for retaining the remaining value within the facilities and pushing for a PPP with the government to create Biovac. “SAVP was closed down, and the staff has either changed or were moved to Cape Town. We then brought in, as a private partner, the Biovac Consortium,” relates Walwyn. The aim was to build the institute as a manufacturing centre.

Building up a vaccine-making business

When Biovac was formed in 2003, the initial goal was to start producing South African vaccines by 2013. “We completely underestimated the time it would take to establish globally competitive, fully integrated manufacture,” admits Professor David Walwyn. “But we did manage to get the agreement with the Department of Health to pay a price premium on procurement.”

The total budget was around R130 million, and Biovac would receive a 10% premium. That R13 million a year was clearly insufficient to finance Biovac’s ambitions. As Biovac CEO, Dr. Morena Makhoana, puts it, “When you look at it from 2003 to 2020, it looks like 17 years in total, and that’s what the government is now saying: we gave you 17 years. But how do you raise funds off of a four-year contract? How do you raise funds off an extension of two years, another two years, three years and then a six-year extension?”

What proved a gamechanger for Biovac was the implementation of two new vaccines: Hexaxim (a sophisticated six-in-one childhood vaccine) and Prevenar (a childhood pneumococcal protection).

Since November 2020, Biovac has been doing filling, packaging, labelling and quality control testing of Hexaxim for Sanofi. Annual output is four million doses for use locally. For Prevenar-13, a Pfizer vaccine, Biovac will undertake formulation. Both the quality control aspect and the formulation, which involves blending the raw materials from the supplier in big tanks before filling and finalising, highlight a growing depth of expertise.

“We’ve been quite deliberate in doing that [building layers of expertise]. Whenever we find an opportunity to go up the value chain, we maximise. Even in discussions with a partner on Covid, we are trying to swing it to a minimum formulation,” explains Makhoana.

The Hexaxim and Prevenar-13 vaccines also gave Biovac a financial shot in the arm, ramping up the state’s budget to R2 billion a year. “Suddenly Biovac was able to earn R200 million, not R10 million, and that meant they could start really trying to raise money off the balance sheet to build that facility to manufacture vaccines,” explains Walwyn.

What 2009 highlighted was the skew that exists between the northern and southern hemispheres in terms of vaccine manufacturing capability.