On board an extremely elderly Iran Air McDonnell Douglas MD-80, bound from Isfahan to Tehran last October, I could see problems all around me. Comfortably seated at an emergency exit, the exit door’s mechanism was rusted and an exposed, hollow girder also appeared rusty. I was loath to excavate beneath the piles of used sweet wrappers that had been stuffed into this cavity. The elasticated, mesh magazine holder on the seat-back in front of me had simply collapsed and its remains hung limply down, trailing onto the floor.

Shortly after the plane, originally designed in the late 70s, took off from Isfahan, we were served an indescribably bad meal. Neither I nor the two Iranian passengers seated alongside me, both of whom spoke perfect English, could hazard a guess as to the origins of two grey slices of protein. The one passenger, who had studied at Imperial College London, and completed his MBA at Manchester Business School, just closed his eyes and wolfed it down. The other, educated at Tehran and Toronto universities, rolled her eyes and pushed the mess to one side. “There was a time when Iran Air used to win major international awards,” she confided.

Much earlier that day, I saw quite a few more very elderly passenger jets at Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport as we taxied out for the flight to Isfahan. Then I had been seated equally comfortably aboard a Mahan Air BAE RJ85, like the ones flown by South Africa’s Airlink. A not-so-young product of the mid-90s, it was spotlessly clean and apparently well-maintained, a stark contrast to the plane I would fly on later.

It seemed to me that these two flights were a microcosm of modern Iran's dilemmas, giving sharp insight into Iran’s economy, including both opportunities and pitfalls.

Sanctions

At the broadest level, international sanctions have bitten very hard. First put in place by the US in 1979 after the Islamic Revolution toppled the Shah, they have been tightened several times over the last 40 years. Most notably, a global consensus began to emerge in the mid-2000s that Iran’s nuclear programme was aimed at nuclear warheads, not nuclear power. Despite Iranian denials and backed by the UN Security Council, the vice was screwed firmly shut, locking Iran out of global financial systems, causing its economy to contract and unleashing inflation. Sales of Iranian oil plunged, the value of its currency, the rial, fell, foreign assets were frozen, the cost of basic goods went up and international insurers were prohibited by the Americans from insuring cargoes bound for Iran.

The result? Put simply, Tehran has been unable to buy spares to maintain its ageing fleet of airliners, including a replacement for something as simple as a derelict magazine holder on an old MD-80. It’s like that in many other parts of the economy, too, although a strong import-replacement culture, backed with plenty of ‘mend-and-make-do’ has emerged, just like South Africa during the years of apartheid isolation.

But it’s not just sanctions. Empty water bottles rolling around the floor, sweet wrappers pushed into cavities and not removed by cleaners and disgusting meals are the hallmarks of a state-owned airline. The contrast between Iran Air and privately owned Mahan Air could not have been greater. As we know all too well here in South Africa, governments are just not very good at running businesses. In Iran, a theocratic state, the hand of government is felt in many parts of the economy but there’s clearly a younger, less constrained, highly educated and entrepreneurial side to it, too. Sad to report, Iran has an excellent education system but it tops the international ‘brain-drain’ table. Bright, well-trained young people are a major export and not one that earns much foreign currency.

Now, though, sanctions have been lifted. Following the 2015 nuclear inspection deal, Iran’s oil flows once again, assets held abroad have been unfrozen and foreign firms can invest in Iran’s oil and gas industry, as well as car manufacture, hotels and other sectors. Iran may even be permitted to rejoin the global financial system, although at the time of my visit, no international credit cards like VISA or Mastercard were accepted; it was “Cash only, please, and we’d prefer dollars or euros.”

Almost the first post-sanctions action by the Iranian government and Iran Air was to place huge orders for new aircraft with the big international manufacturers – 80 with Boeing and 100 with Airbus. Smaller private and semi-private Iranian airlines have also placed big orders, but it remains to be seen if they will be fulfilled. There are concerns about how the deals – worth as much as $40 billion – will be financed, as well as whether the US government will permit them to go through or not. (Chicago-based Boeing is an American company, while planes made by Europe’s Airbus contain more than 10% of American-made parts, which gives Washington a veto over both deals, if it should choose to use it.)

Iran and South Africa

So where does South Africa come in? We have a long history with this country of 80 million people. It goes at least as far back as the deal cut between Smuts and Churchill during World War II to allow the first Pahlavi Shah, deposed by his son, to see out his days in exile in Johannesburg.

Apartheid-era South Africa had ties to that son, himself later overthrown in the Islamic Revolution, and our modern, ANC-led democracy bought oil from Iran until sanctions turned the tap off in the mid-2000s. South Africa’s construction companies did business in Iran for many years and Sasol had an interest in a big polymer company there until as late as 2013. South Africa’s MTN is a 49% shareholder in Iran’s second-largest mobile network provider, MTN Irancell.

Right now, according to IranPartner, an agency which according to its website, helps “small to large enterprises with their strategic entry into the Iranian market,” trade flowing from Iran to South Africa is worth US$43.2 million. Major exports include fertilisers, carpets, transformers, petroleum coke and bitumen. Flowing in the opposite direction is US$52.7 million’s worth of precious metals amalgams, dumpers, mixing machinery, seeds and flat-rolled steel.

IranPartner Senior Manager Sina Akbari Mistani highlights three possible growth areas. The first is tourism which “is a great opportunity in Iran,” he says.

“Iran has a wide range of natural, archaeological and religious attractions. The government is supporting the tourist industry since it believes tourism provides opportunities for sustained economic growth and job creation across the country. However, the country lacks the infrastructure, particularly hotels. Even the capital city of Tehran has a shortage of quality hotels. Of course, this shortage creates a great opportunity for foreign hotel operators,” says Mistani.

He adds that in recent years, “travelling abroad has been picking up in Iran…there is a demand for new destinations and South Africa could attract these Iranian tourists.”

A second area is mining. Iran has large mineral reserves, according to Mistani, and “given South Africa’s strong mining industry there are great opportunities for co-operation in this area.” He notes that there are also downstream opportunities in mining, particularly in steel and steel product manufacturing, although he warns that European companies like the Danieli Group have already started making investments in the sector following the lifting of sanctions.

Finally, Mistani points to chemicals and petrochemicals, which he says “provide a huge potential for foreign businesses”. He’s doubtless aware of Sasol’s presence in Iran until quite recently, although the Johannesburg-based giant has released a statement saying it is not considering returning to Iran at present.

Mistani says “making investments in Iran is pretty easy as there are no restrictions for foreign investments”, although foreigners may not buy land. Company registration is “relatively straightforward” and takes 2-3 months to finalise all the administrative steps.

He does caution that it’s advisable to work with a local partner.

“As the country has been cut off from the global economy, the local business environment grew with its particular intricacies,” says Mistani with a certain delicate understatement.

Seeking friends

At macro level, the Tehran government is building a global consensus to back its position against US President Donald Trump. Trump has promised to tear up the nuclear accord, describing it as “the worst deal ever”. The Iranians are at pains to point out not only their compliance with the accord but their commitment to it, a position backed by the International Atomic Energy Agency and the key European signatories.

“One of Iran’s victories is that four years ago, the US could make the whole world come to a kind of consensus against Iran. But right now, today, Iran could do the same thing – make the world reach a consensus against Trump,” said Deputy Press and Information Minister Hossein Entezami, speaking to Acumen in Tehran.

Entezami also made it clear that his country is looking for investment, although it remains locked out of the global financial system. According to Entezami, construction might be a possible avenue for South African business, but so too would tourism, in which this country is a world leader.

During a visit to the Majles – Iran’s Parliament – Tehran City MP Seyyed Farid Mousavi also pointed to tourism, but wanted to see it going both ways. Mousavi, who is also vice-president of the South Africa-Iran Friendship Group, made a call for a direct flight between Tehran and Johannesburg, although he conceded, after a question from Acumen, that the flight would have to come first to develop sufficient demand amongst tourists in both countries. He added that on the Iranian side, Mahan Air had expressed an interest in the route.

Another source connected to Iran’s tourism industry, who preferred to remain anonymous, was less sanguine, at least about South Africans and westerners, in general, visiting Iran in large numbers.

“There’s no alcohol, therefore no nightlife, and no beaches,” the source told Acumen, referring to the Islamic Republic’s strict ban on booze, as well as beaches which are segregated according to gender. Women must remain covered at all times, whether on the beach or not, and men may not wear shorts.

Here again, though, the tension between – for want of a better phrase – the old and the new Iran is evident. Immediately after the Islamic Revolution, the dress code, particularly for women, was very strictly enforced. Also during the era of the last president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, described in western media as a “hardliner”. But now, under his successor, “reformer” Hassan Rouhani, Acumen observed a very wide range of headscarf fashions, ranging from a full chador, which leaves only the oval of the female face exposed and hands beneath the wrist, to relatively small pieces of coloured cloth pinned to the very back of the head, revealing 70%-80% of the head and hair. Short sleeves for men, previously forbidden, are now acceptable.

What makes Iran so difficult to comprehend, at least for the South African mind, is that both Ahmadinejad and Rouhani were chosen – if that’s the right word – by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, himself a former president. As Supreme Leader, Khamenei controls the 12-member Guardian Council, which in turn must approve any legislation passed by the Majles. All Parliamentary and presidential candidates must be approved by the Guardian Council, while the Supreme Leader controls the armed forces, the judicial system and all key governmental institutions.

Again, put simply, that a “hardliner” like Ahmadinejad could be followed, after an intensely fought election campaign, by a “reformer” like Rouhani, means that Supreme Leader Khamenei himself must be aware of, and – maybe – struggling to balance the tensions at play in his nation.

Etiquette

At a personal level and during an admittedly brief visit, the Iranians encountered by Acumen were friendly, welcoming and very interested in South Africa. The usual precautions about valuables and hotel rooms apply, although one South African journalist in our group left her cellphone on the back seat of a taxi. Half an hour later she was astonished to be called the hotel’s reception desk – the taxi driver had found the phone and driven across Tehran to bring it back.

Officials we spoke to were punctual, well briefed and well informed. We had been warned that Iranians are habitually late but found that not to be the case. Business cards are exchanged and men shake hands, although women do not, except with other women. Business attire seemed uniform: suits, well-shined shoes and formal shirts but no ties for men, and long-sleeved tunic and trousers with a headscarf for women. In government offices, all female employees wear a full, black chador. Conversation is polite and relatively formal and Acumen left with the opinion that trust would have to be earned, and not given easily or quickly.

IranPartner’s Sina Akbari Mistani suggests that “Iranian businesses put significant importance on face-to-face meetings, building relationships and doing business based on bilateral trust. Thus, you may find people making large deals without a single contract or you may find an Iranian partner acting against their contract with their foreign partner mainly because they do not believe in a piece of paper dictating their interactions.”

Language is also a critical factor. Whilst many Iranians speak good to excellent English, a large proportion, especially in government, speak only Farsi. Expect any official business with government to be conducted in Farsi, so you will need a translator.

Business structures can be very different from South Africa: many organisations are run by religious charities called bonyads. Reports in western news media also state that the Islamic Revolution Guards Council, often referred to as the “Revolutionary Guards”, is deeply involved in many areas of business. “They’re everywhere,” one source who declined to be named told Acumen in Tehran.

All IranPartner’s Mistani would say on this subject was that “based on the particular regulations that a foreign company needs to comply with, it is crucial to run due diligence on the partner to make sure the Iranian entity is not sanctioned.”

With President Trump itching to tear up the nuclear deal and reimpose sanctions, that’s wise advice. Iran is no different from anywhere else: if you’re venturing there on business, excellent homework is paramount.

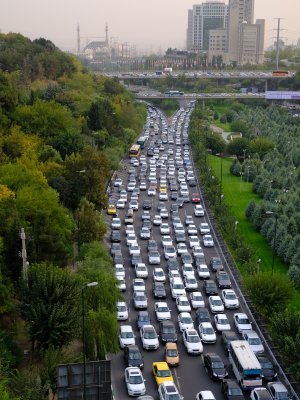

Tehran’s climate is not unlike that of Johannesburg, with plenty of air pollution trapped in an inversion layer. With 7.5 million people, it is much bigger and the traffic is dreadful, especially in the late afternoon. We regularly experienced trips of two hours or more as we attempted to cross the city. Do not think of attempting to drive yourself – the rules of the road are idiosyncratic, to say the least – and Iran has the highest road death toll in the world.

On arrival at Imam Khomeini International Airport, expect long delays – it took your correspondent nearly two hours to clear passport control – and yes, South Africans do need a visa.

Iran’s cuisine is superb with plenty of grilled meat, flatbreads and rice. Sauces are lightly spiced, and more often with fruit rather than heavy doses of chilli.

One final caution: most toilets in Iran are of the ‘squat’ variety, rather than SA’s ‘sit-upon’ kind. You may need to ask yourself if this could be a problem? (And what then? Practice, practice and more practice is the only way!) Toilet paper is not always present so you may need to carry some with you, if that’s your preference. In almost all instances the facilities Acumen encountered were spotlessly clean.

*Chris Gibbons travelled to Iran as a guest of the Iranian government.

“...international sanctions have bitten very hard”

“Bright, well-trained young people are a major export and not one that earns much foreign currency”

“...the taxi driver had found the phone and driven across Tehran to bring it back”

“Iran is no different from anywhere else: if you’re venturing there on business, excellent homework is paramount”