The challenge of a return to prosperity in the months and years to come is vast and unique. That does not mean we are lost for applicable tools to achieve it. Economic prosperity is a phenomenon with near-universal ingredients. That is, we can design for economic prosperity at a country level. It is the outcome neither of mere good fortune nor necessarily any particular policies. Rather, there are fundamental, big components which governments and societies can implement to reliably enable and boost prosperity.

Of course, there is no total consensus on what this recipe for success is. There are multiple independent models. They are mutually reinforcing in many ways. One common feature is that each is documented and freely available to any administration which chooses to adopt it and adapt it for the context. These are culturally and geographically agnostic.

Below are several prominent models, including the in-house version from the GIBS Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM), explained and compared. But first, consider a counterintuitive case for what a platform for prosperity in Africa is not.

Dead aid

The most obvious tool for many is international aid. It seems logical. Rich countries can fund poor or crisis-hit countries into prosperity. Lusaka-born economist and author of Dead Aid, Dambisa Moyo, argues the opposite. While in favour of humanitarian and emergency aid, the former Goldman Sachs head of economic research and strategy for sub-Saharan Africa argues that the US$1 trillion-plus that has gone into development aid to Africa in the past 60 years has been not just ineffective but “malignant” and unsustainable. “Are we creating an environment in Africa to make sure that in 10 years, 20 years, 30 years, African governments are going to take responsibility?” she asks. “We are not Americans. We are not supposed to be tapping into the American tax base. The American society does not operate by sitting around and waiting for handouts. Why should we as Africans?”

Moyo is most vociferously critical of aid for its “thwarting accountability mechanisms, encouraging rent-seeking behaviour, siphoning away talent, and removing pressures to reform inefficient policies and institutions”. She argues that this crowds out domestic exports, raises the stakes of conflict and perpetually sustains the vested interests that thrive on Africa’s dependence. If not aid, what?

Six killer apps

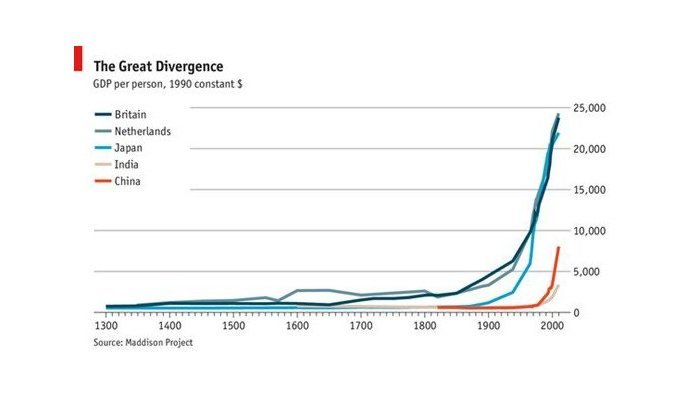

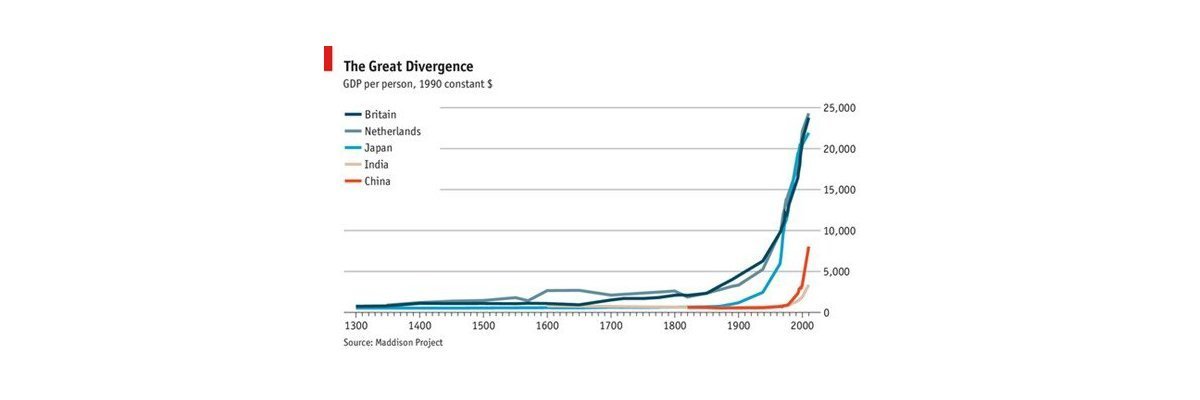

Scots-American historian, Niall Ferguson, achieved acclaim for his formulation of national prosperity in his 2011 book, Civilisation: The West and the Rest. Later popularised by a TED Talk and television series, the book outlines what Ferguson calls the "six killer apps". At the American Academy in Berlin, Ferguson explained that these "six killer apps refer to key institutions", but he named them as such to "catch the attention of his 17-year-old son". These key institutions, he says, enabled the rise of Western civilisation to global dominance over the last five centuries.

Ferguson argues not only that these six ingredients were the definitive causes of the so-called “great divergence” that saw the West race ahead of the “Rest”, as the book puts it, but that they are “downloadable”. And modern society means they work even better today than they did in the past: “Any society can adopt these institutions, and when they do, they achieve what the West achieved after 1500 – only faster.”

Figure 1: The Great Divergence. Graph: The Economist (2013)

Implying no order of importance or even any necessary order of download, Ferguson lists his six killer apps: (1) Work ethic, (2) Competition, (3) Science, (4) Property rights, (5) Consumer society, and (6) Medicine.

The six factors

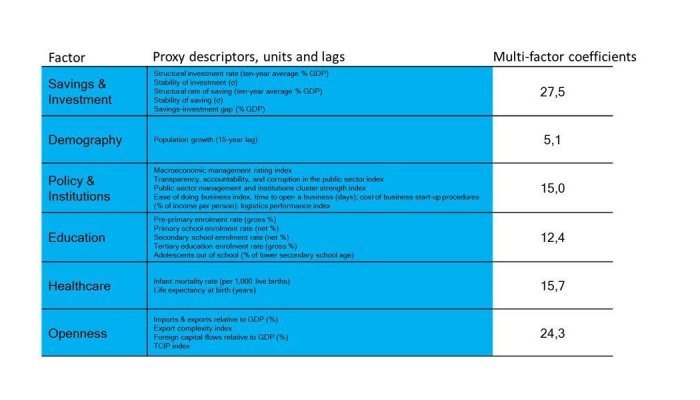

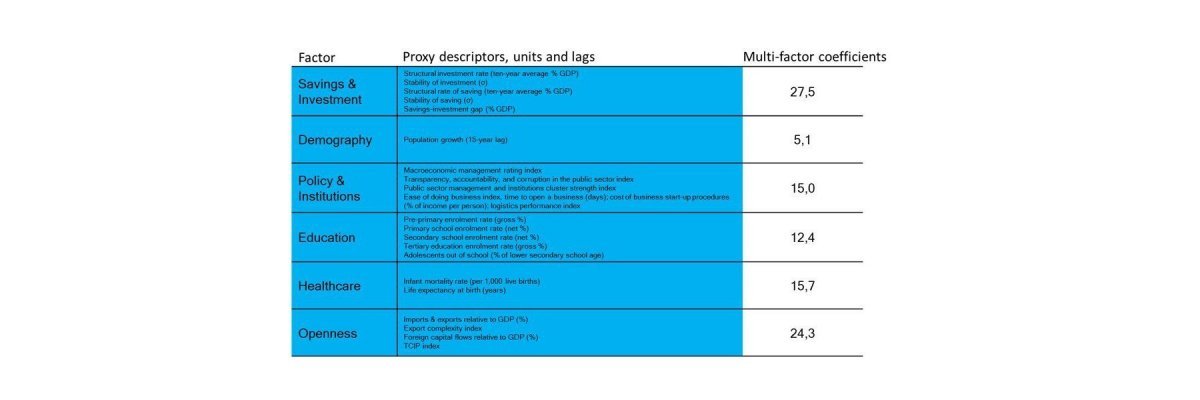

It may be a coincidence that Ferguson’s model and the in-house model employed at the Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM) both settle on six components. However, their overlaps in substance and nature are instructive. Consider that Ferguson’s apps are the result of reasoned argument by a trained historian, while the factors are mathematically derived using economic tools.

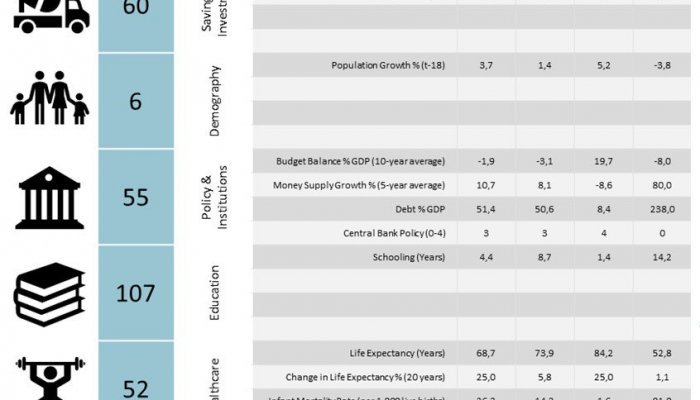

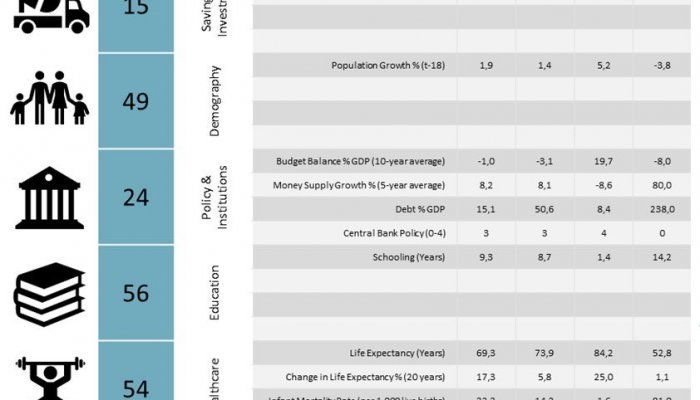

The 6-factor model of prosperity was developed by CAMM director and GIBS Professor, Adrian Saville. The “Saville Sixpack” as it is known to MBA cohorts, calculates the six ingredients most closely associated with long-term economic prosperity using data going back more than 60 years. The keystone is “long-term” – this is about decades, not months.

Figure 2: The six factors most closely associated with long-term prosperity

Six of one, half a dozen of the other

Several overlaps between the killer apps and the six factors are straightforward. Medicine and healthcare, for example, are perfect substitutes. Science and education beg little further exploration.

One parallel that does invite scrutiny is that between Ferguson’s consumer society app and the factor of elevated savings and investment. At first glance, one may see conflict between these. Money that we save is money that we can’t use for consumption. The apparent conflict may simply be one of time horizon. True, in the short term, we cannot consume what we save or save what we consume (“have our cake and eat it”). But savings fund investment in the longer term, which enables a consumer society. Both formulations target the same thing: a vibrant consumer economy.

Sharma’s rules

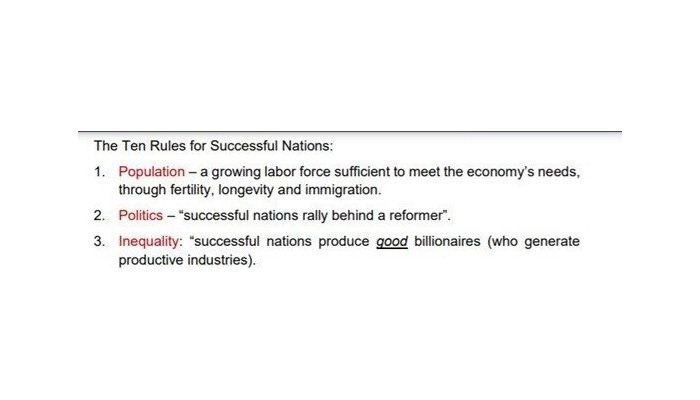

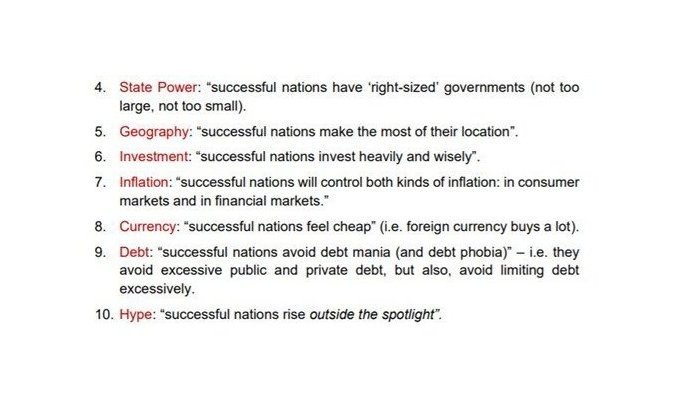

Ruchir Sharma, the head of emerging markets and chief global strategist for the global emerging markets team at Morgan Stanley, models prosperity with his “10 rules”. From this broad base, in September 2020, he and his team screened the world’s major emerging and developed economies for “key strengths that will prove critical in the post-pandemic era”. Sharma lists these pithily: “A strong domestic market (or unusual export prowess), low debts, a competent government, and digital sophistication.”

Those familiar with Sharma’s book, The 10 Rules for Successful Nations, may draw the same parallels that he does between the four strengths he identifies above and four of his 10 rules, namely the rules on “geography and trade, debt, state competence, and investment”.

Figure 3: Sharma's model of national prosperity is formulated into 10 rules

One sees the direct lines to the factors of connectedness; policy and institutions; and saving and investment. Sharma’s “population” rule aligns almost completely with the factor of “demography”.

Most striking from the application of this to the latest data is the unimpressive showing of the world’s only two economic superpowers. Sharma argues that China and the United States fall short primarily due to “heavy debts and by doubts about how their governments handled the pandemic”.

Topping the list of likely post-Covid superstars are Germany, Finland, Switzerland, Vietnam, Taiwan and Russia.

The standout developing nation on the four-part score is Vietnam. The formerly communist state is a poster child on several markers that all emerging economies are chasing. It was attracting investment into its export factories at an accelerating rate before the pandemic hit. The country was meanwhile moving up the manufacturing ladder from lower-value work to higher-value work (that is, from sewing shirts to making semiconductors), and leapfrogging from legacy technology like landlines directly into the digital era. Ignoring some small outliers, Vietnam is forecast to finish 2020 as the world’s fastest-growing economy.

Apps, factors and rules. None of these models solves the problem; there is no injection for national prosperity. But in a divided world of competing narratives and vast new challenges, these are thoroughly evidenced frameworks. These are platforms in a stormy sea.

The six factors and Africa

We at the GIBS Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM) applied the 6-factor model to the latest 2020 data for a selection of African countries. The results are represented below. Overall scores and rankings and those for individual factors, provide guidance on areas governments should prioritise for a successful revival post-Covid-19 and lay the groundwork for prosperity well beyond.

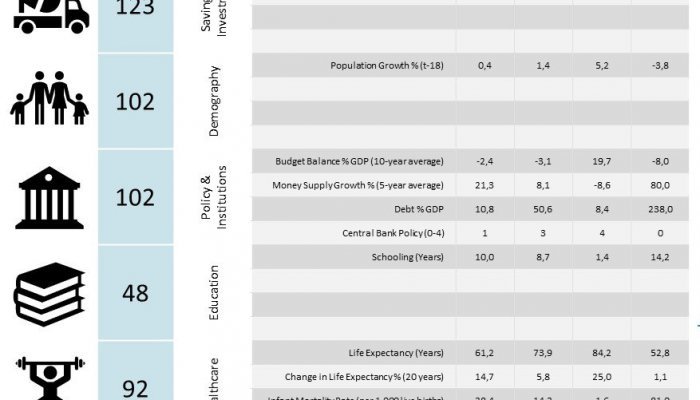

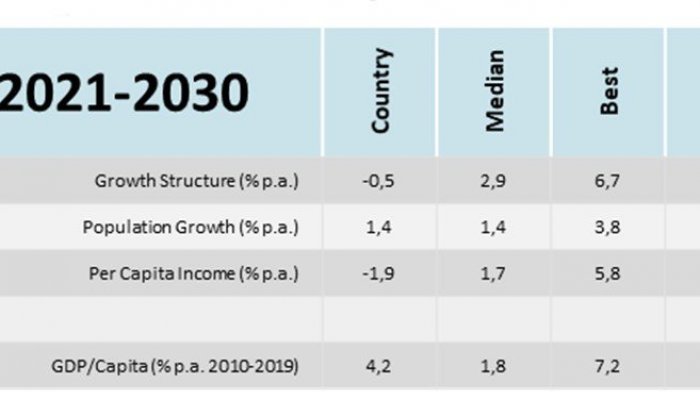

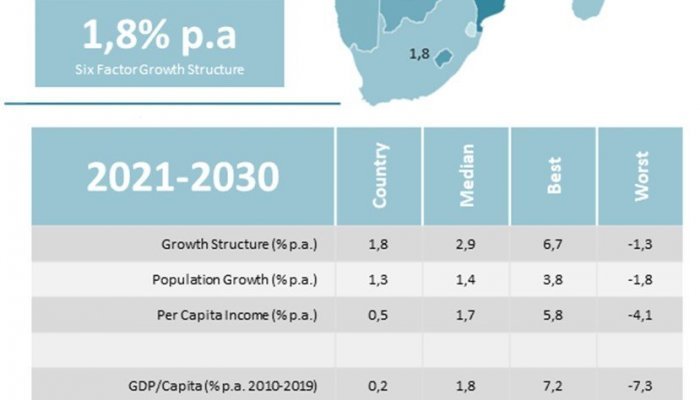

Ranking 89th out of 125 countries tested on the 6-factor model, South Africa has several clear weaknesses. Poor healthcare (rank 107) will come as no surprise. Covid-19 and associated lockdowns have loaded burden upon burden. This highlights the importance of the debate around the government’s proposed National Health Insurance (NHI) policy. We cannot afford to get this wrong. The other extreme is no less important. With a top score ranking of 43, stable policies and institutions remain a bastion to defend. Judicial independence, central bank integrity and fiscal governance are non-negotiables if the country is to find prosperity in the years to come. As it stands, the model suggests a maximum potential growth rate of 1.8%. Viewed against a population growth rate of some 1.4%, this is as good as stagnation.

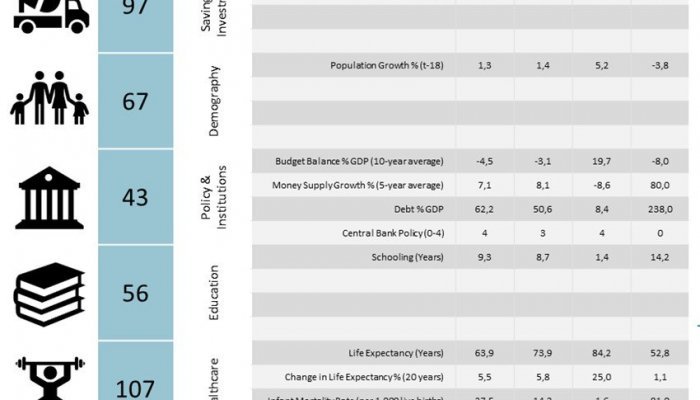

Just a fraction of South Africa’s size by population (some 2.3 million to South Africa’s 58 million), Botswana strikes a very different note on the six factors. At 46th out of 125, and with just one score outside the top 60, the nation’s primary challenge (and, by implication, opportunity) is unambiguous. The 6-factor model suggests the first factor to improve ought to be openness. Especially for a landlocked nation with a small population, connectedness with other countries is a vital economic lever. Opening up to more of the productive kinds of movement of people, products and ideas represents a strong recovery tool for Botswana.

Zimbabwe’s figures may seem to do nothing more than confirm a deep and enduring economic and human disaster. That much cannot be denied. It also confirms a widely commented-on suspicion that its well-regarded education system has somehow hung on better than other factors. If nothing else, that is a foothold on an otherwise smooth slope.

Rwanda’s middling ranking of 84th out of 125 obscures the variety of individual factor scores. They range from an elite 6th place for demography, up to 111th for openness. One striking contrast is between this highly positive score for a youthful population and the poor positioning on education, at 107th place. The 6-factor model thus suggests attractive long-term gains from improving education of this young population.