One of the reasons the township economy – also referred to as the informal or ekasi (community) economy – remains so elusive and hard to quantify, is that accurate and up-to-date data is in short supply. There are, however, indications from banks and businesses on the ground that the informal sector could account for up to 17% of South Africa’s total employment and represent in the region of 1.2 million business.

The 2022 South African Township CX Report, produced by Rogerwilco and Survey54, notes that with almost half of urban South Africans living in the roughly 532 townships dotted around the country, these consumers represent an important and growing market. “The township market represents hundreds of billions of rands of spending power,” the report notes, highlighting among other trends increased spending at supermarkets that are springing up in and around township malls.

Referencing the changing dynamics of South Africa’s townships, Jose Gomes, the business development head for the community economy segment at FNB Commercial, challenges any visitor to today’s townships not to notice the presence of some type of mall.

“There is always a Checkers, always a Pep; these days you’ll see a Roots or OBC butchery, some cellphone shop, you might see Ackermans. The banks are all going in too, you’ll see an African Bank, you’ll see an FNB, but 20 years ago you didn’t see that. Twenty years ago people would buy stuff on their taxi route, but now people don’t have to lug stuff on the taxi.”

Other companies opening branches or seeking partnerships with township entrepreneurs include the likes of Dunlop, Mr Price, Pick n Pay, and tile retailer CTM, alongside perennial champions of the township market such as Coca-Cola, KFC, and telecoms giants MTN, Vodacom, and Cell C.

GIBS MBA alumnus Gomes explains that FNB Commercial has been “working on this for a fair amount of time”, with early forays dating back to around 2017. In the process, Gomes says his team has “come across very, very big businesses with proper turnovers across multiple business sectors, such as wholesalers, taverns, restaurants, funeral businesses … the list goes on.”

Other up-and-coming entrepreneurs include the likes of Letebele Diketana, a pharmacist by profession, who opened his first Botleng Pharmacy in Phola, Mpumalanga in 2013 and today boasts six pharmacies in and around Gauteng and Mpumalanga. Botleng’s rapid expansion was financed thanks to credit secured from FNB in 2013, which enabled Diketana to, in his own words, “boost my inventory, marketing resources and shelving. This helped to increase my market, my clients and pharmacy size.”

Another high-flyer is Sheldon Tatchell, founder of the Legends Barbershop franchise, which today operates 63 stores across South Africa from Tembisa to Mitchells Plain. Tatchell's journey started in 2011 with a set of clippers and a chair on his stoep in Eldorado Park.

Working closely with businesses of this ilk is helping banks – the financial faces of the formal economy – to identify ways in which to serve the township consumer. Part of this evolving relationship, explains Gomes, lies in appreciating that the township consumer comes from a different vantage point around money management, generational knowledge, and trust in the banking system.

“I finished school and opened a bank account; I got a job that paid me into that account. I was lucky because I understood how things worked; there were certain behaviours I’d been surrounded by that influenced my behaviour and understanding,” says Gomes. “I know a whole lot of stuff, but it’s the result of an accumulation of many behaviours and habits. Unfortunately, many people don’t have this benefit, so they either get into trouble in a personal capacity or do not get the full benefits of the existing financial service offerings since they were not aware of the expected behaviours and ways of working.”

Building strong community businesses

If this is the situation on a personal level, then the financial knowledge gap for community-based businesses is just as telling. It is in this space that FNB believes it has a role to play by working with established business owners and energetic entrepreneurs to help them incorporate banking tools to grow and develop their businesses.

“There is an explosion of new businesses at the moment,” says Gomes, noting that in a tough economic reality with high unemployment many people are turning to self-employment to make a living. “We go out into the field a lot and we see some very, very good businesses, but they are often run in a way that mean they aren’t able to maximise the opportunity.”

For FNB, this highlights the importance of having discussions around products such as business insurance, which means a stolen or damaged vehicle doesn’t have to end the earning potential of an Uber driver or an up-and-coming transport company.

These conversations are, however, meant to support and not to diminish the innate business savvy of many of these founders. After all, says Gomes, the community economy already boasts intricate systems and extensive value chains. Gomes notes that even a potato seller with several roadside locations operates as part of a complex ecosystem that includes sourcing from the wholesale Joburg Market, supplying and paying vendors, transport, and storage.

“You’d look at her and think she’s an informal business, but what’s informal about that?” he asks. “The system is understood and it works, and it’s been working for years and it moves huge volumes. The challenge is that the entire value chain operates almost exclusively with cash. There are still several friction points in digital payments, whether it be cost, accessibility, or even convenience, that require attention in order to replace cash.”

This continued reliance on the cash economy accounts for why the community economy remains “unseen” and hard to quantify. While, for some, it remains a strategy to stay off the radar of the taxman, it also means there is an automatic cap on how much these businesses can develop, simply because they operate outside a system that relies on sight of their business activity to afford them access to credit.

A challenging market

While big companies like Shoprite have a clear focus on township expansion, that is not to say that operating in the township economy doesn’t come with its challenges.

“The more we understand about the community economy, the more we realise the challenges we’re facing,” says Gomes, singling out issues around infrastructure which, currently, include electricity outages and roads that are not fit for purpose, as well town planning that stubbornly fails to evolve with the changing needs for emerging high streets and nascent business centres.

“We run our country based on how things run in Sandton,” says Gomes, noting that taking Sandton rules and applying those to townships is wrong. “We must understand how townships operate and then see what we need to do to help them.”

With the formal face of the South African economy showing signs of wear and tear, the fresh-faced township economy is finally drawing big names and brands across the divide. How both big and small players approach this gradual blurring of the lines will determine what this new composite face looks like in the years to come.

eKasi-style banking

The formal banking sector in South Africa does not always engender trust among consumers ekasi.

According to Jose Gomes, the financial services sector must continue investing in the community economy if it is to build trust, specifically around concepts such as fees and helping customers understand the trade-offs between fees and value they receive from financial services.

“In our way of working, we understand things like debit orders and monthly fees, but these don’t always sit well in the township economy,” he says. Gomes believes progress is being made to help instil an understanding of the value banks have to offer.

Having more branches on the ground in townships, where regional teams can engage face to face with consumers, is just one way of bringing financial services closer to the market. Another factor is the growth of digital banking, which resonates with the township consumer.

The 2022 South African Township CX Report notes that more than “60% of respondents say they use banks to put away their funds. Banks are seen as a safe option, even though returns are perceived to be smaller than some options available through stokvels.”

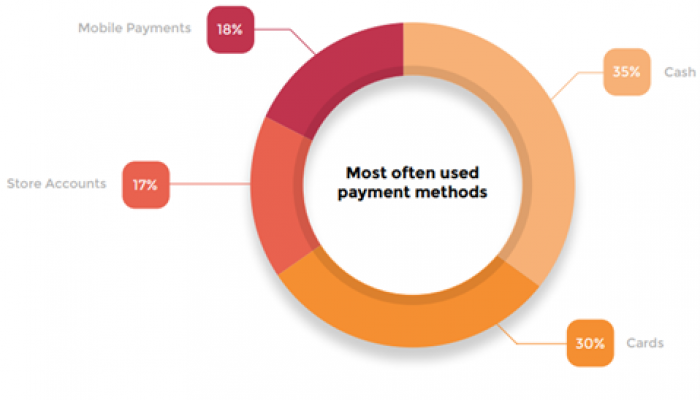

While cash remains king as the most-used payment method at 35%, spending via bank cards (30%) and store accounts (17%) remains high. Increasingly, mobile payments (18%) are coming into their own, with this figure likely to climb with smartphone penetration in townships. Already, the youth market is showing a propensity to make use of e-commerce channels, says the report.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In the past, South Africa’s informal economy has taken second place to its formal economy, but companies in search of long-term growth are now looking towards the mass market.

- Leading retailers such as Shoprite and Mr Price, as well as banks and cellphone providers, are focusing on developing a presence in South Africa’s townships.

- Operating in informal markets does come with challenges, from infrastructure deficits to particular consumer needs and payment preferences. It is not sufficient to simply cut-and-paste formal market models into township spaces.

- The range of operations undertaken by the estimated 1.2 million township-based businesses in South Africa is vast, spanning a spectrum from very large going concerns to businesses living hand to mouth. Collectively, the activity generated by these business is significant and growing. The growth, however, is being hampered by knowledge gaps and know-how around how best to leverage the formal banking system.