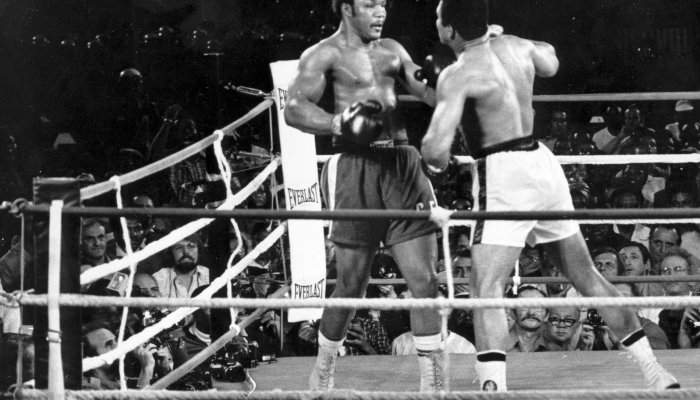

It was four a.m. in the morning, the date October 30, 1974. Banks of white hot lights cut through Kinshasa’s steamy night air, illuminating the square ring. Some 60,000 fans were packed into the stadium and many millions more were in front of their TV sets or in movie theatres around the world. “The Rumble in the Jungle” was about to unfold, a classic showdown between the reigning Heavyweight Champion of the World, 25-year old George Foreman, and his 32-year old challenger, former champion and now veteran, Muhammad Ali. Heavily muscled “Big George” was unbeaten in his 40 fights, 37 won by knock out. Pound for pound, pundits rated him as perhaps the most devastating puncher boxing had ever seen. The bookmakers had him as clear favourite: although Ali in his prime had won many of his fights through sheer athleticism and agility, it was highly unlikely the older man would be able to absorb Foreman’s fearsome firepower. So what does this have to do with business? Read on….

First, just like in the heavily-hyped run-up to a world heavyweight title bout, we need to set the scene. South Africa is in the grip of tough economic circumstances and has been for a while. How bad is it? Well, an easy way to capture economic performance, or the lack thereof, is to look at per capita income changes. The tale-of-the-tape is that we have been in a per capita income recession for a number of years. If you compare the performance of per capita income over the course of the Zuma administration to the halcyon days of President Mbeki, it pales in comparison. In fact, to find economic performance as poor as this, we need to return to the dying days of the apartheid regime under Botha and de Klerk, when per capita incomes had been in recession for the best part of a decade. To put some numbers to it, per capita income growth under the Mbeki administration ran at about 2.5% a year, while under Zuma it has been flat-lining at 0%. If it were a real fight, the ref would have stopped it by now – or Zuma’s corner would have thrown in the towel!

For overall GDP growth, 2016 looks like it delivered a meagre 0.3%. Allowing for an improvement in commodity prices, an end to the drought in most provinces and energy stability, 2017 might be 1.0%-1.5% better. Yes, that’s an improvement but it’s hardly robust. In turn, even if this better GDP growth transpires, once we adjust for population growth of 1.7%, 2017 looks like it will add a year to South Africa’s aggregate growth in per capita income of 0% over eight years will be extended to a nine-year run.

So how should businesses that find themselves appearing in this tough economic ring prepare for the big fight that almost certainly lies ahead?

Escape Velocity

Well, just like the storied boxing trainers of yore – Angelo Dundee, in Muhammad Ali’s case in Zaire[1] – we need to study the records. For a man like Dundee, that would have involved watching and analysing tapes and films of his charge’s next opponent. In my case, my colleagues and I have been watching a set of more than 2,000 companies over nearly 20 years and analysing their competitive strategy and resultant performance. A key element of this work was to help us establish if there were common attributes or elements of identifiable behaviour or business DNA that allowed these companies to achieve what we call escape velocity.

Escape velocity doesn’t mean that these firms have immunity to economic circumstance. But it gives them buoyancy and a record that stands out relative to their industry and economic peers.

The way we identify these businesses is through their ability to achieve top- and bottom-line business growth, ahead of inflation and economic growth. Inflation, because it’s a nominal number – if you have 5% inflation and the company has grown by 5%, the company hasn’t actually grown. And we put economic growth into the mix for the same reason – because if the economy has grown 2% and the company has grown 2%, then the company has really just been treading water in terms of economic market share. Our metric to measure true business performance is to say a company needs to be growing faster than both inflation and economic growth and it needs to do that in an uninterrupted fashion. These are companies with escape velocity.

Notably, what we found is that many of these businesses are not the ‘usual suspects’ that feature in the narrative around South African champions. That’s a story which often emphasises that such companies have to be big and global. Naspers, Richemont, and Shoprite are great cases in point. However, whilst these are remarkable businesses, there is a different set of companies that have evidentially even more impressive business performance with at least 10 years – and sometimes more than 15 years – of uninterrupted top- and bottom-line growth.

This cluster, which has achieved escape velocity in the South African landscape, include EOH, the services and technology group; insurer Clientèle Life; Aspen Pharmacare, one of the ‘obvious giants’; Famous Brands, which looks after the likes of Wimpy, Mugg & Bean, Steers, Debonairs Pizza and many more; and the Imperial Group, which for a period stood out with extraordinary performance. In the construction sector, head and shoulders above its peers is Wilson Bayly Holmes-Ovcon (WBHO); in banking, it is Investec and Capitec; and in consumer services and retail, Mr Price, Truworths, Shoprite and Bidvest.

Key to note is that if you look at the recent performance of some of these businesses, it’s evident that a couple have stuttered. For instance, WBHO has fallen onto difficult times relative to its 20-year track record. Notwithstanding that, its performance remains well above the industry. Mr Price has recently delivered disappointing numbers, but that’s on the back of 15 extraordinary years. The critical point is that remarkable businesses can hit tough times – and in the worst instances lose their way – and that achieved success for a period doesn’t mean that a business is assured of success in all times.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Not Just in SA

Having flagged the South African companies and identified many of them as being “unusual suspects”, there is a lovely resonance with international research done on the same subject by Professor Rita McGrath of Columbia Business School in New York. In fact, our research was developed off her model. McGrath’s question started with exactly the same premise: there are some businesses that have achieved uninterrupted performance. Who are they?

McGrath identified from a set of 5,000 companies that for businesses to be able to achieve this uninterrupted top- and bottom-line growth is overwhelmingly a minority sport. She started with a survey period that covered just five years. She was staggered that so few businesses could do five years in a row without interruption. And so she went to a different five years and found an almost identical result: in both five-year surveys it was fewer than 10% of companies that could do five years in a row with uninterrupted performance.

That led her to a third question: are there any of these businesses that have done ten years in a row, five-years and five-years back-to-back of uninterrupted growth? Remember that these 5,000 companies surveyed by McGrath have large market valuations and many are billion dollar businesses. But of the 5,000 companies she surveyed, just ten companies had done ten years in a row without interruption to their top- and bottom-line growth.

It’s significant that those companies are as “unusual suspects” as the South African set. They include Yahoo! Japan; HDFC, which is an Indian bank; FactSet, which is the US-based financial data company; Infosys, the Indian systems business; ACS, a Spanish construction firm; Tsingtao, the Chinese Brewer; Krka, which is a Slovenian pharmaceutical business.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Research in the US by Columbia Business School Professor Rita McGrath (see Box) has identified a similar, very small, very eclectic cluster of unusual companies that have achieved escape velocity. If it’s eclectic and very small, then that leaves us with a curiosity: despite their eclectic cosmetic appearance, do they perhaps have anything in common?

The answer is a simple – but resounding – “yes”. In every one of these businesses we find common behaviour and similarity in business elements. And this is where Muhammad Ali re-enters the ring. For the sake of illustration and argument, I have clustered these elements into two broad features. The one is referred to as agility and the other is absorption, both of which Ali showed on that fateful night in Kinshasa in 1974.

Agility and Absorption

Agility references the ability of a business to be innovative, to change its speed, to invent or to reinvent, to re-engineer. Changing speed is not just going faster; sometimes, indeed, it can be actually going slower. Absorption means elements which give a company the ability to withstand tough times, as we’re in now. And the absorptive elements are not just about taking punches. Absorption is also being able to come off the ropes and throw the knock-out punch when the time is right.

But can we turn words into action? It’s all good and well to say, from a competitive perspective, our strategic imperative is to be agile and absorptive. But you can’t rush back to the office or the plant and tell people, “Guys, gloves on, we’re going to be agile and absorptive!” There needs to be a practical, implementable element.

So how do we construct an agile absorber with escape velocity? How do we train our companies to become like Ali during the “Rumble in the Jungle”?

In no particular order, some of the key elements of Agility include:

Avoid Detailed Strategic Plans. These companies constantly change their minds and often in the moment. They are rapid adaptors and willing adopters. Mr Price is a good example. Think of where the company started historically - Sheet Street - and where it is today. Although the way their stores and systems might be invented and proprietary, they’re not the first people to retail clothing, sportswear or homeware. In fact, their environment is highly competitive and extremely consumer sensitive. This suggests a lot is learnt from others and borrowed from the industry, but implemented in more innovative or efficient ways.

Constant Innovation at Every Level. Investec is a good example. Many of the business that make up Investec have been crafted inside the company rather than acquired. This is about giving people running room to establish, engineer and build. In classroom language it’s called ‘intrapreneurship’. They build innovation at every level of the operation and in everyday activity.

Proximity and Engagement. WBHO shows the way in this practice. Their project managers stay on site, they are proximate and engaged, they’ve got eyes on the game and feet on the ground. Their processes support speed and they support flexibility. Also, they diversify their portfolios, so that, often, when they find something that works well they will pursue that great idea. But they won’t establish that pursuit through a grand idea, fire a cannon ball and hope it hits a target. Instead they create lots of small bets, when they find something that works they then develop that idea after proof of concept and they repeat ideas that work well.

Many Small Bets and Diversified Portfolios. Famous Brands is probably our best example of this, with EOH sitting alongside. They’re bottom-up businesses that listen carefully to their customers. The classroom language is ‘customer centricity’. Clientèle Life would also be a great example of developing products that aren’t built in the boardroom: their products are instead built and based on customer need and customer knowledge.

Federal Structures & Owner Mindset. If you are customer-centric it promotes customer stability through federal structures. So although there is a central control, risk-taking and risk management sit in the federation. Imperial is a lovely example of such a federal structure, this is a group that has been built in the fullness of time through acquisition as much as organic growth. Those acquisitions overwhelmingly have been small. If one of them doesn’t do well, it doesn’t come with the risk of pulling the business over. And each of these subsidiary businesses is run with an entrepreneurial mindset, with an owner/manager mentality. Bidvest is another great example of owner/manager mindset.

Shifting to Absorption, remember that it’s not just about taking punches…agile absorbers, companies with escape velocity, recognise that tough times come but that’s also when opportunities appear.

Prepare Reserves Accordingly. This allows them to navigate, negotiate and withstand the turbulent conditions, but it also means that they have ammunition to come off the ropes, or to go to the centre of the ring and bring a tactical energy that many of their competitors simply don’t have because of their reserves. An example of how not to do it comes from the South African mining industry where, in the late noughties, valuations got to all-time highs, helped by buoyant prices, incredibly profitable operations and very strong cash flows. Many firms even moved into the business of declaring special dividends. But when commodity prices collapsed, many firms experienced a collapse in valuation and profitability. In one example, the market cap of one of the precious metal’s giants fell by 98% and they had to go to shareholders to recapitalise as a loss-making business at the bottom of the cycle. They had left nothing in the tank. No reserves equals no absorptive capacity.

Behave Counter-cyclically. Agile absorbers – and perhaps the miner’s experience above helps reinforce this – behave counter-cyclically: in good times they shore up for bad times, and in bad times they go to the reserves and they use these to support the company, possibly do acquisitions at prices that would be more depressed than otherwise in the industry. So they’re counter-cyclical, which is contrary to “average behaviour” which obviously is pro-cyclical.

Customer-centricity. Another element of absorption, also flagged as part of agility, is customer- centricity, which promotes stability, especially in bad times. It’s a well-established fact that acquiring customers is far more expensive than retaining customers. And it’s remarkable how many businesses overlook this potential competitive strength.

Buy Yourselves. This means paying down debt and acquiring their own shares. These companies don’t use cash to necessarily acquire other businesses. Instead they acquire businesses that they know and understand: their own, which means they buy back and cancel shares.

Strong Culture. In every one of these agile absorbers you will find a celebrated culture and shared value. They eat their own cooking and walk their talk. Aspen is a lovely example of this where, in business after business, inside of Aspen, you will find a common mindset, a shared culture, an entrenched spirit and value. Investec and Bidvest are equally good examples.

Count the Cash. When it comes to measuring the performance of the business, these companies don’t measure accounting profit, they measure cash flow profit. One of the hallowed metrics is cash flow return on invested capital. This is a very sober and honest way of asking a simple question: did this investment translate into cash in the bank?

Leaders Who Stay. These business have stable leadership. Think of Asher Bohbot at EOH, Stephen Saad at Aspen and Stephen Koseff at Investec. Succession policies are communicated very clearly, and these companies also grow their own timber: they know how to attract, retain and guard talent.

These are the attributes that translate into businesses that are able to navigate and negotiate difficult circumstances in far better shape and with more impressive and stable performance than their peers. They can go toe-to-toe with tough times and get the judges’ decision every time.

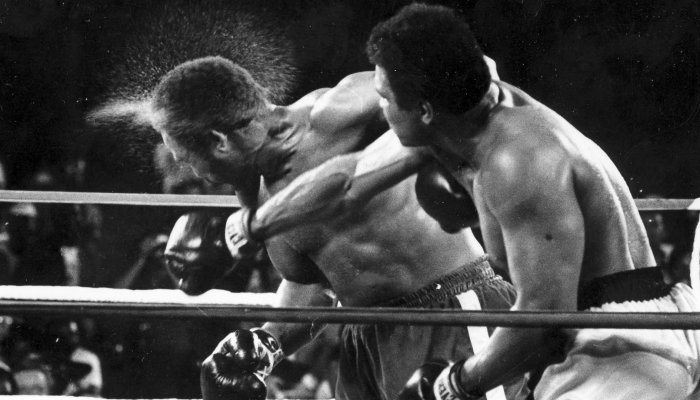

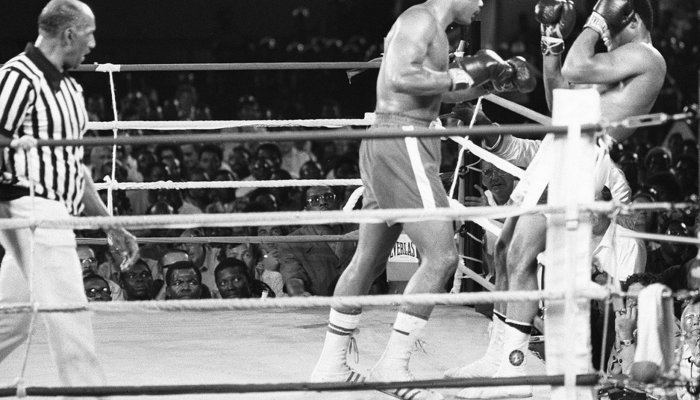

For seven rounds on that hot, humid African night, Ali had leaned back on the ropes and allowed Foreman to bring the fight to him. Punch after punch from Foreman landed on Ali’s forearms, but many slipped through his guard to hammer his ribs and kidneys. Watching replays later, it was clear that Ali had an extraordinary ability to defend. There was now no doubt that the man from Louisville, Kentucky, could absorb punishment from the hardest hitter in the world but Ali knew that throwing all those punches would expend Foreman’s energy and tire him. Ali called it his ‘rope-a-dope’ trick and as Foreman came at him, Ali also kept snaking out a wickedly punishing right jab into Foreman’s face. In round two he displayed agility, slowing his foot speed and finding in his artillery the right-hand lead, which disrupted Foreman throughout the fight. Then, in round eight, as Foreman tried once again to pin Ali to the ropes, he unleashed a devastating series of right hooks, dancing into a five-punch combination that sent Foreman stumbling to the canvas. “Big George” rose groggily on the count of ‘nine’ but his fight was over. Ali’s incredible abilities of absorption and agility had regained for him the Heavyweight Championship of the World. Not for nothing was Ali known as “The Greatest”.

[1] Zaire in 1974, now the Democratic Republic of Congo

If it were a real fight, the ref would have stopped it by now – or Zuma’s corner would have thrown in the towel!

...did this investment translate into cash in the bank?

How do we train our companies to become like Ali?