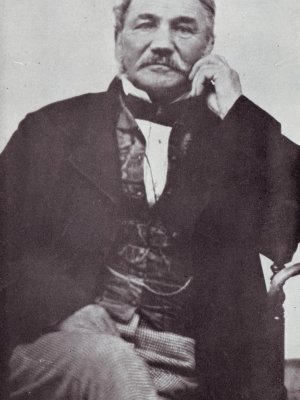

There’s also history in the bricks and concrete blocks, the iron and steel girders, the gravel and tar on the road surfaces. Study a nation’s infrastructure - the how, when and why a pass or a bridge or a dam was built - and you will receive a clear view of its economic development. Megastructures and Masterminds by civil engineer Tony Murray takes us on such a journey through South Africa, from early days of the British colonisers to a point very close to the present. He also tells the stories of the men behind these extraordinary feats, their determination and the immense challenges they faced.

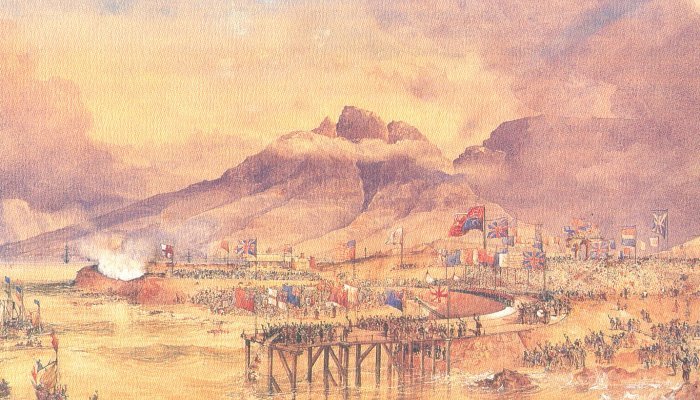

In 1828, when the Cape Colony was barely two decades old, it received a new governor, Sir Lowry Cole. “His arrival coincided with the appointment of Major Charles Michell as surveyor-general and civil engineer to the colony,” says Murray, a fortuitous pairing which produced work still in use by South Africans to this day, including the eponymous Sir Lowry’s Pass, to the east of Somerset West. Despite the obvious economic benefits of a good road to the interior, Sir Lowry himself was dragged over the coals by Whitehall for wasting funds. The Cape at that stage was a very backward and unprofitable place and the cry of “No money available!” as familiar to bureaucrats then as it still is now.

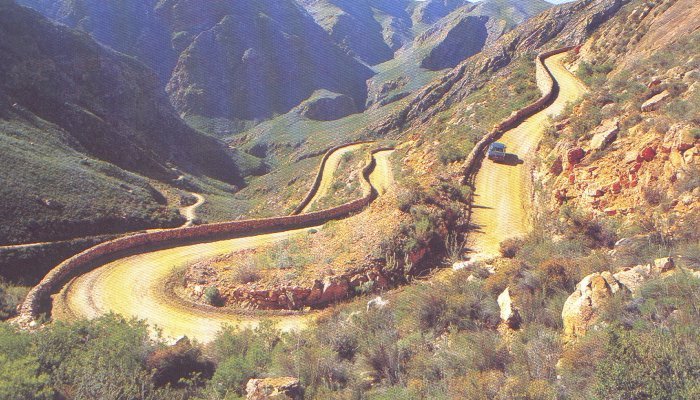

The Early Passes

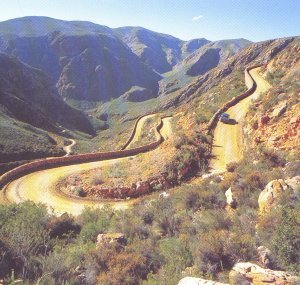

The Swartberg Pass, built by Andrew Bain's equally famous son, Thomas, in the 1880s. The coming of the railway to that part of the Great Karoo meant the economic need for the pass faded almost as soon as it had opened. Seldom used, it is therefore in more or less the same condition today as when it was originally built.

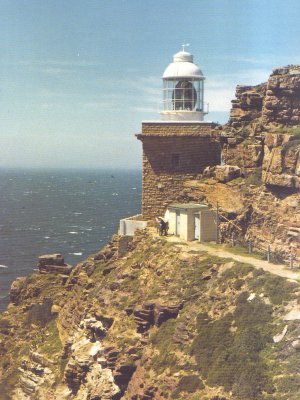

Lighthouses and Cape Town's Breakwater

Whitehall expected the Cape Colony to pay its own way, but how could it if merchant shipping was wrecked trying to pass the Cape of Storms? How could agricultural produce be exported or vessels take on - and pay for - supplies with no safe anchorage in Cape Town? The need to build both lighthouses and a safe harbour for Cape Town were constant themes for the colony's administrators and businessmen throughout most of the 1800s.

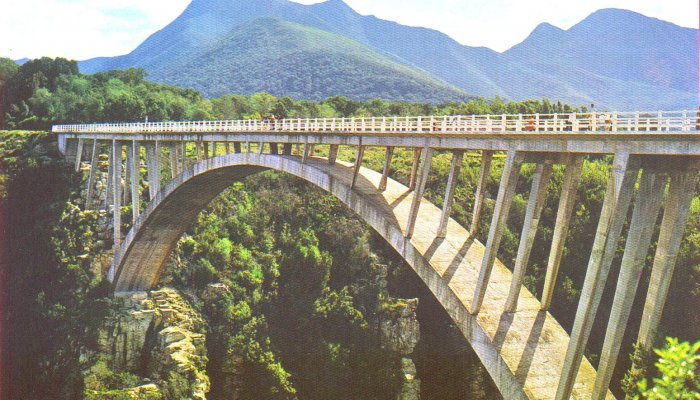

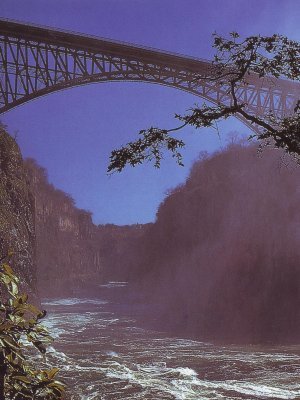

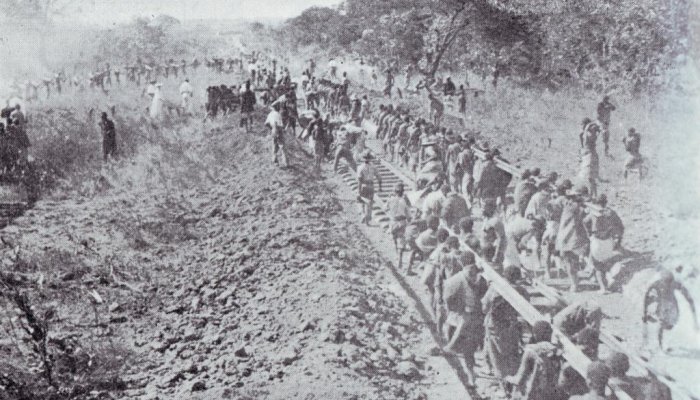

Bridges

Southern Africa's rugged terrain has posed many challenges for the great bridge and railway engineers. The ever-present need to keep costs down meant that, as with most of the passes, they were constructed on the back on convict labour. Among the most iconic is the Victoria Falls bridge, conceived as a vital stepping stone in Cecil John Rhodes' vision of a railway from the Cape to Cairo. Rhodes was dead before it was begun but it remains a masterpiece to this day.

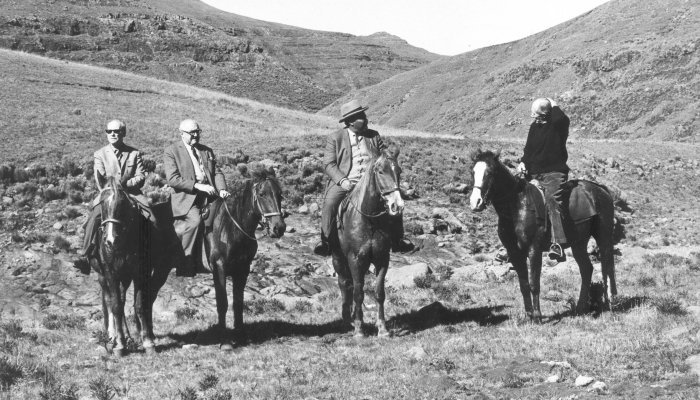

Water: Katse Dam

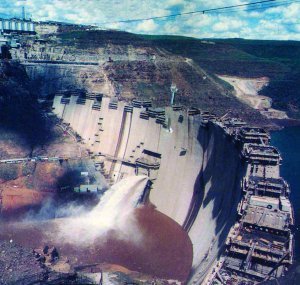

South Africa is a dry country. An expanding economy and population means its history is heavily punctuated with the search for water. Nowhere has this been more so than in the economic heartland we now call Gauteng. Today, the challenge to find additional sources of water for the growing populations of Johannesburg, Pretoria and surrounds is just as serious as when the Lesotho Highlands Water Scheme was conceived in the 1950s. Design and building of the project ran from 1953 to 1997, its centrepiece the mighty Katse Dam, a memorial to perhaps South Africa's greatest-ever civil engineer, Ninham Shand.

Megastructures and Masterminds by Tony Murray is published in paperback by Tafelberg at R250.00