As humankind faces year three of the Covid-19 pandemic, the corporate world is awash with disconnection, depression, depletion, and exhaustion resulting from the sustained pressures of remote working alongside job losses, economic hardships, fear, uncertainty, and the loss of friends and family. This has led to rising cases of burnout, so much so that management consultancy, Gallup, predicts the next global crisis will be a mental health pandemic.

The fallout of a stressed and depleted workforce has already yielded a very clear trend, one McKinsey & Company dubbed ‘the Great Resignation’. Fuelled by a shift in priorities and work-life expectations, and in some cases, the emotional exhaustion of coping through the pandemic, the Great Resignation is currently translating into record numbers of workers either quitting their jobs or actively looking for new opportunities. This trend was particularly noticeable among employees under the age of 40, the so-called millennials, whose careers had already been hurt by the 2008 global financial crisis.

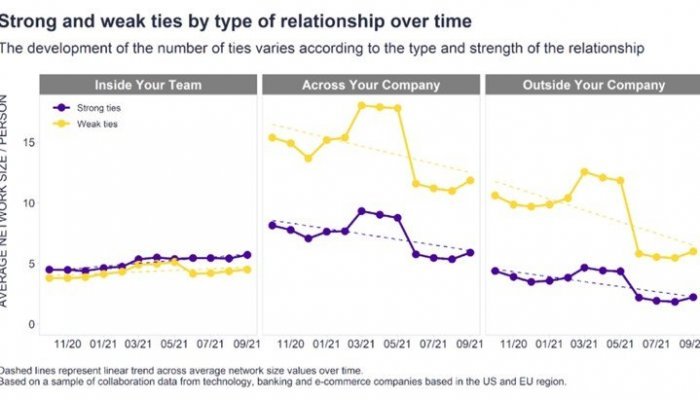

The great resignation comes with several implications for businesses, not least of which is a tendency to overwork the employees who remain and, amidst a remote or hybrid work reality, a propensity for workers to communicate less and less outside their immediate teams. A 2021 article published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, which explored the impact of remote work on internal ties within Microsoft, pointed to less collaboration, poorer information transfer and the potential to affect productivity and innovation in the long term.

This type of disengagement and overwork fuels a cycle of burnout, which feeds the Great Resignation trend. In the process, one of the essential ingredients for corporate innovation and creativity becomes collateral damage with potentially disastrous long-term implications for companies and industries.

The essential ingredients for innovation

Maxine Jaffit, the founder of Maxine Jaffit & Associates, a consultancy, and faculty member at GIBS, outlines three essential drivers that work together to create the innovation and change secret sauce. They are:

- Societal pressure and emerging norms, which unlock new playgrounds for innovation.

- Rapid technological disruption, which is currently swirling all around us in the digital economy.

- Employee value propositions, which drive employee engagement and help maintain the psychological contract with employers that encompasses ambitions, obligations, and expectations.

Of course, successful companies incorporate other considerations into their innovative management frameworks, such as training and processes, designing spaces to encourage collaboration and innovative thinking, monitoring and setting up innovation teams, ensuring a conducive organisational culture, and embedding diversity. However, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Jaffit’s trio of drivers spurred considerable change within companies worldwide as organisations pivoted out of necessity to adapt to the pandemic and the changing realities of work.

The question now, especially with the employee engagement leg wobbling, is if companies can maintain innovation once the pandemic is over.

Gillian Cross, associate director of innovation and partnerships at GIBS, says it is important not to confuse the innovation that happened during the Covid-19 pandemic as more than just a pivot. Of course, that does not mean that lessons learned around embedding innovation and developing agility, or democratising corporate culture, cannot be actively incorporated into a new future-focused approach rather than reverting to old ways.

Another aspect that needs incorporating in the future aligns with that all-important employee engagement driver: coordinated leadership and organisational accountability for issues such as pandemic fatigue and burnout. This increasingly important facet of management will, in the future, require an openness to providing better health support to employees and a deeper appreciation that the positive impact of doing so will support the sustainable development of the organisation.

Mental health and well-being: the next frontier

Until recently, mental health did not feature as an essential component in driving innovation, but post-Covid, it certainly will be.

Jaffit says the pandemic has brought into stark focus “the absence of care and concern for mental well-being globally”. One only has to consider the response to tennis player Naomi Osaka’s withdrawal from the French Open in 2021 and her disclosure that she had “long bouts of depression”, or swimmer Michael Phelps’ battle against anxiety and depression, and Olympic gymnast Simone Biles’ withdrawal from events at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics to appreciate how divided responses are to issues of mental health. Covid-19 brought these concerns into the mainstream.

This is evidenced by the rise in mental health start-ups. “There are now seven documented mental health unicorns in the tech sector,” says Jaffit, compared to just two in 2020. These include Genoa (telepsychiatry), Lyra Health (telehealth), Calm (mindfulness and meditation) and Talkspace (teletherapy).

“The downstream impact is that more employees are voicing their concerns and needs around mental health and overall well-being,” says Jaffit. “Around the world, the human has come to the fore.”

This, in turn, requires a different approach to management – one that is empathetic, adaptive and able to cope with the newfound flexibility and wellness needs of employees. Changing the way businesses lead and operate might also be the missing ingredient for stoking innovation both during and after a global crisis.

Insights into innovating through pandemic burnout

Throughout 2020 and 2021, the GIBS corporate education team saw their clients battling but also embracing the change and innovation required of them. Recognising the pressure that back-to-back online meetings were having on staff, one of GIBS’ financial services clients started ‘step-down Wednesdays’ whereby no meetings were allowed and the day was allocated to learning.

With another client, what started as an intervention to roll out healthy teamwork practices turned into a larger intervention around organisational culture. This was a company that accepted weekend work, late-night calls and 24/7 availability. Had they not changed, any attempt to embed healthy human processes and the psychological safety employees need to openly express opinions and collaborate freely and effectively would have failed.

“I think psychological safety is intrinsically important to innovation,” stresses Cross. “After all, if you’re coming up with good ideas and trying to innovate, but your culture is very risk-averse and doesn’t support that, you will shut down.”

With clients like Aspen Pharmacare and Anglo American, the GIBS corporate education team has already moved from content design to experience design and from providing content to curating content, explains Angelique Mare, senior manager of learning design. This, in itself, is a radical departure from previous interventions and one that fosters interaction and collaboration.

“With Aspen, we’ve worked with faculty to create programmes that we can reuse,” explains Mare, highlighting the use of pre-recorded video content which is a more effective use of both faculty and delegate time as it allows delegates to work through the content at their own pace within set timeframes. This approach also ensures that real-time sessions with GIBS experts are more in-depth and practically orientated. “It’s in these conversations that we’ve seen the biggest value,” says Mare, adding that peer-to-peer engagements are also essential as they give participants the opportunity to hear, share and learn from one another. This creates a foundation for innovation and creative collaboration.

GIBS has also actively innovated in line with client needs and taken cognisance of a desire for shorter interventions, more deliberate insights from faculty members, and more time spent on the practical application of theory, explains Mare. As the team learns, it tests new approaches and incorporates these changes and learnings into future programmes.

Similarly, the GIBS Fellowship Friday gatherings, which were inspired by Cross at the start of the pandemic, continue to provide a safe space for GIBS clients – many of whom hold human capital portfolios – to come together and make sense of many issues they were dealing with during the pandemic through a mixture of peer input and expert advice.

Jaffit, whose area of practice is in adaptive systems, particularly in the area of adaptive change or mindset change, ran a three-part adaptive leadership series together with her Australia-based colleague, Terri Soller, as part of Fellowship Friday. The intention behind the series was to offer guidance on how to collaborate and how workflows have changed in a digital, physically distanced world. The insights gained from this interactive process ultimately led to the creation of the GIBS Creating Healthy, Hybrid Work Practices programme. Mare explains that the guide helps companies embrace the importance of “surviving and thriving” in complex systems by embracing “experimenting and experimentation”. After all, the road to innovative output is pathed with the ongoing testing and tweaking of ideas and inventions.

This essential part of the innovation process simply cannot be achieved with a fixed and unyielding mindset, stresses Jaffit, adding that the one thing that the pandemic did was “make fearful people even more fearful, even fearful to try anything”, and this inevitably puts the brakes on innovation.

Fortunately, the tools for dealing with complexity are readily available to all, says Jaffit. “My doctoral research is on adaptive resilience, and I asked why certain companies transformed in the year of Covid-19 and what it is about certain organisations that they have this innate capacity not only to bounce back – which is resilience – but to bounce forward, to transform, and redefine themselves.”

She adds: “My hypothesis is that organisations with this capacity constitute resilience in how they talk and how they make sense. And they are not so attached to their identity that they are not willing to actually redefine who they are. Their history isn’t stronger than the present.”

And, in the process of redefining themselves, they keep the drivers of innovation alive.

What is burnout?

Dating back to the 1970s, when American psychologist, Herbert Freudenberger, coined the term ‘burnout’ to describe the significant stress faced by the likes of doctors, nurses and caregivers, burnout has recently taken on widespread work-related overtones.

Typically, burnout is said to encompass symptoms such as emotional exhaustion, fatigue, frustration, cynicism, numbness, listlessness, and reduced creativity.

From January 2022, the third year of the Covid-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (11th revision) included burnout for the first time as an occupational phenomenon “resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”.

Burnout and the boss

If the role of managers and leaders is changing, so, too, must the approach to management education, says Gillian Cross.

Drawing on forecasts from I.T. research house, Gartner, Cross notes that “the boss won’t be missed” in the future world of work. “According to Gartner, less than 50% of employees believe their manager can lead their team to success in the future, mostly due to their lack of management skills in a remote or hybrid environment. By 2024, 30% of corporate teams would be without a boss, Gartner forecasts. So what we’re moving towards is peer-based collaboration and management,” says Cross.

Drawing on insights she and Cross gained by researching tech companies in the US, Maxine Jaffit adds: “In the future, there will be a need for managers, but their role is changing from a traditional role. Managers are becoming curators of learning and experiences for their people. So, everything we’ve taught and everything we’ve been learning is no longer useful.”

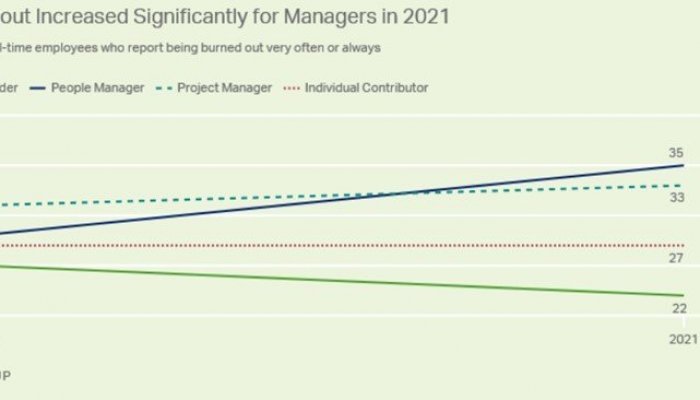

Given these radical shifts, it’s hardly surprising that managers are among the worst affected when it comes to burnout. Gallup surveys show that in 2021 burnout increased notably among managers.

Part of the burnout and stress for managers worldwide stems from a deep knowing that what they are doing is no longer enough for the organisation, its new ways of working and the needs of employees, explains Jaffit.

“Managers want to keep their jobs and be relevant, and they want to move up this so-called ladder, but the rungs have changed,” she says.

Angelique Mare

Angelique is a senior blended learning solutions manager in the corporate education department at GIBS. She has over 12-years of corporate learning and development experience in the finance industry, specialising in the design, development, and delivery of learning programmes. Mare boasts a decade of leadership development experience at GIBS, having designed and delivered several successful leadership development programmes across leadership levels and disciplines for leading organisations in the mining, banking, IT and telecommunications, and FMCG sectors.

Gillian Cross

As the associate director for innovation and partnerships, Cross leads a team that initiates new partnerships, products, services, business models and ways of configuring value that differentiate GIBS in the markets in which they operate. With over 30 years of experience in designing engaging ways to develop world-class leaders from pre-manager to C-suite, her strengths lie in her ability to lead and inspire multi-functional teams to design and deliver the best possible result.

Maxine Jaffit

During her 30-year career, Jaffit has consulted to organisations in South Africa and the US, from Investec Bank, Discovery and Nando’s Worldwide to Google. Her work focuses on unlocking human and organisational potential to navigate complexity and build more open, resilient, and wise organisations. As faculty at GIBS, Nando’s Worldwide teaches and supervises students on the MBA and the PDBA. In her coaching practice, Jaffit employs an integrated, multi-disciplinary approach to unleash leadership potential and achieve optimum positive, sustainable change.