Steinhoff. Tongaat Hulett. Oakbay Investments. Tegeta Exploration and Resources. VBS Bank. EOH. Bosasa. MultiChoice and ANN7. KPMG and the rogue spy unit. McKinsey and Trillian Capital Partners. Like a veritable rogues’ gallery, these business and accounting scandals have rocked the accounting profession, raising ethical concerns and focusing the profession’s attention on ways to improve its ethical standing in business and society.

As the main accounting body in the country, the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) stands at the forefront of this effort. The SAICA Code of Professional Conduct spells out the responsibilities, safeguards and fundamental principles of the industry and holds members to account. In addition, explains Gideon Pogrund, director of the GIBS Centre for Business Ethics, “SAICA has an integrated ethics plan, which is about restoring reputation and trust in a profession which has been seriously damaged.”

Recognising that accountants play an important role in ethics and governance and that SAICA members are among the essential guardians of governance, the body approached GIBS in 2020 to undertake a three-pronged Ethics Barometer industry survey to examine the similarities and differences in approach to ethical behaviour between trainees, students and professional members. The GIBS Ethics Barometer SAICA Trainee Report is the first in the series.

Focusing on ethics, explains Chantyl Mulder, executive director: learning, development and national imperatives at SAICA, is particularly important for SAICA. The first survey with trainees kickstarted a process of ‘pressure checking’ the industry’s pipeline, from students to professionals.

“Ethics are embedded in the fundamental principles that underpin what it means to be a chartered accountant,” she says. “The chartered accountancy profession has unfortunately been the focus of much negative media over the past few years due to members not acting in a manner befitting the designation of CA(SA). The Ethics Barometer is allowing us to take a hard look at ourselves and at the profession, and from this to take further action to address the issues.”

The core insights

After careful analysis, seven key themes were drawn from the SAICA Trainee Report research.

1. Alignment with the SAICA code

Five key principles underpin the SAICA Code of Professional Conduct: Honesty, responsibility, capability, self-control and ambition. The study showed that trainees who participated in the research were largely familiar with the code (93%). In addition, it closely aligned to their personal values and was often used as a guideline for decision-making (88%).

This alignment of personal values to the SAICA code was noted with interest. “Alignment of values is helpful as values drive attitudes and behaviour, which means that the vested interest for the individual will align to the profession’s interests,” says Mulder. “I am curious to see if the alignment is similar in the member survey.”

Encouragingly, trainees generally felt that accounting professionals lived up to the SAICA code concerning integrity (73%), professional confidence and due care (77%), confidentiality (82%), and professional behaviour (73%). However, the results for the principle of ‘objectivity’ – at 69% – were outside of the Ethics Barometer’s ‘ideal range’.

On this ‘objectivity’ point, SAICA noted, “The feedback is very valid. This is an area that has received significant attention, especially from the IRBA [Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors] over the past few years and is a key concern behind enforced auditor rotation.”

2. Prevalence of accounting misconduct

When trainees were asked about the type of misconduct witnessed over a 24-month period, from a list of 16 possible types, three dominated: Phantom ticking (40%), knowingly omitting or obscuring information to mislead (30%) and late reporting (25%).

Phantom ticking, or ghost ticking – relating to documenting audit procedures that were never completed – was reported less than half of the times it was observed, raising a question about why trainees could identify these instances of misconduct but rarely reported them. The suggested interpretation was that trainees “feel uncomfortable speaking out about misconduct for fear of being victimised or ignored. In turn, this reflects a theme identified in the broader Ethics Barometer – a pervasive lack of trust among South African employees.”

Of particular interest to SAICA, as the next two surveys are rolled out, will be to see how trainee insights correlate with the other two groups. “This perspective of the trainee is very valuable, but in some instances, we require more information to distinguish perception, which is an opportunity to educate and provide more transparent training, versus fact, which requires action relating to unethical behaviour,” Mulder explains.

3. Public image of the profession

The way the profession is portrayed in the media is something trainees are sensitive to, which impacts their perception of the accounting profession. The research highlighted two issues. The first examined the future attractiveness of the career in light of bad press, and the second focused on the important views of the ‘vocal minority’, who may not represent the majority view but who express their views openly.

This moral courage to speak up, coupled with action to address unethical behaviour, is key to improving ethical behaviour. “In the training environment, where trainees are passionate about speaking up but find themselves in an environment where this is not encouraged, this reinforces the development of inappropriate behaviour at the outset,” says Mulder. “If this is discouraged at trainee level, how are we to grow professionals who behave in the manner expected?”

4. The sector is broadly ‘ethically fit’

When comparing the SAICA trainee findings to the benchmark average of the 2019 Ethics Barometer, the accounting profession was regarded as operating at a higher level of ethical performance than is the norm in corporate South Africa. But, again, the results of the subsequent surveys will make for an interesting comparison.

Despite the above-average performance on this point, Mulder says: “It is helpful to know how we are doing compared to other companies, but we also need to hold ourselves to a higher standard than the average company – ethics is fundamental to the accountancy profession. We must be careful not to pat ourselves on the back just yet.”

5. Shoddy treatment of trainees

Less positive was the way trainees felt they were being treated by their employers. The report said, “They are overworked and underpaid; they are not valued and are often bullied; their employers do not keep their promises, and they are not encouraged to speak up. Perhaps most frustratingly, trainees feel trapped by their commitment to employers to complete their training.”

As one participant noted, “As audit trainees, I do feel like we are overworked and underpaid. Audit firms know that we need them in order to qualify, so they work us to the bone. At times I don’t think that it is humane or healthy to work the hours that we do.”

6. Committed to transformation

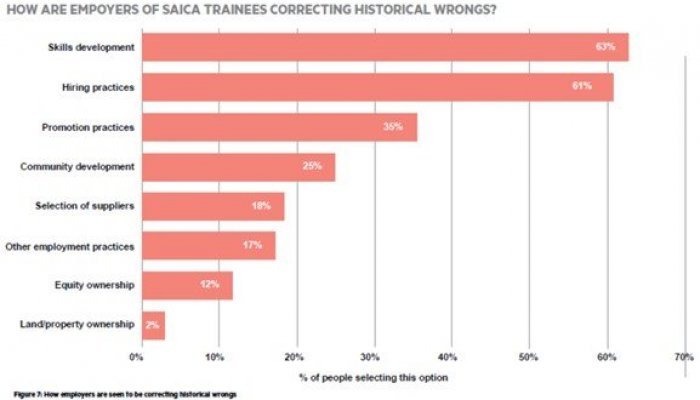

Generally, trainees looked at their employer’s commitment to transformation favourably, with 48% agreeing that understanding the need for change was driving actions. Some 28% strongly agreed, 17% were neutral, and 5% disagreed. Just 2% strongly disagreed.

Transformation is a key strategic objective of SAICA, says Mulder. “We have a unit dedicated to transformation and growth, and this objective touches on all legs of the qualification route from the high school learner, to student, to trainee and exam candidate.”

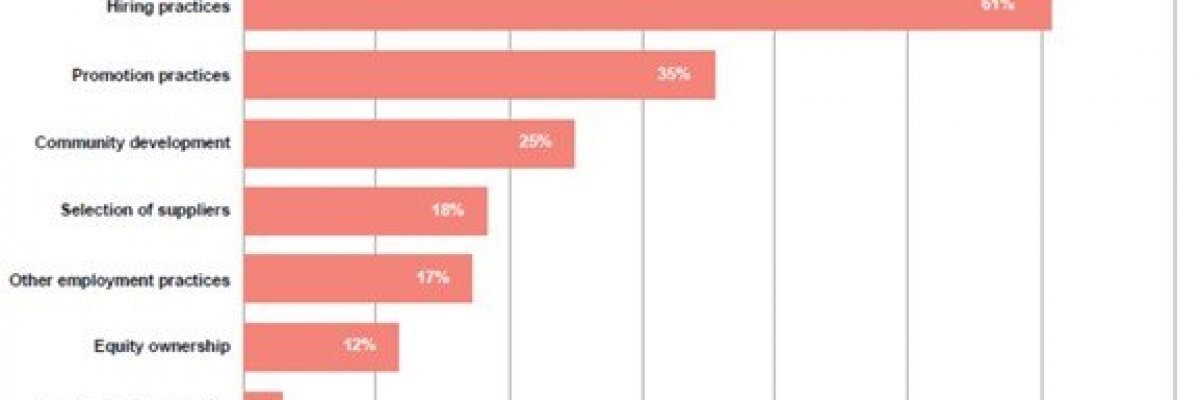

While this commitment was largely seen as sincere, actions weren’t always effective in driving transformation. Trainees felt more could be done, community-based engagements could be undertaken, and equity ownership could be more strongly addressed.

7. See no evil…

Trainees were less likely to report misconduct for fear of bullying and intimidation, which highlights that unethical behaviour is often “seen but not heard”. Addressing this was seen as a priority by SAICA.

“We have taken a number of steps to open up direct communication with trainees, address myths regarding the training contract and trainee rights and obligations, and generally improve the direct relationship with trainees,” says Mulder. “This has resulted in trainees approaching SAICA more readily with challenges they experience, enabling us to take action more swiftly. We are also improving at linking trainee concerns received outside of the monitoring process to our accreditation visit process.”

The red flags

The report also highlighted several potential areas of concern for SAICA and the profession, including complaints of bullying and intimidation, the expectation of having to work unreasonably long hours without recognition or compensation, and reticence on the part of trainees to report incidences of misconduct. The latter point, noted the report, “suggests a need for the development of ‘cultures of dissent’ so that trainees experience the institutional and psychological safety they need to be able to speak out.”

These linked back to the broader issue of corporate culture (including unfair promotion practices and pay scales) and employee engagements that fostered a speak-up culture.

At a professional level, worrying insights related to views around the willingness of the profession to deal with scandals and, indeed, the ability to repair the damage done to the collective reputation. Digging deeper into day-to-day deficits around ethical behaviour in firms, the general “erosion of the objectivity that is a hallmark of good accounting practice” was worrying.

For SAICA, the most pressing issues, which were already receiving urgent attention from the training team, were excessive overtime impacts and creating an environment where trainees could speak up without fear of victimisation.

Elaborating on the last point, Mulder explained that, “This is also receiving specific attention through the revised accreditation criterion relating to ethics. At the end of 2020, we changed one of the accreditation criteria in the training regulations to specifically address organisational culture and practices relating to ethics. The accreditation criteria underpin our monitoring and accreditation activities so non-compliance impacts the training offices risk rating and accreditation. We have also provided support to training offices to understand what is expected and look at ways of addressing gaps.”

Calling the first in the three-survey series a ‘wake-up call’, Mulder admits, “I don’t think the results come as a surprise”. However, what is encouraging about SAICA’s approach, says Pogrund, is that they “have a bold plan to share these insights” and use the knowledge gained to refocus their efforts to uphold ethical conduct across the profession.

The ins and outs of execution

In consultation with SAICA, the GIBS Centre for Business Ethics created a survey questionnaire that measured the 68 behaviours and six constructs covered by the GIBS Ethics Barometer assessment tool and then added three accounting-specific constructs:

- Awareness of the SAICA Code of Professional Conduct and the code’s influence on behaviour and its alignment with personal values.

- Topical issues relating to the accounting profession.

- Avoidance of accounting misconduct.

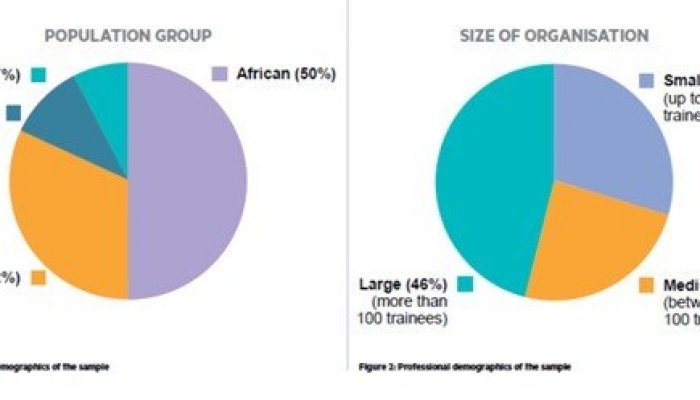

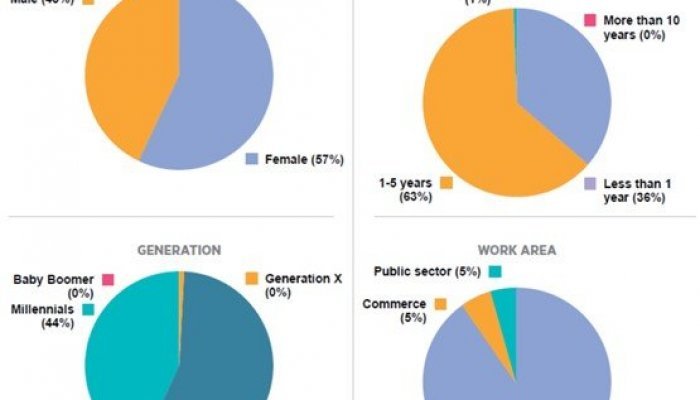

The first phase of the SAICA research, focusing on the trainee group, approached 12,000 individuals on the SAICA database, of which 2,083 opened the survey link. In total, 1,672 completed responses were received as part of the quantitative aspect of the study, while 3,146 verbatim responses to open-ended questions were analysed as part of the qualitative aspect. The demographic and professional breakdowns of the respondents are outlined in the accompanying pie graphs.