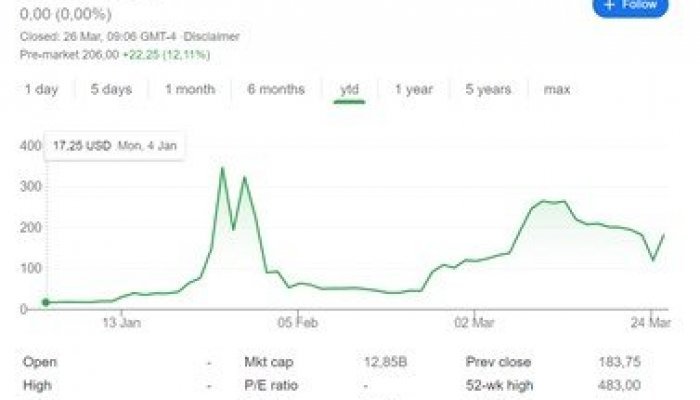

It is not your grandfather’s economics! In January 2021, that scenario played itself out to the shock and awe of market watchers. Several hedge funds had, in fact, “shorted” GameStop. That was reasonable. Shorting the stock meant they would gain from the share price falling. And since GameStop is a bricks-and-mortar seller of video games, a product increasingly housed in the cloud, betting it would go the way of Blockbuster and the dodo seemed reasonable. At least, that’s what fundamentals said.

The trouble is, as Tyrion Lannister of Game of Thrones fame argues most eloquently, “There is nothing in this world more powerful than a good story”. The story conjured up and shared like wildfire on Reddit went something like: “The baby boomers have screwed us for long enough, left us serving coffee while applying for jobs and paying off student debts, but now we have the numbers and the technology to get one back on them!” At least that is one version of the story.

Several participants in the eight-million-follower strong r/wallstreetbets group told it more emotively. “You’re a firm which makes money off of exploiting a company and manipulating markets and media to your advantage,” said one user, directing the comment at one of the prominent short-selling hedge funds involved. “I dumped my savings into GME [GameStop’s trading symbol], paid my rent for this month with my credit card, and dumped my rent money into more GME. This is personal for me and millions of others. I’m making this as painful as I can for you,” seethed another.

Supply and demand did the rest. As word spread, more and more amateur investors bought stock, driving the price up, hoping to buy on the rise. Even the short-sellers had to join in. To cover their losses, they were forced to buy stock, too, further fuelling the mania in a textbook case of a short squeeze. The GameStop share price on the New York Stock Exchange rocketed some 1,500% in a couple of weeks in January.

Of course, nothing had changed about the company itself. There was no highly anticipated acquisition, no release of new technology or shining results. The tools of valuation every business undergraduate learns were rendered temporarily paralysed. The most thorough discounted cash flow analysis or sharpest ratio was blindsided by a story shared on a social media community renowned for the creative use and invention of curse words.

Great economist, John Maynard Keynes, had crystallised the phenomenon of investors moving like herds, animated not by fundamentals but spurred to action by emotion. But how would one possibly go about measuring or analysing these “animal spirits”? Until recently, it was anybody’s guess. This was the world of following one’s gut like a sixth sense. Exponents of this tend to learn the hard way how unreliable it is. However, three bodies of thought only properly explored over the last five years provide tools to make sense of investing in an age where markets are swung by a Tweet.

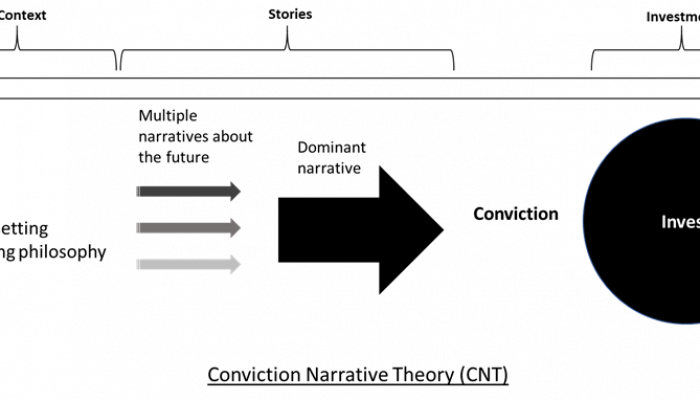

First, emerging largely out of the University College London’s Centre for the Study of Decision-Making Uncertainty, is a paradigm of investing seated in the heart of what makes us human. Prof. David Tuckett, a psychoanalyst by training, built the conviction narrative theory (CNT) based on 52 interviews he conducted with major hedge fund managers. As each explained, the way he or she made capital allocation decisions, and despite as many investing philosophies as there were interviewees, there was one constant: each described a storytelling process. From the most calculating ‘quant’ investor to the most personable characters who “invest in people”, this held true.

Whether relating the shape of a yield curve to bond price changes, justifying faith placed in a youthful management team or boasting about a trade that had accounted for some complex market phenomenon nobody else had seen, the “currency of decision-making,” as Tuckett puts it, was narrative. “To understand the way financial assets are valued, we must realise that, in essence, what is being traded are stories – competing imaginative accounts,” he goes on.

Indeed, when we buy a share, we aren’t buying the inventory and equipment the company owns. We are buying into a reasoned hypothesis about the future. At its most basic, “this company’s revenues will probably grow roughly as fast as inflation for the foreseeable future”. Or, as was the case with the GameStop scenario, something far more complex.

Under the narrative model, our charts and financial reports and fancy algorithms remain relevant. But they are subjugated to the position of data points in a larger process. They are fuel for our educated imaginations. Whether mulling pension options with a spouse or debating a major capital expenditure with an investing team, the decision-making process looks remarkably similar. One person shares a reasoned hypothesis about potential events and when they might happen. Someone else accepts one or more premises, rejects others, and offers a new line to the plot. And so it goes on. We narrate our way towards a dominant narrative. Not one with a specific net present value or some acceptable risk-return ratio, but one that is good enough to provide us with conviction to act. A conviction narrative.

Conviction narrative thinking helps to understand the decision-making process investors went through. It doesn’t directly address the macroeconomic phenomenon of narratives moving market prices wholesale. If we zoom out to this level of abstraction, another novel lens becomes useful. It was 2017 in his presidential address to the American Economic Association when Bob Shiller gave a major platform to what he calls ‘narrative economics’. Pithily, the Nobel Prize-winning economist and Yale professor called for “a new form of economics that takes narratives seriously”.

Shiller’s approach acknowledges that popular stories drive asset prices. If I’m discussing Bitcoin, and you’re discussing Bitcoin, we can be sure that hundreds of millions of people around the world are also discussing Bitcoin. The same goes for everything from asset classes to TV shows. And it is this vast, partly invisible force of shared stories that combine to drive demand.

Very well. That begs the question: how on Earth do we measure the accumulation of small stories shared in myriad ways almost ceaselessly around the world? As it happens, we use a science we’ve all endured a crash course in starting circa January 2020. Stories are shared person to person, amplified by large gatherings (virtual or in-person), and, in the right circumstances, go viral with rapid exponential growth. In a world where we increasingly share our thoughts online, we can map this process with tools developed by epidemiologists to analyse viruses like Covid-19.

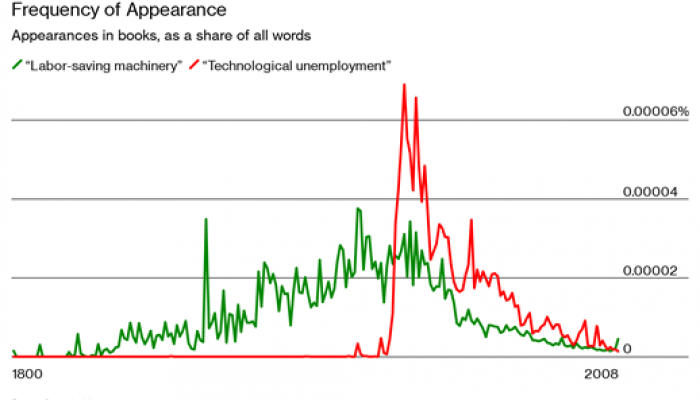

By way of a simple example, consider Shiller’s Google Ngrams search for terms that describe technology replacing the jobs that people do. The exact terminology varies over time, of course, but the fear – the narrative itself – is an old one. We worried “labour-saving machines” like mechanical looms would make clothing workers redundant centuries before “technological unemployment” by way of machine learning and robotic process automation became canteen chatter.

Work out of David Tuckett’s UCL lab has demonstrated one of the many potential uses for this approach. Analysing text from Reuters’ databases, researchers have been able to extract economic sentiment. This has enabled them to quantify “two classes of emotion in narratives – those prompting either excitement about gain or anxiety about loss”. Experiments applying an algorithm that identifies at breakneck speed shifts between these emotional groups have vast economic forecasting potential and more.

The irony is that these narratives are analysed by hardcore numerical modelling. As Shiller puts it, “serious quantitative analysis of changing popular narratives”. But the nexus of narratives and numbers is increasingly important. If we are to navigate this new world of steroid-pumped narrative and big data, this is a space we all need to get comfortable with – word nerds and number geeks alike.

Self-confessed “numbers guy”, Professor Aswath Damodaran, provides solace that anyone can overcome their unique numero-literary pigeonholing. More than solace, he provides practical tools to help value a company with suitable weight on numbers and narratives. The so-called “Jeddi of Valuations” teaches at New York University’s Stern School of Business and reaches many more through his popular blog and YouTube channel.

Damodaran makes a distinction that is critical to understanding the GameStop squeeze. “Valuing an asset is not the same as pricing an asset,” he emphasises. “We know what drives the value of an asset. It is expected cash flows, the growth of those cash flows and the risk of those cash flows. I’m not giving away any secrets when I say that.” Very little happened to those three elements for GameStop during those eventful weeks of January. So, what caused the price to deviate so wildly from value?

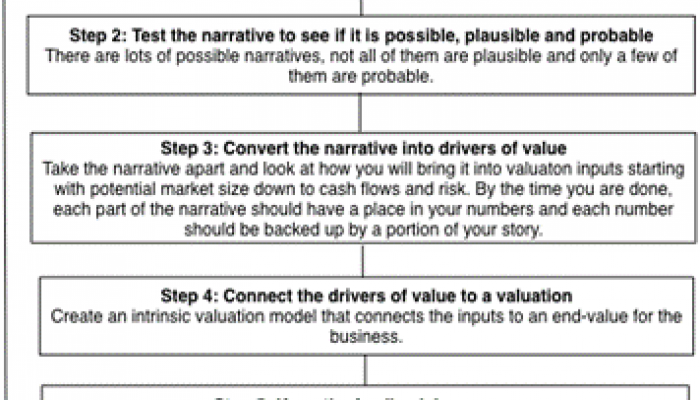

“Every good valuation starts with a story. And that story has to find its way into the numbers,” Damodaran teaches. “Each part of the narrative should have a place in your numbers, and each number should be backed by a portion of your story”. That is, every time you plug a number into your spreadsheet, check yourself with a story.

Damodaran’s five basic steps to valuation give investors a framework with which to form views both on a stock’s “real” value and its market price by varying the narrative input.

So, with the clarity of hindsight, a dash of imagination and the help of our three investing experts, the next “GameStop” might be a very different story. Consider a leading role for the algorithm that flags a nascent emotional trend, supported by a brave sidekick who crafts the winning ‘buy narrative’ with a cameo by the sage who finds long-term value in the nexus between numbers and narratives.