It felt like a silly question. I had done my reading and was here to write a serious case study about Zimbabwe’s monetary crisis. But I hadn’t found a moment to check for myself, so asked: “When you draw money, what currency is actually in the ATMs?” Tendai [not his real name], my colleague and guide to his home country for this three-day research mission to Harare, made no effort to hide a chuckle. He didn’t have time – it was more a reflex. “Nothing,” he said. “There’s nothing in the ATMs!” I smiled at my own naïveté as we continued our dash along Samora Machel Avenue in Tendai’s little Toyota hatchback to our next interview. I had a lot to learn.

If arriving at the airport still named for the decades-long but recently deposed leader who had ruined the country was more annoying than offensive, what greets the eye on the short drive to the city brings home very rapidly the horror of the situation. Dotted alongside the highway are figures spread out for hundreds of metres on each side, hoeing, picking and planting. But they aren’t farmers. They’ve pegged off a patch of earth no bigger than a comfortable lounge to grow crops. Zimbabwe posted a bumper crop in 2017, but not from operations like this.

...people were out and about, delivering goods, going to work and attending meetings.

Business happens

It was partly this backdrop of economic mystery that had brought us to Zimbabwe. The big moves are reported by the media and analysed by conventional economic thinking. We know commodity export figures, official government policy and (often regrettably) what people say on social media. But with not-always-honest administrations and extreme conditions, the best route to quality information is usually speaking to people on the ground who are doing business and adapting in real time as the system shifts.

Additionally, in his work brokering infrastructure deals in Zimbabwe, Tendai had encountered a surprising degree of success. Yes, plenty of failures and enterprises that chug along, surviving on small wins in between spells of paralysis. But also genuine, sustainable success. How had some people and businesses won in this market through land seizures, hyperinflation, deflation, regime change and more while all about them were losing? We prepared a set of questions and lined up half a dozen interviews for our quest.

It was already hot when my transfer dropped me at Monomatapa Hotel in central Harare just before 9am. I was struck by how many hotels and key institutions of state were aggregated along one street. Within a kilometre, along Samora Machel Avenue, were the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, the Zimbabwe Energy Regulatory Authority, the country’s highest courts, the Office of the President and Cabinet and almost a dozen banks. The South African in me wondered why Nelson Mandela Street was positioned far less salubriously two roads down. It must also have been my instincts that had me nervously holding my pockets while on a quick walkabout. Over the next 48 hours I would gradually come to feel far safer than I do on the streets of my neighbourhood in Johannesburg – another mystery of this economy.

Tendai arrived and we were buzzing through busy streets to our first interview. The tripling of fuel prices wouldn’t happen for another couple of months, but I had expected quieter roads. Granted, some of the traffic took the form of stationary vehicles queueing for petrol, and a rarity of operational traffic lights didn’t help, but people were out and about, delivering goods, going to work and attending meetings.

The Banker

Our first interview was valuable for reasons unanticipated. It uncovered a strange phenomenon of meetings in Chinese restaurants. Zimbabwe hardly strikes one as a hub of Asian culinary sophistication, but two of our meetings were scheduled for what appeared to be Chinese restaurant-cum-casinos. This one appeared to have a hotel segment, although no sign of guests was apparent to justify the ornately set tables and the smell of lunch.

Our meeting was with the former CEO of one of the largest banks that had folded in Zimbabwe. Tendai described him as somewhat of a maverick in his day. “These are the sorts of guys who lived the Wall Street high life in the late 1990s to early 2000s,” he had told me during our planning of the trip. “Back then the banks were trading all sorts of things, including the sophisticated securities that led to the implosion of the sector in 2003.”

Things have changed. We were ushered by an assistant into a small room with a big safe and a rotund man. The brevity of this section indicates its tangential relevance to answering our questions, not that it was boring. It was the story of a banker who had easy lines of credit with his choice of global finance houses, until one by one they severed ties with a country entering pariahdom.

The Investor

That afternoon we made our way to the leafy suburb of Alexandra Park, home to the Harare Botanical Gardens and our next interviewee. This revealed another workplace trend. It seems businesses have largely abandoned the city centre and set up shop in what were once quite palatial family homes.

This time we had secured time with the relentlessly sharp mind of Dzika Danha. Born in Zimbabwe, he studied finance and banking at the London School of Economics and the University of London. His beautifully clipped British accent was honed well before that as a public schoolboy in Dorset. Having helped build Renaissance Capital’s Africa business, Danha left in 2010 to co-found IH Group, where he is now managing director.

An hour was not enough. Perhaps most salient to this story was Danha’s take on how we got to where we are. While Zimbabwe has been almost perpetually in crisis for decades, he has no trouble articulating the precise cause of the current monetary milieu. “A lot of people think it was the bond notes,” explains Danha. “If you listen to the Twitter community that’s what you’ll hear. It’s not true…”

We were ushered by an assistant into a small room with a big safe and a rotund man.

“The genesis of the situation we are in today was in 2016 with the recapitalisation of the Reserve Bank. A whole lot of gold exporters were owed outstanding money by the bank. That is, they were owed real [US] dollars from exports. The bank began giving them TBs [Treasury bills], issuing them at parity, 1-to-1 with the dollar. The sum was something like $2bn.

“Now, let’s say you’re an exporter who can take money out of the country. The Reserve Bank tries to compensate you for dollar-denominated legacy debts with TBs that it has printed. You’re going to discount your TB, sell it for USD and whoosh, all this hard currency leaves the country. Suddenly we have a rate between US dollars and the local money.

“The bond notes were largely irrelevant. In fact, they were quite clever when they were conceived. They were meant to replace USD as a medium of exchange so that government could capture the USD in the system.”

The Businessman

In Danha we had found our oracle for economic insights. But his world is analysis, advice and high finance. Tendai and I needed a different sort of operator to explore the wizardry of on-the-ground operational success in Zimbabwe. Someone whose name ended in CA (Z), CA (SA), CFA, with experience in private equity, greenfield and brownfield investment, managing the local dealership for a global brand and chairing the board of a Zimbabwe Stock Exchange-listed entity would be ideal.

...one of Zimplow’s top performers is Mealie Brand, which makes and sells ox-drawn ploughs...

Thomas Chataika CA (Z), CA (SA), CFA is the managing director of asset manager Invesci and chairs Zimplow, a maker and distributor of farming and mining equipment, with a stake in local dealerships for the likes of Caterpillar and Massey Ferguson. His stance: “The monetary madness in Zim represents opportunity to me.” We had found our man.

“I don’t like what it does to the country,” says Chataika, “but as a businessman, I love this current impasse where foreign investors aren’t coming in. You’ve got to use the opportunity.”

Part of the strategy he describes demands a nuanced understanding of the store of value in Zimbabwe and how it changes. “If you’re a local guy, you’ve got to stay on top of pricing on a daily basis,” he continues. “To October [2018] we sold 180 Massey Ferguson tractors. That’s up from 97 last year. The reason is that when the currency started to go up and down, guys panicked and looked for ways to secure their buying power – so they bought things. You’re pulling future demand into today. It’s very profitable if you have stock. So you need to manage your balance sheet. The same principle applies to shares. One of the things we’ve instituted at Zimplow is a share buyback. Shares are currency as long as I’m running a good business. Zim has a shortage of investable assets.”

Industry choice is just as critical. Chataika describes how even through hyperinflation, when everyone else is suffering, there are always people exporting diamonds and platinum, pulling in hard currency. “Even if it’s tough, what matters is that you remain a going concern and make your money in the right currency,” he goes on. “When you come out of a rough time with a going concern, it can be very profitable because you can slap on another 10% to your profit margin because so few people can navigate the terrain.”

It seems instructive that one of Zimplow’s top performers is Mealie Brand, which makes and sells ox-drawn ploughs, seeders and planters – largely museum pieces in advanced economies.

“For now, outside investors haven’t cottoned on,” concludes Chataika. “Just look at the people”. He cites the appointment of Mthuli Ncube, Minister of Finance, in September 2018. Indeed, it’s hard to get more technocratic than a PhD in Mathematical Finance from Cambridge University. “It’s no longer Robert Mugabe. And personality matters in Africa.”

We had found some answers and I left Tendai to finish his work in Zimbabwe. While I hadn’t reached any firm conclusions, one thing seemed obvious. It was no longer Robert Mugabe. So, despite the details being only marginally clearer, the trajectory for Zimbabwe had to slope up.

Echoes from the past

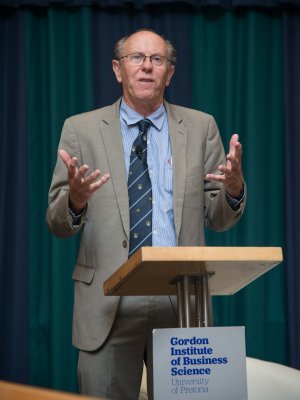

On January 13th this year the Zimbabwe government announced the tripling of fuel prices, sparking widespread protest and violence. Back at home in Johannesburg, I was back to conventional sources of information intel. That is, at least, I was until a forum on Zimbabwe at GIBS in late February. This time MDC Senator David Coltart was the source of my on-the-ground information scoop. A seasoned politician and human rights lawyer, he described the 2018 elections as “the most illegal election ever conducted in Zimbabwe”. He categorised the military’s reaction to fuel price protests as “a crime against humanity”. And he told us that just days before two colleagues of his were illegally abducted by the military in the eastern city of Mutare. Coltart closed to a soundless audience and a Highveld growling storm overhead. He outlined how in his speech following in the wake of the looting, President Emmerson Mnangagwa used language he hadn’t employed since the Gukurahundi massacres of Ndebele civilians in the early 1980s. On that occasion, then-President Mugabe sent his North Korean-trained 5th Brigade into Matabeleland and the Midlands to quell alleged dissent to Zanu-PF rule. Then-Minister of State Security, with control over the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), Mnangagwa continues to distance himself from the deaths of what the International Association of Genocide Scholars estimates to be some 20 000 people.