As an arts graduate with no formal corporate experience, Thando Mtsweni, who had just returned to South Africa after teaching English in China, wanted a course that would fast-track her career. She chose GIBS and, despite feeling imposter syndrome when she found herself “in a room full of extremely talented young graduates who are all eager to win in the world of business”, she describes the experience as life-changing.

“The culture was challenging, from having a name tent on your desk for lecturers to call you out to answer questions in class – which you can imagine would be an introvert's nightmare – to contributing in every syndicate assignment,” she says. “But the Postgraduate Diploma in Business Administration programme unlocked my potential and was perfect for my personal growth. Some opportunities to present would come five minutes beforehand, and I’d take them. My confidence increased in public speaking and networking, as well as my critical thinking and decision-making skills. I learned that nothing ever grows in your comfort zone.”

Mtsweni also chose GIBS to gain skills that would help her start a business. These have been valuable in her latest venture: manufacturing transparent face masks that organisations, deaf people, and deaf schools can use to improve communication.

“The deaf community already face many barriers and wearing masks has added a new one to their daily lives,” she says. “This is because they rely on non-manual parameters, such as lip reading, facial expressions, head tilting, and shoulder signals, which all add meaning to sign language.”

To test the idea, Mtsweni invested her own money to make 100 masks, with materials sourced from Oriental Plaza in Johannesburg and put together by two tailors in Maboneng.

“I started with an initial design of transparent masks, which were made of Polyvinylchloride (PVC) covering the mouth area and a bit of cloth on the upper and lower part of the mask,” she says. “The problem was the fogging, which created vapour on the mask. I had to do more research on materials that don’t fog up, and I found an anti-fog spray that’s used on the PVC material to keep it clear.”

Spreading smiles

So far, the project has received a lot of positive media attention. Unfortunately, sales have been slow, with the business selling 50 masks in the first month and the numbers falling ever since. The business also relies on hard-to-get fundraising because Mtsweni donates a lot of masks to deaf schools.

“Sales aren’t doing well,” she admits. “I’ve reduced the price and am working on a social media campaign to drive traffic to the website. But even though I’ve been in business for months, I haven’t started making a profit.”

She believes that part of the problem might be because selling only online is too limiting. Also, people could be resistant to wearing something different, like a transparent mask. This speaks to her concern that there may be a “misalignment of the target audience for which I intended to create value”.

“The mask is primarily for deaf people, or people working in deaf organisations, but I’ve had a lot of enquiries from the food industry and resellers,” she says. “In fact, for these masks to work, we all need to wear them so that deaf people can lip read when we’re trying to communicate with them.”

Mtsweni believes these masks have the potential to improve all our lives, not just by promoting equity and inclusion but by spreading much-needed smiles in a difficult time.

“The fact that the mask is transparent, trendy, and inclusive sets me apart from manufacturers who make cloth masks,” she says. “I’ve even had manufacturers contact me on social media to find out how to make the masks. The main challenge is finding the right materials as it is still a new market.”

Despite the challenges, Mtsweni is optimistic about her prospects and confident about her competitive advantage. As a first mover in the market, she has the opportunity to establish strong brand recognition and customer loyalty.

“I have the time to develop economies of scale and cost-efficient ways of producing and developing these masks before competitors enter the market, the same way I was able to find solutions to the fogging by establishing an anti-fog spray,” she says. “I’ll capitalise by continuously aiming to improve my strategy.”

Building an inclusive world

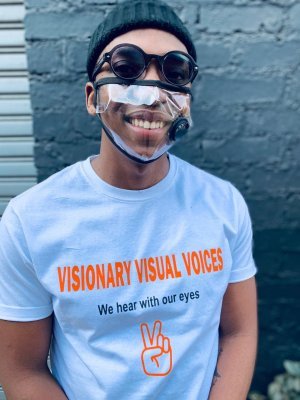

The face masks are the first project of Visionary Visual Voices (Pty) Ltd., a company Mtsweni started in 2019 after attending an international deaf festival in France.

“I was inspired to start a company that would help organisations create deaf-friendly experiences,” she says. “I also wanted to find deaf talent and showcase it in global events such as Deafnation in the USA and Clin d’Oeil 2021 Festival in Reims, France. These exhibitions give deaf people across the world an opportunity to showcase their unique culture through art, theatre, socials, music, and many deaf businesses selling their work annually.”

She plans to grow the company by doing consultancy work to contribute to social inclusion for deaf customers and deaf employees. Some solutions include providing basic sign language training so that all employees can communicate with the deaf. (She’s also in communication with GIBS to start an alumni sign language club for any graduates who want to learn; stay tuned for updates.)

“I’ve managed to educate so many people through radio and TV interviews and influence them to think differently about deaf issues,” she says. “Most people didn’t even know that deaf people rely on lip-reading to communicate and that masks had an impact on deaf people’s communication. But through the work that I’m doing, I’ve been able to influence people to think differently.”

Mtsweni has also challenged people to get out of their comfort zone and take the initiative to learn sign language. She even challenged her classmates to learn how to use sign language to greet the deaf CEO of an NGO they were investigating for an assignment. Not only did this make the CEO feel included, but it also showed group cohesion and an ability to “fully immerse ourselves in deaf culture while solving problems for the NGO”.

“Stuart Milk [a global LGBT+ human rights activist and political speaker] said that we are less when we don’t include everyone,” she says. “Therefore, it is our responsibility to work towards social inclusion and accessibility for all.”

Statistics

- The World Health Organisation estimates that 466 million people iworldwide have disabling hearing loss (6.1% of the world’s population).

- 432 million (93%) of these are adults (242 million males, 190 million females) and 34 million (7%) of these are children.

- Approximately one-third of people over the age of 65 are affected by disabling hearing loss while more than one billion young people (12-35 years) are at risk for hearing loss due to recreational exposure to loud sound.

- Unless action is taken, it’s likely that the number of people with disabling hearing loss could rise to 630 million by 2030 and over 900 million in 2050.

- The overall annual cost of unaddressed hearing loss globally is US$750 billion.

Source: WHO