If great ideas were born simply by putting a bunch of people into a room with pizza and a whiteboard, then everyone would be doing it. In reality, however, it’s not that simple. And it’s made more complicated by a growing aversion to thinking. Not out-of-the-box thinking, but plain, simple, no-frills applying-your-mind-to-a-problem thinking.

“There is an intolerance around deliberate processes or thinking about thinking,” says Vincent Hofmann, co-founder of employee experience design firm BetterWork. “You cannot get to a culture of ideation and innovation unless you are willing to go really slow and think deliberately.”

Hofmann, a part-time member of the GIBS faculty, adds: “This is not a South African phenomenon, but a global phenomenon that people aren’t willing to slow down and really think. People are caught up with ideating faster and solving things quicker. They are being told their competitors are coming for them and that a start-up will eat their lunch. All these cute statements make you believe you’re in a game that’s so quick.”

This absence of deliberate thinking hampers our creativity, our ability to generate ideas and to rationally reflect and identify the potentially good ideas from the bad ones.

The likes of Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, an advocate for conscious thinking in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, reinforces the value of a slow, deliberate and analytical approach rather than quick, reactive thinking. Kahneman’s work tells us that shortcuts don’t have a place in creative thinking, says Hofmann. But often, when companies get to the point of trying to drive innovation, they are relying on employees for whom creative deliberation has long been sidelined. This impacts the idea-generation pipeline and the quality of the ideas being spewed out.

There is an intolerance around deliberate processes or thinking about thinking.

Junk in, junk out

Recent research published in the De Economist journal by Bruce Weinberg from Ohio State University and David Galenson from the University of Chicago tells us that some innovators peak in their mid-20s and others in their mid-50s (based on a study of 31 Nobel prize-winning economists). However, based on a 1968 longitudinal research study by George Land and Beth Jarman, most of us lose around 96% of our creativity between the ages of five and adulthood, says Gill Cross, head of learning innovation at GIBS.

“Being innovative has largely been beaten out of us [by the time we are in our mid to late-20s] and when we get into corporates, well, they are not designed for innovation but for continuous business improvement. But efficiencies and continually improving business are not the same as innovation,” says Cross.

Right now, it is in vogue to ponder ways to improve innovative output or, as a December 2019 Stanford Business article by Dylan Walsh sought to explore, how to evaluate the potential of an idea. But the reality is that without empowered employees encouraged to think, and given room to create and fail, there will be no pipeline of decent ideas to ponder.

“If we really wanted to change the way people think and segue into innovation, this is a 20-year process which starts by changing our schooling system,” says Cross. “It’s about teaching curiosity, sense-making, maybe with some process-driven problem-solving stuff, and collaboration. All those good things.”

Until that happens, Hofmann warns of the snake oil salesmen punting four or five-step processes and preaching the predictability of the ideation process. “That is never the case,” he says. “To be honest, all innovation is ambiguous, and all innovation is going to be uncertain and is unpredictable.”

All a company can do is seek to build the right muscles to make good decisions that support quality ideation, and not a five-step cutout process that fiddles around the edges.

Building muscles

Effective innovation is, in this respect, exactly like a CrossFit session. You don’t start out knowing how to do double-unders or pull-ups. Rather, you first build the requisite muscles to enable you to complete the more complex actions. In the context of corporate ideation, this means building effective teams and – as scary as this may be for some companies – empowering people to think.

...efficiencies and continually improving business are not the same as innovation...

“Amy Edmondson [professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School] talks about the antecedent to innovation being the healthy team,” explains Hofmann, “so before you get innovation you need a healthy team.”

This is BetterWork’s starting point: uniting people and helping them to come together in a functional way. “Yes, they might have different motivations, but they need to agree they are working on the same stuff. Sometimes they need the actual process of learning, because that habit has gone away because school has beaten that out of them,” says Hofmann.

Applying the work of Dave Snowden [founder of Cognitive Edge], BetterWork comes into an organisation and shakes things up by probing the current system and, as Hofmann puts it, “Burning the veldt to see the rats”. Only once dysfunction has been identified within the company can a healthier system, which supports people, be fostered.

Once you’ve generated ideas – loads of them – how do you know if they’re any good?

People and passion

Figuring out what is holding people back from producing the best work of their lives is a passion for Hofmann, who draws on the work of giants like renowned management consultant Peter Drucker and Russell Ackoff, a founding member of the systems thinking movement.

In South Africa, trust represents a significant blockage to innovation. “The people coming to us in our non-profit organisation, The GoodWork Society, are having the sorts of conversations they should be having out loud at work. Many of these stories would naturally diminish any reason to share good ideas,” says Hofmann. “The last session we ran was on sexual violence and about 50 women came to the session and almost everyone said they would not give discretionary input to their company if they didn’t even feel the company had their backs.”

Companies facing trust issues of this magnitude, where employees are disinclined to even invest their brain power, have bigger fish to fry than picking the best idea on the table. They must get back to the basics of building the high levels of psychological trust and freedom employees need to innovate, says Cross.

Creating the conditions for innovation

For many companies, however, designing the conditions for innovation will not require a complete culture overhaul, just a few simple tweaks. “For example, try counting how many times the word ‘customer’ comes up in your next five exco meetings,” says Cross. “Or, on a personal level, try simple things like dressing differently, taking down the walls in your office, putting your lipstick on with the other hand, driving a different route to work, sitting together and then just see what happens naturally. Something will change.”

A personal favourite, she adds, is taking a map and putting your finger on a country you’ve never visited, then listening to the music of that country. “These are small micro-tweaks one can do to try develop a relationship with cognitive flexibility,” explains Cross. And it is this mental flexibility that opens the door to new ideas and new ways of thinking.

Once you’ve applied the tweaks then go in search of other people – both inside your organisation and beyond – who have “cool networks and relationships, then the flow of energy and information becomes unblocked,” says Hofmann.

While happy teams and skilled people who are meeting and sharing frequently are the fuel for the ideation fire, beware the allure of ideating in corporate siloes.

“Ideo, for instance, the world’s largest design firm, speaks about five ways to brainstorm. You rattle them off, and you tell a team to do it and they go off and produce ideas that will never see the light of day,” says Hofmann. This happens because people are producing ideas in a vacuum, in the absence of talking to their customers. “Sure, they’ve done brainstorming and ideation perfectly, and they’ve successfully ticked off all the best practices, and yet nothing materialises.”

This tells us that the journey of ideation is just half the battle. Once you’ve generated ideas – loads of them – how do you know if they’re any good, and what do you do with them?

Spotting a winning idea

This is a tricky one, as history is filled with examples of great ideas that went unappreciated and unnoticed in their time, only to be dusted off in the future.

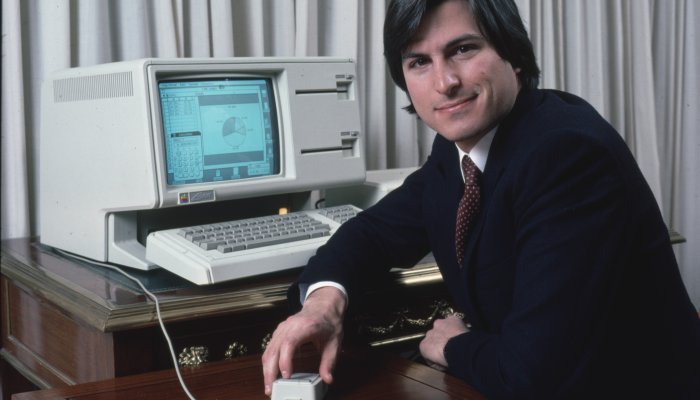

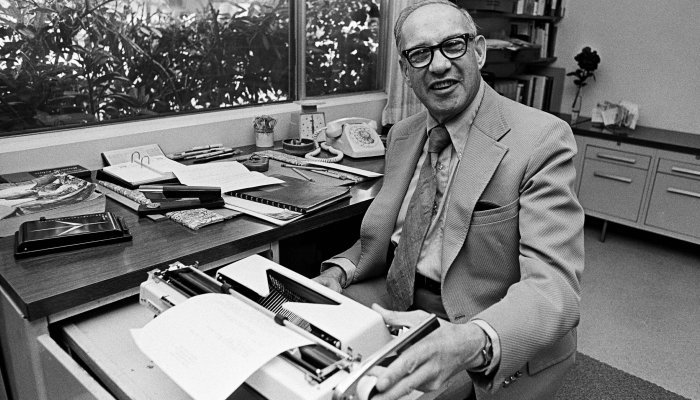

Consider Steve Jobs and the computer mouse. Patented by Douglas Engelbart of the Stanford Research Institute in 1967, Jobs spotted the potential for the device and introduced it to Apple users in the 1980s. “We have these anecdotal stories, these pieces of evidence where a perfect design process resulted in a thing that no one saw value in, and then someone else came around who was a good curator and said: ‘I’ll have that’,” says Hofmann. “Of course, the computer mouse story is told very differently depending on who tells it: that Steve Jobs had some sort of epiphany or saw the mouse in a dream!” But the reality is that, sometimes, spotting potential is just a lucky break.

This, reiterates Hofmann, is because great ideas are not born with the flick of a switch. You only need to look at one of Da Vinci’s many notebooks to appreciate that great ideas are messy and often muddled. Some stick and some don’t; some get built and some fall apart. But if you don’t give them wings, you’ll never know.

Where to start

· Sweat the small stuff – Instead of grand interventions, why not run ‘safe-to-fail’ experiments or probes, not to find something but to see something happen, recommends Vincent Hofmann of BetterWork. “These come up with the most amazing ideas.”

· Tune into the outside world – GIBS head of innovation, Gill Cross, uses the example of American multinational 3M, which has effectively created a semi-permeable membrane between the business and the outside world. “Their slogan, ‘Collaborate early and often’, is embedded throughout the organisation,” she says, noting that the approach is geared towards interaction and adaption to the needs of the outside world.

· Make innovation mainstream – Sparking creative thinking starts by sharing, by building bridges and by amplifying all voices within a company so everyone is invited to think and share ideas. But, says Cross, “Often, existing structures in companies just suffocate innovation.”

· Build trust with all employees – All employees should be regarded as a potential source of inspiration, which means everyone needs to be engaged. “Often the problem – beyond maybe low levels of trust and not wanting to share – is that withholding your mind is the only power an employee has,” says Cross.

· Don’t put innovation on a pedestal – The Innovation Ambition Matrix, which is a refinement of H. Igor Ansoff’s classic mathematical diagramme, says companies should be spending 70% of their time on core roles and improvements, 20% on adjacent activities that expand slightly to new types of streams, and 10% on the truly transformational. “I think we’re seduced by innovation,” says Cross. “As a result, people are jumping too quickly and actually losing the engine of their business.”