Strategies by group size

Prof Marwan Sinaceur, professor at ESSEC Business School in Paris, says that interactions can be classified in many ways, but arguably the most helpful when it comes to influencing people is by size.

He breaks strategies for influencing into three size-based types: one-on-one situations (interpersonal negotiation); small groups (influence); and large collectives of people (change management).

“The way you deal with each of these situations will be different,” he says. “The nature of the interaction, which can be determined by size and complexity, dictates your strategy. Usually, you have people looking at this from the micro side (psychologists who seek to understand interpersonal influence and groups) and experts from the macro side (sociologists who focus on large collectives). I try to look at this subject from a manager perspective where the disciplinary background is not important – what’s important is being able to tackle these different situations.”

One-on-one negotiation

In one-on-one situations, Sinaceur says, you have the most control and the highest chance of influencing the person with whom you are dealing, as interpersonal negotiation is very interactive. The situations tend to focus on relationship or conflict issues and listening to the other person to understand their concerns and interests is key. “The challenge is often not to understand what behaviours work best, but how to actually adopt those behaviours in any given concrete situation,” he says. “For example, if you are dealing with an unhappy client, colleague, or stakeholder, you know it’s important to listen. However, understanding that doesn’t always mean we do it well.”

He suggests that the best way to improve your interpersonal negotiation is to practise and master effective behaviours, such as active listening and asking questions to understand other parties’ underlying interests. It is also helpful to look beyond verbal behaviours as nonverbal behaviours are another means to efficiently influence others.

Influence in small groups

In a group or team situation, leaders are seeking to move a group of people in a particular direction towards a goal. Sinaceur says the most important aspect here is for leaders to understand the social dynamics at play within the group, which adds a level of complexity to the strategy for influence.

“The questions you need to ask are things like, ‘Who has the power? What are the sources of power? Do you have the majority with you, or are most of the people in the group against you? How will social pressure play out in this group? What will influence this group to move in your direction?’ Once you have thought about these things, you can examine the specifics of your strategies to influence the group.”

For example, he says, you might consider how best to organise the group so that discussion is not dominated by certain people, how to structure the format of a meeting to focus on the key issues (rather than getting bogged down in details), or how to run the meeting most effectively when you do not hold the social power. Every group needs different strategies, depending on the specific power dynamics.

“In a meeting, you might have experts and stakeholders who seem reserved, but who could have a big influence on your project,” says Sinaceur. “It’s important to understand that the extent to which people speak up doesn’t necessarily represent real power.”

To avoid discussions being dominated by certain stakeholders who have a particular agenda, you might make a rule that the group will map out all the issues and possible scenarios before you start speaking about possible solutions. “Discussing processes and ways of working first is particularly effective across many group situations,” says Sinaceur.

Influencing large-scale change

According to Sinaceur, effecting influence in large collectives is the most complex situation as you have the least control and interaction with the people whose behaviour you are trying to change. This type of influence often boils down to change management, and Sinaceur says the first step is a thorough understanding of both any psychological and any organisational barriers to change.

He says the Covid-19 vaccination campaigns are a recent example of where governments were trying to influence people to take specific actions (namely, to get vaccinated). To develop a strategy to influence vaccination uptake, they needed to start with understanding vaccine hesitancy. “If you want to overcome vaccine hesitancy, you need to understand what is at the root of it. Is it a case of people not believing the messages that vaccine campaigns are seeking to deliver, or is the problem related to a lack of access to that messaging, or a lack of means to implement the action?” he says. “We’ve seen that studies show that making it easier to adopt the behaviour can have a dramatic effect on vaccination rates. There is a multiplicity of factors that need to be taken into account.”

He says that one important challenge that needs to be acknowledged when it comes to influencing large collectives is that there’s usually not one way of doing so. Global warming is a case in point. Many organisations around the world agree that behaviour change is necessary, but they may not all have the same strategy or messaging in mind to facilitate change. One might focus on encouraging people to take up personal responsibility; another on corporations’ carbon emissions.

“You also need to consider the timing of your change management programme,” he says. “Are you going to roll out your strategy over a long period, or all at once? This will depend on what you are trying to achieve and whether you are targeting incremental change or revolution.” For example, you might put in place several measures to encourage behavioural change (a step-by-step approach) or, alternatively, implement a new policy to effect immediate change (an all-at-once approach).

He says other strategies for effective change include how to approach categories of people within the larger group, for example people who will resist your change management programme; how to strategically tap into any allies you have available to you; and using pilot testing and proof-of-concept data to effectively develop your implementation strategy.

The role of neuroscience in persuasion

Ian Rheeder, who is a part-time member of the faculty at GIBS and a chartered marketer (SA), says that understanding a few key basic neuroscience concepts can also assist leaders as they seek to negotiate, lead and influence.

“Dr David Rock's 2008 neuroscience model called Scarf (status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness) explains the five basic needs of human beings,” Rheeder says. “For managers and leaders, understanding this can help to influence and inspire people to change. It illuminates why, when we persuade, we need to make the other party feel like they are important, help them understand exactly what the offer is, give them an option B, and make them feel they are liked and are being treated fairly.”

He says leadership is about inspiring people to move towards a goal through a top-down approach of giving them hope, energy and “a why”, while management is about influencing people to do things through a bottom-up approach.

Box:

Scarf in action

Rheeder says implementing Scarf into your persuasion tactics will help you to get people to buy into your strategy. For example:

- Status:

Engage with people respectfully. Take the time to understand their culture and subjective situation. Ask “What’s important to you about…?” - Certainty:

People today are overwhelmed by decision fatigue. They are more likely to be persuaded by leaders who can articulate challenges and solutions with clarity and certainty. - Autonomy:

People want options and the room to choose between those for themselves. - Relatedness:

Everyone wants to be liked. Gallup studies show that people are more likely to be engaged at work if they have a friend within the organisation, and that a manager or team leader alone accounts for 70% of the variance in team engagement. Working on interpersonal skills can help you improve your ability to influence people. - Fairness:

Humans are hard-wired to want fairness. Striving for win-win situations and ensuring people are treated equally goes a long way in generating support.

<BOX ENDS>

Persuasion levers

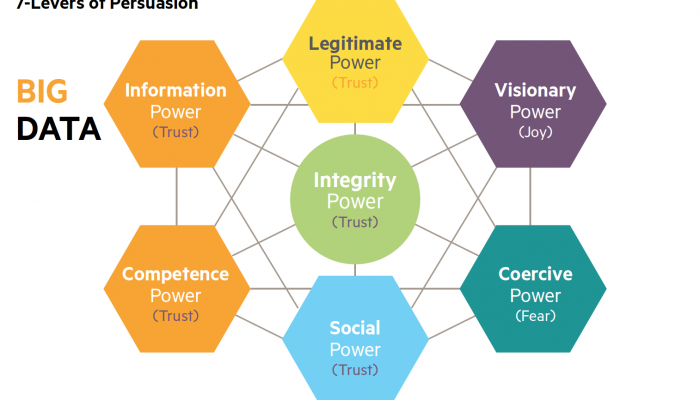

Rheeder says managers and leaders are able to draw on seven levers of power to influence people by tapping into their primary motivations. Most of these relate to trust, which is essential.

Persuasion is also possible through visionary power (joy motivation) and coercive power (fear motivation), but Rheeder cautions that overusing fear results in a person’s rational "human" brain shutting down cognitive and creative reasoning of the prefrontal cortex and reverting to the ancient mammalian brain (limbic system), which operates on “fight or flight” mode.

[insert 7 levers graphic here]

Trust is at the centre of any successful persuasion strategy. Trust also underpins integrity power (“Can I trust this person to do what they say they will do?”); social power (the clout needed to lead); information power (having the right information to lead); legitimacy power (valid leadership status); and competency power (the capability to lead).

Rheeder says the most effective leaders will use a mix of these levers. Ignoring any single lever completely will damage persuasive power in the long run.

Practical pointers

“Modern neuroscience shows us people are strongly motivated by the emotional engagement of trustworthy relationships,” says Rheeder. “Building on from that, there are some golden nuggets we can use to persuade people and get their cooperation in a high-trust way, without forcing compliance.”

These include:

- Asking good questions:

Rheeder suggests following Dale Carnegie’s 1936 advice: “Ask questions the other person will enjoy answering.” Ask questions that build rapport, trust and confidence. Think carefully about your question sequence to help people to think deeply about what they really want. - Tapping into humans’ social nature:

“Multiple studies show that, in sales, customers single out the calibre of the salesperson as being 200% to 400% more important than the products they sell,” says Rheeder. “What this tell us is relevant small talk (and asking questions) is critical at the start of negotiations. People are most likely to follow you if they relate to you, so find similarities (i.e., shared values) and give genuine praise.” - Promoting trust:

“One of the best ways to influence is to build trust by showing empathy,” says Rheeder. “And one of the fastest ways to build trust is to be the first to do a small favour (servant leadership). Remember that even a tiny loss of trust – through perceived unfairness or dishonesty – can cause a disproportional loss of influence.”

Pull quotes:

In one-on-one situations … you have the most control.

People are strongly motivated by the emotional engagement of trustworthy relationships.