The global wealth gap between the rich and the poor has never been as immense as in 2021, with the recent pandemic proving to be good news for the super-rich.The old adage stating that money begets money still holds, with the ‘global millionaires’ club’ expanding by a staggering five million individuals from 2019 to 2020.

Let’s put that into perspective: the current tally of millionaires worldwide now stands at 56 million, according to www.statista.com. Moreover, massive gains were seen in established first-world economies such as the US (1.73 million) and Germany (633,000), while emerging nations – think Brazil, India and Africa – experienced a decrease in numbers.

This collective surge in private fortunes boomed despite Covid-19’s devastating economic impact and the corresponding rise in unemployment, skewing the wealth gap even further. It is a sobering thought, with a Credit Suisse report showing 1.1% of humans effectively own 45.8% of global household wealth.

One of the major reasons for this inequality is the lack of healthy competition in business. Big monopolies have played havoc with capitalism’s regular supply and demand equilibrium, causing crucial imbalances in key market segments.

This poses a colossal problem as it means that three billion people – more than 50% of the total human population – are effectively powerless against the large monopolies when it comes to affecting market forces. An even bigger issue looms, though: there seems to be no economic model to replace capitalism effectively.

Winston Churchill said it best when he addressed the British House of Commons on the pitfalls of democracy and noted that “capitalism is the worst economic system, except for all the others”. A few decades ago, one could have argued that there might have been a place for communism or socialism, but the collapse of the Soviet Union saw the free-market economy burgeon where Marxism once ruled the roost.

The original definition of capitalism as ‘an economic-led system based on private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit’ can’t work if said producers lose control over their ability to maintain a healthy profit margin. This bears an argument for some social democracy compromise, controlled through taxation, competition laws and market regulation.

This is exactly where the concept of fair trade comes to the fore. The first mention of the term dates back to the late 1940s in the US and early 1950s in the UK, when OXFAM began promoting and selling crafts by Chinese immigrants in their shops. NGOs across Europe followed suit, and by 1964, a Fairtrade organisation had been formed in the UK.

The Fairtrade label grew from strength to strength, with 'world shops' or 'Fairtrade shops' soon opening around the globe. These served as retail outlets and as a network championing the idea of fair business ethics. Today, the yin-and-yang leaves of the Fairtrade icon has arguably become the most powerful and globally recognised of all ethical labels.

The main aim of the Fairtrade logo is to signify to consumers they are investing in a brand with the necessary feel-good credentials in place, backed by rigorously audited international standards. These evaluations apply to more than just ethical trading practices and enforce the producers to institute acceptable environmental and labour policies, too.

In real-world terms, this translates into employers ensuring acceptable living conditions and fair wages for their workers, using environmentally-friendly fertilisers and organic chemicals, eliminating all forms of discrimination, and most importantly, sharing a part of the company profits with their workforce as a ‘Fairtrade Development Premium’.

In return, the said corporation is then permitted to brand its relevant product range with the Fairtrade logo. The trust and ethical gravitas associated with the icon often elevates the specific brand in the eyes of their consumer market.

A range of interconnected benefits goes hand-in-hand with the Fairtrade connection, allowing the company to potentially institute premium pricing practices. This generally converts into a win-win situation for both employer and labour force, as all parties benefit from an increased share in the company’s profits.

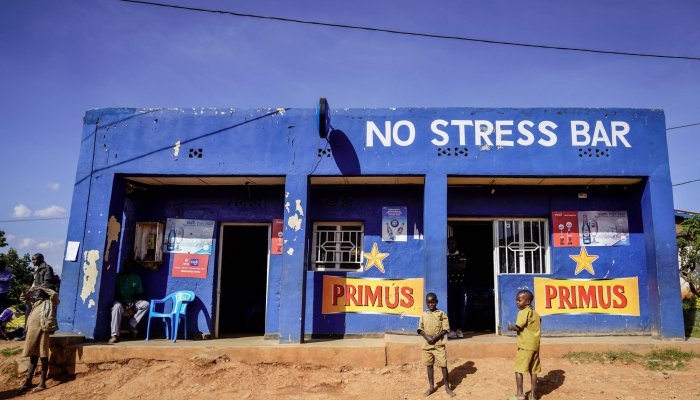

Fairtrade has proven to be a gamechanger in business in Africa, mainly because of the robust agricultural sector driving rural economies in many countries on the mother continent. It goes without saying that most players are small-scale farmers or informal cooperatives, with many of them dependent upon the protection that Fairtrade certification guarantees.

A staggering 96% of global Fairtrade products come from the agricultural sector and often fall within the areas of raw, unrefined produce. Coffee, cocoa, table grapes, soft fruit, raisins and cotton are just a few of the farming industry sectors supported by the global Fairtrade movement.

One South African company that bought into this ‘fairness revolution’ during its earliest stages is the Bean There coffee company. “We absolutely believe in equality and sustainability in the agricultural sector, especially when it concerns ethical trading,” explains Jonathan Robinson, founder and CEO of Bean There.

“Even though most of our business dealings are with cooperatives and small-scale farmers in Africa’s distant Rift Valley, their quality of life is intrinsically linked to the produce we purchase from them. Happy suppliers mean less stressful business dealings, and Fairtrade principles allow us to invest in improving living and labour conditions while simultaneously promoting eco-friendly farming.”

Bean There R&D manager, Cuth Bland, agrees wholeheartedly. “The countries along the East African Rift Valley produce some of the best coffees in the world (one could arguably say the finest). High altitude, rich volcanic soil and access to the extensive lake networks ensure perfect cultivation conditions for the Arabica coffee varietals first discovered and harvested wild in the Ethiopian Highlands.”

Although some coffee still grows wild here, most cherries (raw coffee fruit) in East Africa produced for Bean There are cultivated by small-scale farmers before being processed at local washing stations. Rough terrain often forces farmers to transport their sacks of coffee cherries to the closest washing station by bicycle, donkey or on foot.

These washing stations are easy to spot because of the characteristic raised drying beds that run in terraced rows down the hillside, and the harvest from a single catchment area could reach hundreds of metric tonnes. Traditionally, the coffee is fully washed, and this process is well-organised and understood, but farmers are often at the mercy of unscrupulous buyers.

However, carefully produced, naturally processed coffees are becoming more sought after and can net farmers a significantly higher price. They must weigh up the risk of losing an entire harvest of cherries due to careless sorting, bad weather or other unforeseen problems. As a result, it means quality, naturally processed coffees remain a rarity.

The guarantee of a fair price and logistical support through the Fairtrade network enables farmers to pool their resources and focus on growing the best beans possible. And when all these conditions come together, their typically sweet and intensely fruity coffees – often with crisp, clean acidity – prove that the best coffee in the world can be grown under an African sky.

“From a Bean There perspective, the Fairtrade system assists in training and supporting a host of small-scale producers, and we benefit enormously because of the consistency in quality and business practices this engenders from country to country,” Robinson continues.

In the end, the consumer is the real winner. A quality product allows them to revel in a range of products, encompassing everything from Ethiopian coffees’ floral, citrus notes, the complex blackberry aromas in Kenyan blends, or the elegant, balanced flavours of Rwandan coffee.

Fairtrade benefits for South African brands

- Networking.

Joining the global Fairtrade Africa community creates a range of networking opportunities through their worldwide events as well as their wide-reaching social media platforms. Follow them on @FairTradeAfrica or visit their website at www.fairtradeafrica.net.

- Part of the profit from Fairtrade purchases is reinvested in healthcare, education and community development projects.

Farmers in Breede River Valley have benefitted from a beautiful pre-school, a women’s empowerment project, and assistance in completing tertiary education degrees.

- Keep it local.

The Fairtrade concept makes African society more equal. In fact, the entire continent benefits from small-scale rooibos tea growers in Wupperthal to farmworkers in Stellenbosch and coffee farmers in Moshi, Tanzania.

- Maintains South Africa's position as a Fairtrade emerging economy.

South Africa is a trailblazer and can prove to the world’s superpowers that we can become a worthy economic partner.

- An excuse to drink more wine.

South Africa is the #1 producer of Fairtrade wine globally, so help us all win (and give wineland farmers a reason to adopt the Fairtrade model).

- Fair trade is one of the Top 10 most desirable brands on the planet.

Yup, just a few places down from Apple! Millions of consumers across the globe, from the UK, Germany and Brazil to India, choose Fair Trade products every day. Join this international movement in support of the people who grow our food.

- Support sustainable agricultural practices in South Africa and around the world.

This is seriously one of the easiest ways to contribute to saving the planet. The next time you shop, make sure you look out for the FAIRTRADE Logo; the seemingly insignificant act of your purchase will in fact bring about extraordinary change.

Fairtrade facts and figures

Fairtrade facts and figures

- 1.5 million workers are linked to the Fairtrade network in 74 countries.

- A range of over 30,000 Fairtrade products is sold in 150 countries globally.

- 64% of Fairtrade farmers are from Africa and the Middle East.

- Six of the top 10 Fairtrade countries are from Africa (South Africa is not one).

- Fairtrade SA was launched in 2010, and sales have grown to R287 million.

- There are 113 certified Fairtrade farms in South Africa (20 of them are wine farms).

Source: Brand South Africa – 2015

SOURCES:

www.wfto.com – World Fair Trade Organisation

www.fairtrade.org.za – South African Fair Trade Organisation

www.brandsouthafrica.com – Brand South Africa

www.beanthere.co.za – Bean There Coffee