On paper, the world of retail has been turned on its head in recent years as technology has enabled a better, more streamlined customer experience. The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) tools such as chatbots and QR codes, new devices like barcode scanners and portable point-of-sale devices that make it easier to pay, and the delivery services that proliferated during Covid-19 have altered the way we shop.

In practice, however, if you do venture out to your local shopping centre or convenience store, it probably looks, feels and acts much as it always did.

Or does it?

Digital: The star of the show

Boutique luxury stores, mega malls, local spaza shops and online platforms have all been impacted by one game-changer over the past decade: digital technologies. Both physical and virtual retailers now use and rely on digital technologies to deliver an efficient consumer experience.

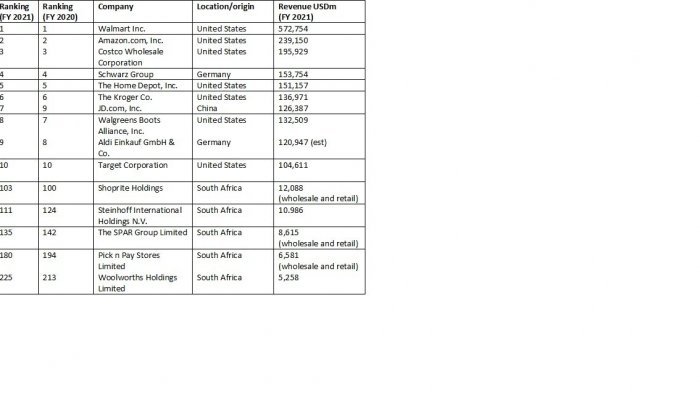

In Africa, global consulting firm BCG notes that “digital marketplaces for inventory, e-payment services and other tech solutions are transforming traditional retail”. Globally, digital retailers received a boost from Covid-19, which drove people online to such an extent that “the majority of the top-10 retailers have actively boosted their digital capabilities through either the implementation of in-store technologies or through enhancing their omnichannel offerings”, says the 2023 Deloitte Global Powers of Retailing report, which ranks the 250 leading retailers by revenue.

Top-ranked Walmart (see Figure 1) saw e-commerce sales grow “by 12.8% in FY2021, following 63.5% growth in the previous year”, according to Deloitte. While noting a return to physical stores since Covid-19, Walmart remains committed to its digital growth while also investing in improving the in-store experience. This omnichannel approach is also finding favour with other leading global retailers, like Schwarz Group, JD.com and South Africa’s Pick n Pay.

Omnichannel retail is not a new concept. It dates back to the early 2000s and talks to a strategy that creates a seamless customer experience across a brand’s physical and digital channels. Omnichannel has been one of the most impactful shifts in retail thinking in recent years, one that seeks to break down siloes and put the consumer at the centre of the shopping experience.

It’s not the only change worth noting.

Where we’ve come from…

The 2008 global recession had ripple effects across the retail landscape, forcing the closure of companies and putting consumers under pressure – much like they are at the moment amid a worldwide cost-of-living squeeze compounded by high inflation and rising rates.

What stands out when you compare 2009 with today’s landscape, according to CNBC’s Courtney Reagan, is the rise of direct-to-consumer, with manufacturers and wholesalers taking advantage of e-commerce channels to sell to the consumer directly, without using middlemen.

The normalisation of online buying has also delivered a shock to bricks-and-mortar stores, which have met the challenge with a range of responses such as harnessing data to create personalised marketing and discount strategies; attracting eco-minded consumers by reducing packaging waste; bringing branded stores and fulfilment centres closer to communities; and using influencers to reinforce the in-store experience.

Speaking during a Lagos Business School discussion on the impact of data on African retail, Angela Ambitho, from Infotrak Research & Consulting in Kenya, noted that attracting consumers to physical stores would require a careful eye on cost and competitiveness since it was increasingly more affordable to shop online. As a result, physical retailers “will have to think about how they use their retail stores, so they don’t lose out when especially the younger consumer decides there is no point going to a retail environment because they can do everything online.”

Chidi Okoro, a Nigerian executive business consultant, said that offering a one-stop shop experience would also appeal to African consumers, who want the convenience of getting everything they need from a single store. But, of course, they also want delivery options and online buying. In other words, the omnichannel approach.

Based on his experience, Pick n Pay’s omnichannel executive Vincent Viviers told Deloitte that “bricks-and-mortar stores will adapt going forward, but they will always remain important, and are actually a cornerstone of our e-commerce and delivery success”. He expects stores to become more experiential, filling the important need for a place where consumers can “see and experience products” and then acting as a base from which to deliver goods.

Ultimately, of course, the power lies with the consumer.

Shifting customer needs and wants

Market research firm Euromonitor International has identified 10 different consumer groups that emerged post Covid-19, including "back-up planners" (who were pushed to seek out new sources for products and services due to supply-chain issues), "climate changers", "digital seniors", "pursuit of preloved" and "the metaverse movement" (which embraces 3D digital ecosystems to support buying choices). Each of these groups requires a personalised engagement strategy on the part of retailers. For instance, the commitment from China’s Alibaba to achieving carbon neutrality by 2030, plus its support for using recycled materials and beauty products free of harmful ingredients, clearly aligns the retailer’s values with that of the "climate changers".

Fortunately, today’s retailers have a wealth of data on consumer preferences, drawn from loyalty card-linked promotions, marketing engagements and tracking online buying patterns. The more a retailer can know about its customers, the better. Which is why retailers – and companies in general – are increasingly keen to streamline multiple digital touchpoints under one banner: theirs.

Christele Chokossa, a Euromonitor International consultant, noted that retailers have picked up how consumers are being inundated by a barrage of online services and apps. She explains, “In 2022, 57% of consumers indicated they had to delete some apps to streamline their usage.” What is emerging, she explains, is the rise of the super app, with the likes of Amazon, WeChat and Uber, as well as South Africa’s Discovery Bank, leading the way. A treasure trove of important insights, if brands can consistently make their platform relevant to consumers – which means paying attention to new channels for engagement.

VR: Knocking on the door of the omnichannel

An emerging trend that has huge potential for retailers paying attention to consumer behaviour is virtual reality (VR).

In 2021, retail giant Walmart acquired an Israeli start-up called Zeekit. Last year, Walmart rolled out a "choose my model" tech feature which helps consumers make buying decisions by showing them how garments look on models with similar measurements. The next phase of the rollout should allow users to upload their own photos to virtually try on items – a step closer to buying via your personal avatar in the next iteration of the internet, the metaverse.

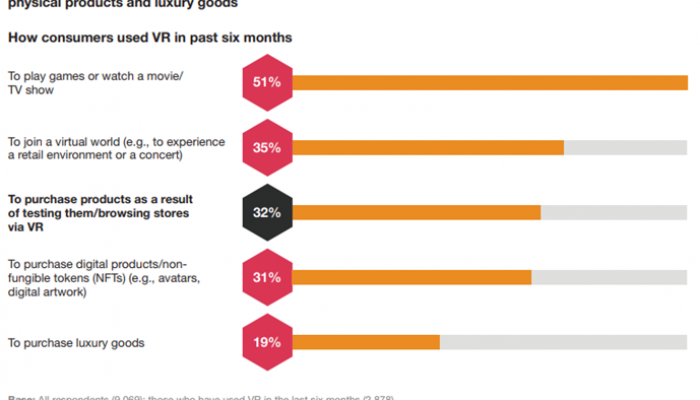

Once comfortable in the VR world, consumers are quite at home when buying through this avenue. PwC’s Global Consumer Insights Pulse Survey noted that of those using VR for entertainment, 32% had bought products after browsing stores via VR and 19% bought luxury goods through VR. A hefty 81% of respondents had “shopped across at least three or four channels over the past six months”, indicating that VR and the metaverse were emerging channels which retailers may need to consider “as part of their omnichannel presence”.

Re-purposing ‘old’ technologies for new markets

While VR is a new and exciting channel, existing technologies are also flexing their muscles after a digital makeover. The vending machine industry, for instance, is benefitting from new digital tools such as smart security, remote assistance and maintenance, and the Internet of Things (IoT). Just recently, Penguin Books in the UK installed a book vending machine at a railway station in Exeter, to feed the British commuter’s appetite for books on the go.

Vending machines may seem like the low-tech cousin to futuristic, fully automated and self-service shopping stores already doing brisk business in Hong Kong (Okashi Land), Japan (Lawson) and the US (Amazon Go). However, the Japanese have long been keen users of automatic vending machines, for everything from books to drones, clothes, dumplings, hot pizza and even engagement rings.

For a variety of reasons – including fewer machines selling alcohol and tobacco and the move to "tap and go" payments rather than the cash options that Japanese prefer – the number of vending machines in Japan is on the decline, from a peak of some 5.6 million in 2000 to four million at end-December 2021, according to the Yano Research Institute. In other markets, such as Germany, the smart vending sector is growing at pace and was expected to see compound annual growth of 8% between 2017 and 2021. High growth is also being seen in Latin America and Asia Pacific, so much so that market research company Technavio predicts the market will grow by almost US$10 billion before 2024.

Consolidation and partnerships

An African retail business trend, which was highlighted during the Lagos Business School webinar, is the growing dominance of franchise and affiliate models, and opportunities on offer for synergistic partnerships.

According to Thobeka Magubane, retail analyst at Trade Intelligence, “40% of traditional retailers in Morocco and Kenya are interested in affiliation or franchise models; and around 50% of Egyptian and 60% of South African retailers are also interested”.

What’s out of favour is big multinational retailers moving into African markets, said Professor Uchenna Uzo, faculty director at Lagos Business School. “In the past 10 years multinationals have been leaving African markets – largely South African brands – and local giants are growing.”

This will be a physical retail trend to monitor with interest amid the array of digital technology shifts and the continued rise of the metaverse.

Retail returns: Solving the e-commerce conundrum

When you think about the future of retail, do you think of robo assistants, human-less interfaces and artificial intelligence? Or do you think of a returns officer? More than likely it’s the former, but right now e-commerce retailers are battling to manage a burgeoning problem: merchandise returns. This is why the rise of the retail returns officer might be one shift that comes to bear.

The rise of returns

The rise in merchandise returns can be linked to the growing popularity of e-commerce and online buying, as well as the impact of Covid-19. From expected returns of 8.7% in 2008 and 7.3% in 2007, the National Retail Federation (NRF) in the US says retailers expected 16.6% of total retail sales would be returned by consumers in 2021. That’s about $761 billion in value. The NRF projected this would rise to $816 billion in 2022 (a steady 16.5%).

Returns come at a heavy cost to retailers. As the NRF explains, “For every $1 billion in sales, the average retailer incurs $165 million in merchandise returns.”

In the UK, online retail returns grew to 35% of total sales in 2022, despite an 11.5% drop in online buying, according to figures from ReBound, a platform that helps companies manage their returns. In an interview with the Internet Retailing website, ReBound MD Jelle Schoenmaker said, “With returns volumes increasing, the importance of ensuring a positive experience for each consumer is more critical than ever. Consumers want and need refunds quickly and are making decisions faster on what they want to keep, so brands and retailers need to ensure they are monitoring why products are being returned to improve their product listings.”

Given the economic costs, Schoenmaker warns retailers to “act now, tracking returns data to understand how carbon emissions can be cut from inefficient routes and how to provide shoppers with purchases they’re more likely to keep”.

Given these multiple touchpoints, one suggestion is to appoint a chief returns officer (or at the very least to add this portfolio to the responsibilities of another C-suite executive, such as the chief operating officer or chief financial officer).

What is a returns officer?

The role of a returns officer would span the entirety of the returns process, including monitoring customer satisfaction and the cost of the returns process. The idea was first touted by Alan Maling and Thomas Goldsby of the University of Tennessee in The Wall Street Journal. They envisaged an executive role that held responsibility for the “end-to-end returns process”.

Despite lip-service from the likes of global retailer Doodle’s chief revenue officer Dan Nevin, few retailers have (as yet) created a position dedicated to the returns process. Instead, many appear to be banking on artificial intelligence return technologies offered by the likes of Newmine, Optoro and Appriss Retail to fill the gap.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Over the past decade, the digitalisation of retail has introduced innovations such as chatbots, barcode scanners and QR codes, as well as portable point-of-sale devices.

- Since the Covid-19 pandemic online buying has accelerated, and delivery services have become a standard service.

- Research from Deloitte shows that the 250 leading global retailers are actively boosting “their digital capabilities through either the implementation of in-store technologies or through enhancing their omnichannel offerings”.

- Channels like virtual reality and the metaverse have potential to join the ranks of the omnichannel, while old technologies – such as vending machines – are benefitting from a digital makeover.

- In Africa, digital tech solutions are having a transformative impact on the ecosystem.

32% had bought products after browsing stores via VR