Chips: The bare bones

- When discussing the rate of technological advancement, most people quote Moore’s Law, which expects the speed of computer processing power and computer chip performance to double every few years.

- The transistors contained in computer chips jumped from around 2,000 to 3,000 transistors (basically fancy current and volt switches) per chip in the 1970s to billions of transistors per chip today.

- Without programmers to teach computer chips a logical language, these computer brains cannot complete the thousands of amazing tasks we ask of technology each day.

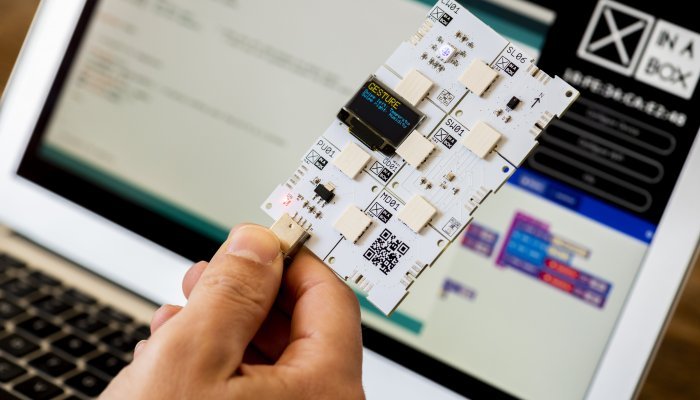

- XinaBox, a South Africa-born modularised electronics manufacturer and advocate for scientific education, is producing easy-to-use products that enable experiments and applications to be fast-tracked.

Computer chips are the building blocks of all the technology we have at our fingertips today. Whether you are an Apple fanatic or a devotee of Samsung, the technology that powers your device relies on the coding contained in microchips. It is the chip that’s the ticking heart of the technology. Understand the chip and you put yourself in the Fourth Industrial Revolution pound seat.

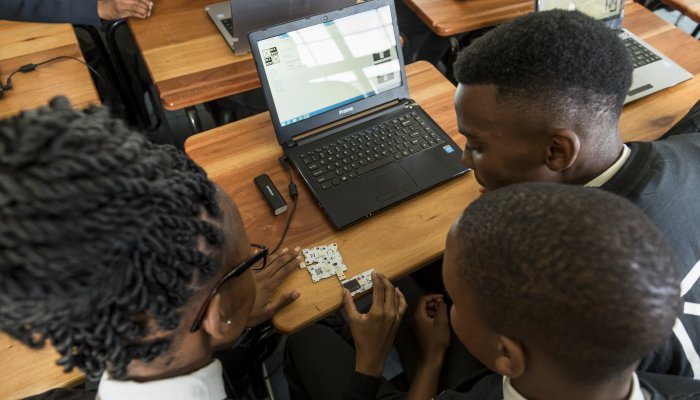

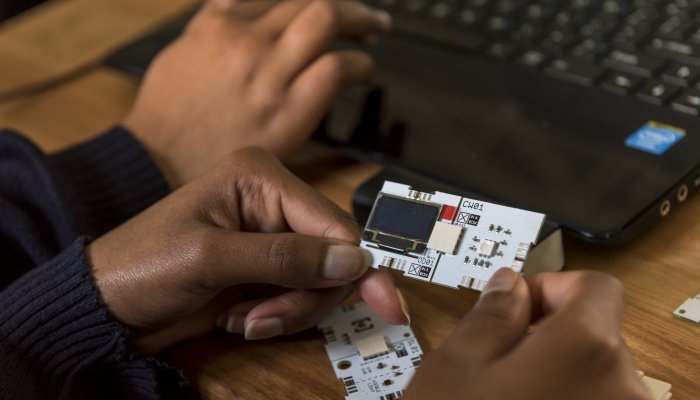

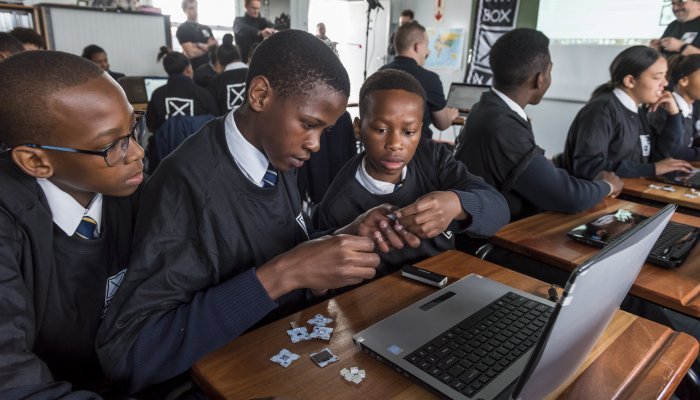

Empowering future generations to make the most of this digital world is what drives the XinaBox concept. By creating a modular xChip product that takes the fiddly slog out of assembling the physical chip, XinaBox enables users to plug xChips together and get down to the real business of programming. Its simplicity means that school children can send their creations up into space, track weather patterns or examine real-time data from the South African Antarctic base, SANEA IV. And yes, each of these milestones – and many more – have already been met by the company.

But the XinaBox story is more than its scientific credentials and education thrust; it’s a delightful combination of Dragon’s Den meets Love Island, with a twist of The Big Bang Theory thrown in for good measure. And it all started on the GIBS campus.

Setting the scene

Bjarke Gotfredsen, a Dane of South African heritage, moved to South Africa in the late 1990s. A retrenchment caused him to reassess his skill set and make the bold move of enrolling for an MBA at a new Johannesburg business school, GIBS. That was 2002. “I was one of the last pioneers,” laughs Gotfredsen from his Cape Town home office, recalling how the very first intake of GIBS MBAs graduated while he was starting his journey. “Back then there was one class and most of the faculty was international,” he recalls.

Among the guest lecturers at that time was Judi Sandrock, Anglo American’s former head of global collaboration and later head of Anglo Zimele’s Small Business Hubs initiative. The two met at GIBS and, in 2004, a friendship became a romance. Sandrock completed her GIBS MBA in 2006 and, in 2008, they married.

The potent combination of a chemical engineer with a passion for social development and a strategy whiz with an IT and communications background soon began to bubble over into a range of entrepreneurial ventures. First, they invested in a number of restaurants, but the 2008 global economic crisis put paid to that. So they established the non-profit Meta Economic Development Organisation (MEDO), which works to open doors for small, medium and large businesses.

When, in 2010, Sandrock was head-hunted to run the Branson Centre of Entrepreneurship in Johannesburg, she jumped at the idea of rolling out what was projected to be 11 centres around South Africa. But, when it became clear that expansion was not on the cards, Sandrock and Gotfredsen refocused on MEDO – only this time the exposure from the Branson Centre had opened strategic doors, including that of the then UK trade commissioner, Andy Henderson. Having signed up the British High Commission and the Royal Bafokeng as their first big MEDO clients, they hit the ground running.

A change of course

By 2014, the pair were based in Cape Town and MEDO was working with companies such as British Telecom, Microsoft and Isuzu Trucks. The Japanese car manufacturer, in particular, opened their eyes to the scale of the education deficit holding South Africa back.

“Isuzu trucks had a factory in Port Elizabeth and wanted to hire local engineers, so their focus was on bursaries,” recalls Gotfredsen. “But they couldn’t get rid of the bursaries, because the students didn’t qualify. So, they asked if we could so something earlier in the process to help students qualify for engineering bursaries.”

Applying their scientific minds to the problem, Gotfredsen and Sandrock did their homework by visiting the US state of Kentucky’s Morehead State University (MSU). Located in a modest, former coal-mining belt, Morehead was funded by NASA and had a successful programme to attract female high school learners. Gotfredsen and Sandrock were keen to replicate that thinking in South Africa.

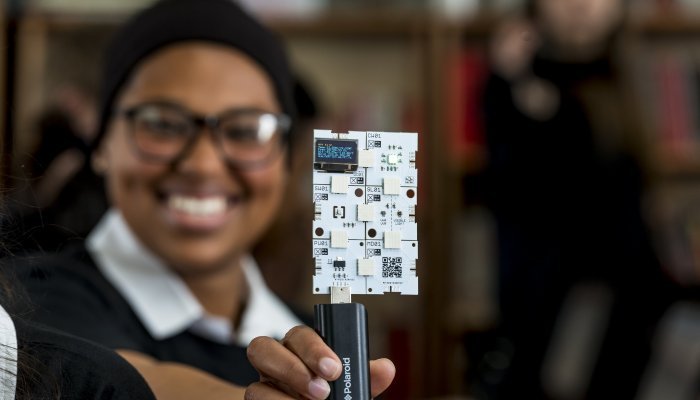

They started small, on Youth Day 2015, visiting schools in the Western Cape in a converted Isuzu truck-turned-lab to teach school children about computer chips. By early 2016, Gotfredsen had created a “Lego-style technology, where students could just click chips together and take them apart again”. They rolled out the new tech on Youth Day that year, handing each of the 153 schoolgirls who took part a five xChip rover package. “One girl, Brittany Bull, was able to analyse the driving pattern of a reference rover and program her own xChip rover in just 25 minutes. Today she is studying space science at MSU in Kentucky,” says Gotfredsen.

XinaBox was born.

A broader market

Quickly recognising the commercial applications of the product, Gotfredsen and Sandrock threw themselves into the venture. Together they came up with the name and, from the outset, they agreed that while XinaBox had a Lego approach, it was not a toy. It was a serious instrument which needed to be packaged to suit a high school learner, a university student, academic, scientist or IT professional – hence the business-like black and white branding. This was no plaything, stressed Gotfredsen, “Judi says this is from pre-school to PHD.”

They cemented the brand’s credentials by ensuring the xChips had an approval level for use in space flight and, by extension, for military, marine and hospital applications. This made the xChip an offering which could be rolled out around the world, from emerging markets looking to develop STEM skills, to developed markets hungry for an edge over competitors.

This may have seemed like a wide and ambitious market, but while attending a conference in Utah in 2016, Gotfredsen met Professor Robert Twiggs. “This was the man who invented the prolific CubeSats format [an open-source technology for satellites]. He was about 80 and I remember he stopped me mid-presentation, shook my hand and said this was the most interesting thing he had seen. We immediately hired the people we had on standby to scale up the project,” recalls Gotfredsen.

Twiggs had a particular project in mind for XinaBox: The launch of a series of satellites from the Antares rocket on its supply mission to the International Space Station (ISS). “In November 2016, Bob ordered 8,000 xChips for 100 schools in the state of Virginia, USA. We delivered that order in February 2017, and in April 2019, Judi, teachers and students went with the schools for the rocket launch of 41 satellites built using our xChips,” says Gotfredsen.

The sky’s the limit

Since then, XinaBox has been adopting a multi-pronged approach to the use of its xChips, which can interface with any number of other hardware options, from micro:bit to Raspberry Pi. “You can use our xChip across many devices, not just ours, so schools don’t have to change ecosystems, as they can just use our tech with other existing technologies,” stresses Gotfredsen.

In 2020, with the outbreak of Covid-19 and ensuant lockdowns, the value of the offering was again highlighted. “Students can do lab work at home using our tech,” says Gotfredsen. “You currently just need a computer or a laptop. No solder station, multimetere, scopes or other lab equipment is needed.”

Since mid-February 2020, an XinaBox environmental monitoring rig was outside the Antarctic’s SANEA IV base, monitoring and reporting live data to an IoT platform. And, in the same month, XinaBox’s new XK92 xChips were launched to the ISS for use in data collection efforts around CO2, climate, g-force and magnetism among a plethora of sensors.

Teachings and takeaways

Juggling such a wide range of industries and applications offers unique challenges for the team, but the wide-ranging nature of the GIBS MBA has given them a unique advantage. “It’s like oil slick knowledge. You have a broad understanding – just deep enough – to have a conversation at a board level. And we’ve found that an advantage,” says Sandrock. “In the early days we really focused on making sure we could get the business model right. Before the MBA we wouldn’t have considered business model and design, but we realised that since we are going to be manufacturing and selling hardware, we have to have economies of scale; after all it’s a numbers game.”

Today, the unofficial motto of the business is: “There is an xChip for that. How many do you want?” It keeps them focused midst an avalanche of exciting new projects and options. The rest comes down to a Great Dane, a savvy South African, the luck of the Irish and some grown-up Lego.

A US dollar business

While the potential applications for XinaBox across Africa are huge, it is the international market that has been quick to spot the potential. With Irish commercial banking expert Daniel Berman coming on board as the third co-founder in 2017, the holding company is registered in Ireland to support global trade.

“We work and quote in US dollars. We operate in US dollars. When we speak to investors, we only talk in US dollars,” says Sandrock in reference to their new round of funding. “We know we need capital to grow to the next level. We bootstrapped and Daniel brought capital into the business and now we are ready to do our first round of investment and get people in who are not family and friends.”

Currently, XinaBox counts the US as its biggest market, with top-flight academic clients such as Princeton, Georgia Tech and MIT. While there has been uptake and interest in South Africa, particularly from private schools, the “incredible interest and incredible will” shown by the Department of Basic Education and the amalgamated Higher Education, Science and Technology ministry simply isn’t backed with the necessary funds.

So, for now, the company will continue to look beyond South Africa – both in terms of production and end market. While most xChips are currently assembled in China, the black space-grade xChips are being made in South Africa. “We have all the machinery [to manufacture] here in South Africa,” says Sandrock. “We’ve had interest in building a factory here, but until we can get volumes in South Africa the numbers just aren’t viable.”