India also took a leading role in raising challenges to apartheid at the United Nations and other super-national bodies. The refusal to engage extended beyond economic spheres to sport, culture, and diplomacy.

Now, 30 years into democracy on the southern tip of Africa, the circle has turned. India and South Africa enjoy the fruits of taking a stand all those years ago. On cricket pitches around the world, this takes the form of a celebrated rivalry. Economically, the benefits take the shape of a burgeoning trade relationship.

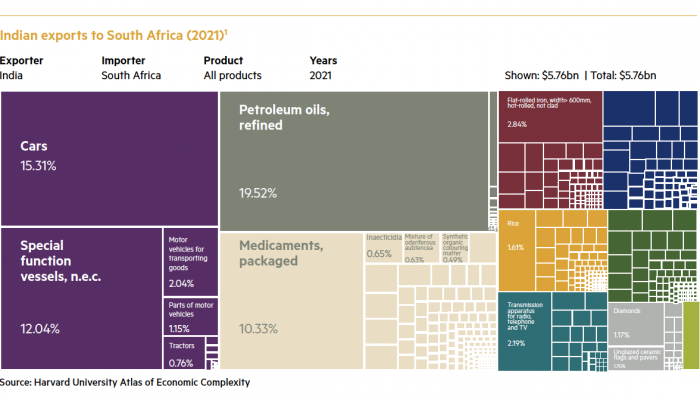

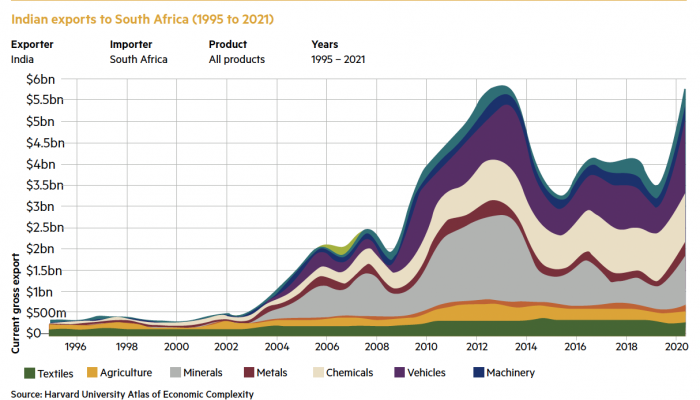

By the numbers

South Africa’s exports to India are dominated by resources. Together, gold and coal make up more than 60% of what South African companies send to India each year. The remainder is also almost exclusively unrefined products pulled out from underground – metals, petroleum products, and diamonds.

While that represents low diversity, growth has been high. From a base of zero in the wake of apartheid, South Africa’s exports to India have grown to $9.13 billion per year in 2022, according to the latest available data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC).

Build, then trade

No nation can trade successfully without a domestic economy to sustain this. With a population of 1.4 billion people and a GDP growth rate of around 7% per year, India is also the world’s fastest-growing large nation. It is redirecting itself from poor-country status towards high-middle-income status – a goal set to be achieved by 2047, according to the World Bank.

The Economist newspaper’s recent special edition on India captured the ways in which India has become a global player. “New data show private-sector confidence at its highest since 2010. Already the fifth-largest economy, it may rank third by 2027, after America and China. India’s clout is showing up in new ways. American firms have 1.5 million staff in India, more than in any other foreign country. It’s stock market is the world’s fourth-most valuable, while its aviation market ranks third. India’s purchases of Russian oil move global prices. Rising wealth means more geopolitical heft. After [Yemeni] Houthis disrupted the Suez canal, India deployed ten warships to the Middle East [in early 2024].”

That’s not all. Last year, India’s population overtook that of China to become the largest country in the world by that measure. This lead is also set to grow. An average of 86 000 babies are born each day in India, compared to 49 500 in China.

Modi’s masterclass

Trade is as much about leadership as it is about economics. On this count, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is ahead of the pack.

“Modi’s diplomacy is extraordinary,” explains GIBS Professor of Economics, Finance and Strategy Adrian Saville.

“In a world that is increasingly divided, he is a master of trade relations. Somehow, he builds relationships where so many politicians build barriers. Perhaps Modi’s most prominent antithesis is former (and maybe future) American President Donald Trump. He takes a zero-sum approach to trade. The wording that Trump uses when justifying his desires for duties on Chinese imports to the US harks back to mercantilist economics – where exporters are considered winners and importers are losers. The evidence suggests that healthy international trade is a rising tide that lifts all ships.

“Modi takes a very different tone and stance. Under his guidance, India has achieved the unlikely position of trade partner with multiple disagreeing blocs. India buys oil from Russia, sends services to the US and trades heavily with China. The personality and strategy to make this happen is enviable.”

Opportunities

Striking for its absence in India-South Africa trade data is the services industry. This is anomalous for several reasons. First, India exports a great deal of ICT services to other countries – its vast IT sector generates 7% of GDP. Second, South Africa’s economy has a large services component, particularly in finance. Third, we are in a post-Covid world of remote work, booming technology and hyper-connectivity. And finally, South Africa faces a large skills gap, which cannot be rapidly filled internally.

India exports so-called “back office” services to other countries with particular success. It has great prowess at hosting global capability centres that multinational corporations use for functions such as research and development.

“Given the way artificial intelligence and the Magnificent Seven companies are thriving, along with India’s incredible engineering talent,” says trade specialist and research associate at the GIBS Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM) Francois Fouché, “there is plenty of scope for India to export more tech services to South Africa.”

In the other direction, the starkest missing element in South Africa’s export basket to India is the lack of high value-added products. Selling resources is good. Adding manufactured and refined products to the list is better. Given the dire need to create skilled jobs in South Africa, this is an important pursuit for businesses.

Complexity calculus

This leads to the topic of complexity. The more diverse labour an economy applies to a wider variety of more complex products, the greater the potential economic development returns from trading those products. Very well, but how do we grow into this complexity?

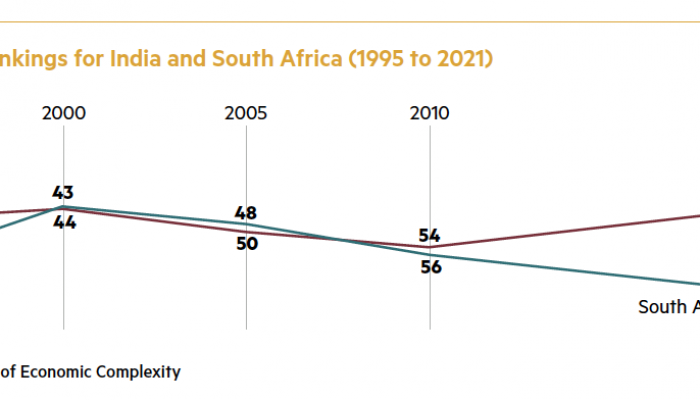

“We can turn to the data to guide an economy’s journey to greater complexity,” explains Fouché. “The Harvard Growth Lab’s Atlas of Economic Complexity is a terrific starting point. It provides its Economic Complexity Index (ECI) rankings for 133 nations, including India and South Africa.

“This is where business and policymakers need to collaborate and apply their minds to build growth strategies. We do this by answering two questions: What skills do we currently have? What products of modestly higher complexity can we expand those skills into producing efficiently?”

For a decade starting in 2000, India and South Africa tracked each other almost exactly on Harvard’s Economic Complexity Index (ECI). Each steadily lost ground in the global rankings. The decade from 2010 represents a stark contrast. India improved by 12 positions from 54th to 42nd. South Africa fell the same distance from 56th to 68th.

India and South Africa have displayed mirror opposite trajectories on one of the keystones of trade. “We should all aspire to explore more complex goods and services,” explains Fouché. "Selling iron ore, for example, is a good thing. But even better is to sell products that we have manufactured from this ore.”

This stands to reason. Creating more complex products requires more diverse labour and value-add. This means more jobs and the premium that comes with more specialised products.

“My favourite example of the contrast in complexity lies in the Mahindra case study,” continues Fouché. “I don’t know if I had heard of Mahindra in 2010. However, earlier this year the Mahindra Scorpio-N drove away with SA Car of the Year in the Adventure SUV category. The brand is now up there with the likes of the hugely successful Japanese and South Korean ones we have known and loved for many times longer than we have Mahindra. That is incredible for a product as complex as a car, where consumers have such strong brand affinity.”

Several much-lamented headwinds are likely drivers of South Africa’s decline in complexity. The inability to produce sufficient electricity, resulting in widespread load-shedding, dampens productivity. Skilled labour is also departing South African shores via emigration and a disastrous education system is failing to produce skilled youngsters of the sort that drive a modern economy.

Room for growth

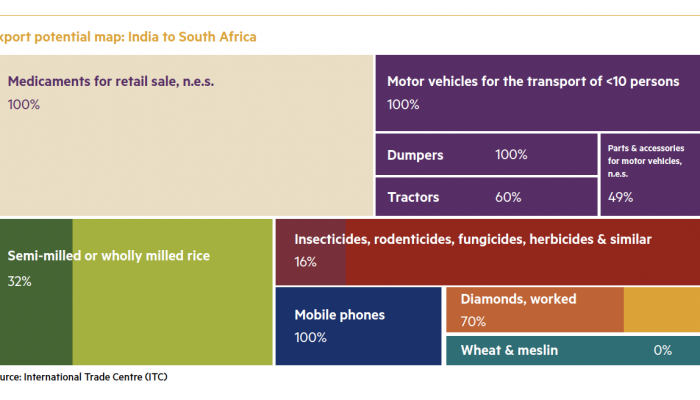

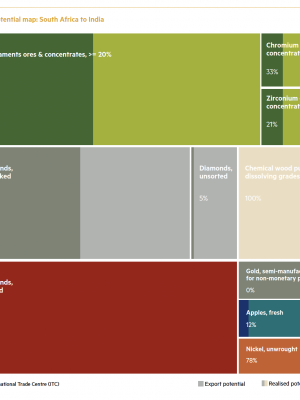

The International Trade Centre (ITC) analyses bilateral trade to seek out opportunities to grow trade between nations. Its widely used tool takes into account inputs including tariffs, distances, sea access, trade relations, and market share to determine the products and services a nation can most productively expand into and export to a chosen buyer nation. This provides policymakers with strong guidance on where to apply incentives.

Applied to India’s export basket to South Africa, the ITC finds the greatest unmet potential in semi-milled and wholly milled rice. According to its calculations, just 32% of this potential is being realised, leaving room for an additional $205 million in exports per year.

Applying this calculus to South Africa’s exports to India, the ITC finds that the greatest bang for buck lies in additional exports of diamonds. Its calculations suggest additional room for $627 million in exports of worked diamonds per annum, given a total export potential that is currently just 7% met.

“The power of this knowledge should not be underestimated,” argues Fouché. “Policymakers have a daunting task. They are under constant pressure to help and hinder all manner of industries. It can be hard to decide where to start. Armed with tools like this, they have a fighting chance at developing policies to enable industries at the right time.”

Shortening the distance

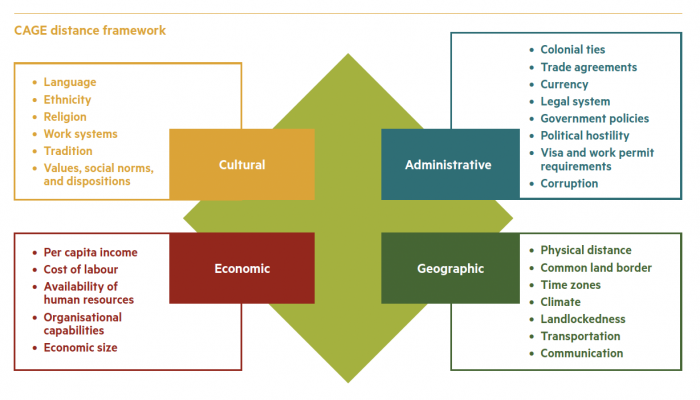

The distance of some 8 000km between India and South Africa is fixed. But that is not the only type of ‘distance’ between us. IESE’s Prof. Pankaj Ghemawat outlines four types of distance between nations: cultural, administrative, geographic and economic, making up his ‘CAGE’ framework. Each has an impact on how easy it is to trade. Some factors are just as fixed as physical distance. However, others are malleable.

Culturally, India and South Africa are diverse and nuanced places. There may be as many differences as there are similarities between the two. One name in particular cements the closeness in this bilateral relationship: Mahatma Gandhi. A shared struggle icon, revered in both nations, may seem removed from international trade in 2024. But the impact is real, certainly in political and diplomatic circles. Many South African political leaders in place today grew up with stories of India’s Gandhi as a stalwart of the resistance movement. That sort of affinity is enduring.

Diplomatic relations are sound and growing. During recent celebrations of 30 years since the end of apartheid and the resultant end of India’s complete embargo, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa engaged warmly and publicly, including at the 15th Brics Summit in South Africa.

These sorts of public displays are never by accident. The two heads of state sent a clear signal to diplomats and businesses alike that their respective nations are good friends and open to more trade.

The economic pillar of CAGE operates slightly differently from the other three. Here we aren’t necessarily looking for closeness. The key is synergy. That frequently equates to large differences that complement each other. This has been inherent in the analysis above – trade works where one nation has something another one does not, i.e., trade complementarity exists.

The differences in population size provide South African businesses with obvious incentives to trade with India. Once you are established among South Africa’s 60 million consumers, 1.4 billion Indians represent a daunting but enticing opportunity. The same applies to India’s workforce. Approximately one billion Indians are of working age, labour rates are relatively low and education in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects is good and improving.

Shifting view to the other direction, India can benefit from South Africa’s resource richness. While India has grown rapidly as a services economy, it has not industrialised like China and Vietnam. These nations have boomed by manufacturing and exporting.

Modi appears to have realised this. A state-run incentive scheme to promote manufacturing evidences this. However, far more is needed. The playbook written by Asia’s modern success stories suggests that India needs many more factories buzzing with skilled workers and automation. That will make it more resource-hungry.

It is three-quarters of a century since political schism moved India and South Africa so far apart. Today, new dispensations, modern technology, and the benefits of trade have brought the two closer than ever before. Economic synergies, cultural bonds, and more suggest plenty of room for the relationship to flourish further.

By Ian Macleod, GIBS Centre for African Management and Markets (CAMM)