It’s 10.30 am, the sun an angry eye in the sky, as I watch an elephantine Gauguin hold a paintbrush in his trunk, select a vivid shade of orange, and apply pigment to paper. He paints a flower with petals, leaves, and stamens.

Lifting his back leg in concentration, he completes two more blossoms. With finesse he then signs his name – Ora Chai – beneath his masterpiece that will be sold to raise money for his sanctuary at the Maesa Elephant Camp.

It takes just three months to teach a pachyderm to paint. Their sophisticated trunks contain between 50 000 and 150 000 muscles – experts still cannot agree on the number – with prehensile, finger-like appendages at the tip that aid in flicking a coin, stabilising a log, or turning out an intricate still-life.

Ever since the Thai logging industries laid them off in 1989, Asian elephants have had to entertain tourists to earn their keep as industrial greed destroys their habitat. Even so, their population declines apace with fewer than 3 000 left in the country.

The precarious future of these gentle giants makes spending time with them all the more precious. Living is easy with eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see. Strawberry Fields marinates my brain as my 5.15 alarm brings me back to 3D reality.

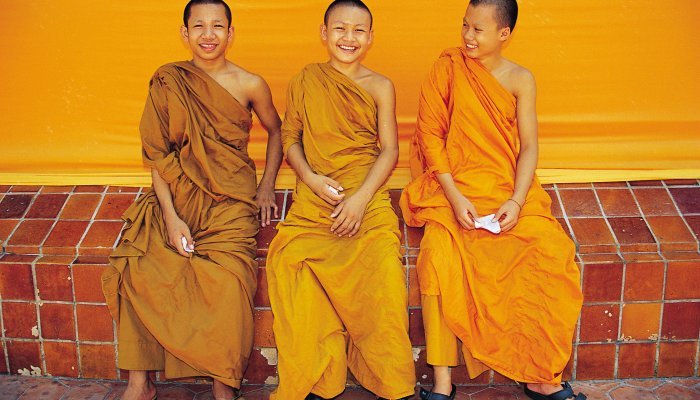

I had signed up to feed the Buddhist monks. They, I reflect, would have been up meditating for two hours already. Lofty thoughts or contemplation of the quality of the snacks to come, well who could say? Buddha prescribed some rigorous tenets for living, all in return for … nothing. Then again, nothing is real so nothing to get hung about. Riiight.

By dawn people had prayerfully lined the road with their food offerings. Thai people believe the way to heaven is via the hem of a monk’s robe, so the snacks looked good. Hawkers flogged birds in tiny cages you could buy to set free for good luck. The hapless creatures would then be trapped again and resold. The truly devout held up placards exhorting abstinence from alcohol and smoking. Suddenly seventh century sacred chants filled the air and a long orange ribbon of monks appeared. Caught up in the energy of sound, I felt light-headed. Hunger pangs gnawed but I resisted the temptation to purloin a drumstick. Buddha might be watching. You never know.

After an hour of the chanting, the monks – from seven years upwards – went around collecting the food in steel bowls.

The following day dawned on the lunar New Year, aka Songkran Festival. Traditionally, temple goers sprinkled scented water over each other to wash away bad thoughts but these days people drench each other on the streets. Tourists and police officials alike are considered fair game.

As one impudent lad hurled a bucket of water in my direction with distressingly good aim, I told myself my sins had been cleansed for another year, but it was cold comfort indeed.